A Love Supreme: Imagining my father’s madness

by Natasha Williams

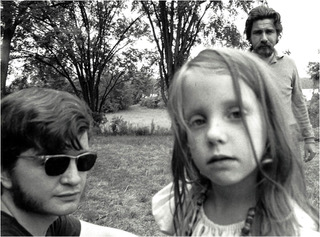

photo collection of the author

The kitchen was thick with cigarette smoke and A Love Supreme, his favorite Coltrane. I danced with scarves wrapped around my undersized torso, one tied gypsy-like around my head. Dime-store clip earrings dangled at my neck. I twirled to his lap, where he slumped over his coffee cup at the dining room table, and pulled on his hand to join me. Anchored to his chair by something weightier than our life could contain, he chuckled, looking into his cup, waiting for the “holy” calling only he could hear. I returned to spinning on the linoleum in the small living room where the beige walls were sticky and darkened to a golden yellow from the residue of a family of chain smokers. The cymbal brushed, the piano pounded, the saxophone wailed, Dad exhaled, and I tried dervish-like to get him look up and smile.

Since my mother long ago renounced living with “the Messiah,” my father had to drive across the Verrazano Bridge every Friday. His coming to pick me up was one of the ways I knew he loved me. Each car ride felt like a new beginning, surrounded by other commuters, people headed home or to the beach for the weekend, part of that great exodus from the boroughs to Long Island.

“Everyone and their mother are on the expressway tonight,” I said triumphantly as we sat in that dense traffic. Our windows open to the smell of the ocean and exhaust.

“Yeah, Baby,” he smiled.

We were headed to Hempstead, Long Island, to the house where my father grew up. A quiet, working-class neighborhood where newspapers were tossed on the driveway and stray grass grew long in the uneven cement sidewalk. The house was a small, white, four-bedroom Cape-style home with clapboard siding and a front porch Grandpa closed in years before. It was an unremarkable house improved by a family who had hoped to raise its prospects. My father’s siblings, four total, each five years apart, had worn a pathway into the green linoleum floors with their unsupervised play over the decades. Now Grandma lived next door, worked the night shift at the hospital, and helped Dad with his affairs.

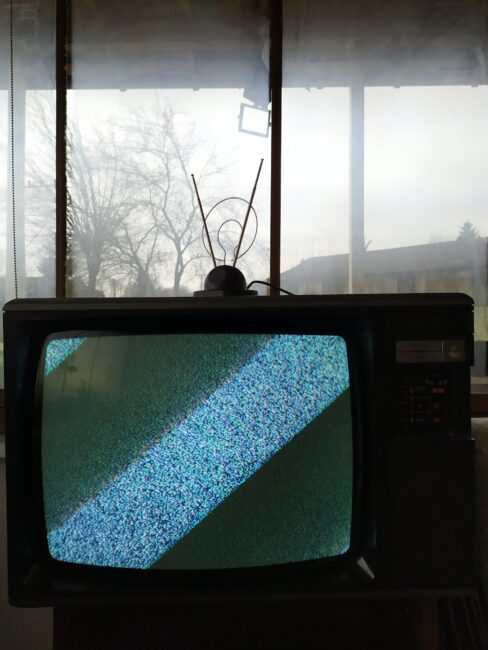

Late into the night I found companionship in the magic of television. With a liverwurst sandwich on a small Melmac plate on my lap, I watched Pillow Talk and Gidget Goes to Rome. Doris Day and Cindy Carol danced and sang in tailored dress suits with chivalrous men in dapper outfits and honey-sweet voices. My father resembled those men in his dark handsome features and his schemes for success, but he never could hold down a job: his sole steady income from Social Security Disability. With his degree in history and teacher certification, he had occasional substitute “gigs,” as he called them, in a social studies classroom, usually in schools with the toughest of tough students.

Dad often slept well into the afternoon. Like a lion in his sun-drenched bed, his snores rumbled from the back room. I made up songs about a princess with many names, Christina Maria Antoinette, and make-believe friends. My dress-up clothes heaped like personas on the floor.

“Dad, it’s time to get up.” I went to him and rolled him awake with a gentle back and forth on his large sunburned back.

“It’s time to get up, Dad,”

“Peel my back baby, and then I’ll get up,” he mumbled, asleep on his stomach, his face mashed into the pillow. I sat on his back and lifted the dead skin in sheets from his sun burn. The past weekend at Jones Beach the tide had been just right for hundreds of jellyfish to float up to the surface and litter the sand all around us.

“Look at them all! Let’s clear out an area to swim in,” I had said.

Lean and handsome, my father marched to the shoreline and swiped at his thick dark hair in consideration.

“We’ll bury them in holes!” he directed, and an unspoken contract for eradicating the threat was hatched. I dug the first hole with driftwood, and we pulled the transparent moon disks out of the ocean.

We dragged each along the sand into their own pit. I pulverized each jellyfish in its sandy dark burial ground just to be sure. I felt powerful as I transformed their perfect roundness into something resembling sandy mashed brains. Each creature covered with sand, marked with an X, and a stick so we could identify the grave. Then on to the next. Together we were ridding the world of one of God’s creations that got in our way; one of God’s mistakes.

After we killed maybe twenty jellyfish, we found relief from the heat, dipping calmly in the roiling waves. Me in Dad’s arms, protected from the wild surf. We bobbed up and down in the ocean’s push and pull. Although there was no one to document my childhood alone with my father, no iconic pictures of a father with his daughter at the beach, it was Dad who held me securely above the undertow.

We lay in the sun till our skin burned red and the sun started to set. Then we gathered up our towels, and I followed his steady step, through the sand and over the burning pavement. Dad’s sandals slapped like fins, and I leaned into his hand to keep up. Our steps cut a consistent, comforting rhythm, flap, flap, and my catch-up skip, as if together we made a heartbeat.

His skin smelled like home, a tactile reminder of the genes we shared. The freckles on my nose and cheeks reflected the ones splattered on the shoulders and arms of Dad’s people. Not like my hippie mother—a German, Dutch, and English third-generation immigrant who hated her family. Her unblemished skin and exacting brown eyes, which grew pellet-like when she was angry, repelled me. I preferred the Irish I got from Dad’s side.

The afternoon sunlight streamed in through the wooden venetian blinds. Finally, he sat upright on the edge of the bed with his feet planted in front of him like two legs of a tripod yawning a concert of calls to our pride of two. “Come on, Dad,” I said sitting on the bed next to him, leaning into the side of his belly, “We need to go the store.”

“Ok, Baby, let me have a cup of coffee first.” He stalled. It would be hours before we set foot outside. If his check had just come, we would go to the local supermarket and splurge. Dad loved pickled herring and steak and even caviar if he was feeling particularly high-minded. I went for the sugared cereals and popsicles—food my mother would never allow. “Get what you want, we’re having a party!” He announced, which meant he would invite a friend who usually wouldn’t come.

When my father said “anything you want,” he meant it, including the taller-than-me stuffed giraffe I fell in love with in the toy aisle.

“Yeah, put it in!” he encouraged. “We’ll see if we can swing it.”

Our packed cart with meat and leafy greens, Lucky Charms, and a limitless supply of popsicles for late-night TV watching was testament to the power of his love. We unloaded our indulgences at the register hoping we had enough money. Counting out his last dollars and the change in his pocket to the last nickel and dime, we strutted out with the prize giraffe in my arms and bags of groceries in Dad’s.

When we were having a “party,” the friend he called most often was Freddie, the local pot dealer. “Come on over, I’ve got steak, and we’ll smoke a joint,” he’d say. Sometimes Freddie would come, but mostly we were a party of two.

He cooked collard greens with garlic and sizzled steak in a cast iron pan and served us with the gusto reserved for good food. It was at my father’s that I understood home was the place you just had to show up at to be fed and loved. Nothing more.

“Some steak, huh, Tash?”

“It’s so good, Dad.”

“Too bad we don’t have cheesecake for dessert.”

“We could get some.”

“Yeah, maybe, baby,” he said as if the cake was yet another thing he would have to forgo in life. He sat smoking at the table, quietly shouldering the disappointment about the company that didn’t show. Lethargic from the pills meant to still the voices in his head: voices that promised he was the Messiah but repeatedly failed to deliver the apostles.

So much about our life together was like a silent prayer: waiting for company, imagining our purpose, holding what no one could explain.

Whenever he could, Dad sent checks to foster children in Africa, moved by photos of their bloated bellies and crusted mouths, which lay in piles on the table. He worried about the bags of discarded food thrown into dumpsters every night from my grandfather’s catering job. He yelled at Grandpa about how he himself had rummaged in dumpsters in the city and handed out the food restaurants threw away. “Do you know how many people all that food could feed?” he shouted, as if Grandpa were behind all the waste and starvation.

With a mix of altruism and righteousness, he wanted to save the world, but at the very least he would share what he had. “Sit down, let me get you something to eat!” he’d insist with any visitor who showed up. He felt compelled to feed the poor and even imagined he could perform miracles. When drunk with his own power, he told our waitress he could make her immortal.

When his mania morphed into paranoia, he was convinced he had the power to kill even his friends with his eyes if he wasn’t careful. Transformed into an arrogant prophet, he demanded of me, “You know I’m the Son of God, my child? And I have a message to impart.” I was his ally who needed protection from his enemies, even when his delusions made everyone else in the family a threat. But his trust in me left me lonely inside. I wasn’t what he thought, not a disciple or even a believer in the stories he told about himself and my doubt hardened something inside me.

At the end of the weekend, in the hours before the drive back to Mom’s, we watched Sunday night opera. I cried, because the arias were so sad and beautiful and because I had to leave him alone again with the messages in his head, that mission no one understood.

“What’s wrong, Baby?” he asked, calling me over to his lap.

“I’m just going to miss you,” I said, tears streaming down my face.

I leaned into his chest and oversized belly and breathed in the familiar bittersweet smell of tobacco and coffee. I wanted desperately to enter the jungle of his mind, to join him with my prized giraffe on his adventure. I knew when I returned to my mother, he would disappear again for months, endlessly walking the city streets with God’s voice clouding his head.

Natasha Williams has worked as an adjunct biology professor at SUNY Ulster in the Hudson Valley of New York and a consultant for the International Public School Network coaching science teachers. In summer of 2020, she accepted a spot with the Bread Loaf School of English, and this summer of 2023 will be at Bread Loaf Writers Conference. She has taken classes at Grub Street, Fine Arts Work Center, Sarah Lawrence, and Sacket Street Writers. Essays and Excerpts of her memoir, The PARTS OF HIM I KEPT, have been published in the Bread Loaf Journal, Read650, Change Seven, Memoir Magazine, Open Minds Quarterly and South Dakota Review.