Two Poems by Pietro Federico "New Jersey" and "West Virginia" Translated From the by Italian John Poch

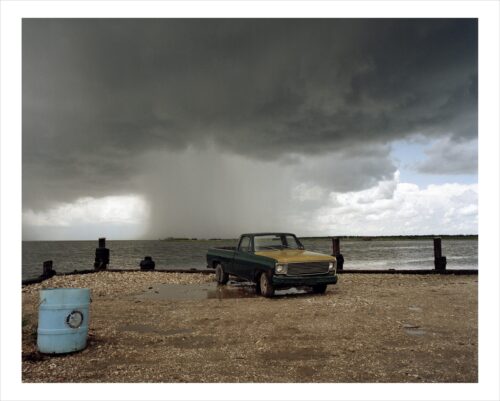

photos by Giovanni Chiaramonte

WEST VIRGINIA

The shack is like a bone half-buried

in the forest of West Virginia.

The two of them live there married.

How black the pigment of their skin

and the hollows of their mouths.

The wrinkles at the corners of their eyes

radiate like wind-struck tears.

Their clarity the only thing clear.

Angels. If they look at you it appears

their souls are looking at you,

and that their souls overflow,

and that these bodies of theirs are only shadow.

I speak in present tense, but they found them

on the shoulder of the highway

on the thirtieth of December.

They had no telephone.

She was feeling bad.

He lifted her onto his back,

her heels held fast to his stomach.

He fell after just a hundred meters,

out in the spinning gusts of icy air

circling tighter with every breath.

Maybe he sang her a song.

And they stayed there,

black in the snow-blind weather

as in the seconds when one drifts to sleep

where things get mixed together

and all begins again.

I had icy tears running down my face,

fire in my eyes.

Maybe it was only the rigid violence of my weeping

by which she, her body empty now,

was scratching my chin with her wedding ring.

Perhaps it was the rough hour of the scriptures

where a foot slips,

where love is time, miseries, fears,

and into peace one can only collapse.

As into a trap.

Where the white lion of winter kisses

both my failing body that holds her own

and her face as black as a lamb.

WEST VIRGINIA

La baracca è un osso mal sepolto dentro

la foresta del West Virginia.

In essa vivono lui e lei.

Così nero il pigmento della pelle

e il cavo delle loro bocche.

Le rughe agli angoli degli occhi

si irraggiano come lacrime controvento.

Chiare l’unica cosa chiara.

Angeli. Se ti guardano sembra

che ti guardino le loro anime

e che le anime trabocchino

e che il loro corpo sia solo un’ombra.

Parlo al presente ma li trovarono

sul bordo della statale

il trenta dicembre.

Non avevano telefono.

Lei si era sentita male.

Lui l’aveva caricata sulla schiena

i calcagni di lei conficcati nello stomaco.

Cadde dopo cento metri appena

nelle spire dell’aria glaciale

più strette a ogni respiro

forse cantandole una cantilena.

E restarono là

neri nel candore micidiale della tormenta

nel secondo in cui ci si addormenta

in cui le cose si confondono

e sembra di tornare alla partenza.

Avevo lacrime ghiacciate sulle guance

negli occhi fuoco.

Era forse solo il pianto per la rigida violenza

con cui lei il suo corpo ormai vuoto

mi graffiava il mento con l’anello.

Forse l’aspra ora delle scritture

dove metti un piede in fallo

dove amore è tempo miserie paure

e nella pace si può soltanto cadere.

Come in un tranello.

Dove il leone bianco dell’inverno sta baciando

il mio corpo infermo che la tiene

e il suo volto nero di agnello.

NEW JERSEY

A Vietnam veteran – 1975, Newark Airport, New York, 11 pm

To take a mattock and dig a trench

in the training camp behind the tents

or to leave on a plane doesn’t make any difference.

But I start to find out the difference

when we disembark the cargo plane

and I see leaving in the opposite direction a platoon of coffins.

I almost forget to keep walking.

And so I go to war:

reconnaissance and cover,

almost always my belly on the ground,

and fear is just another arrow in my quiver.

Mama put in my pocket a prayer to St. Joseph,

a prayer to pray when all turns south.

For this my sergeant mocks me all the time.

Already on his third tour,

his skin is thick like leather on a drum,

with a good heart, a godless soul

and an iron mind forged on the front lines.

Sonofabitch, this just

can’t be real: bite the dust

on my mother’s birthday?

Nineteen seventy-one, the seventeenth of November

we’re forced to fall back or none

comes out alive, not one.

Thousands of Charlies crash from the north in waves.

From a football field away, we can feel the air blaze,

reaching through the foliage in gusts,

the heat of hatred without mercy.

Someone must provide the cover, so I volunteer.

The sergeant crawls up beside me,

that skin on his face like stretched leather:

Do you have that prayer?

I land in Newark, eleven at night.

It’s pouring like in Nam, and I want nothing more

than to hug my father

and to tell my mother about her prayer.

I’m telling you all this not because I sense

that my peace is more truly

real than your life among incense

because, to be frank,

you will not find in me a trace of peace.

While I sing “O say can you see…”

and salute our banner

allow me to have the manners,

the universal peace that you spit in my face,

and to confuse it with my hate, my inhuman past,

with that land on which I crept

among the piss, the tears I wept,

with this rain that does not wash the skin, and the bars

of white do not erase

the blood from the stripes

assailing that corner of stars.

NEW JERSEY

Un reduce del Vietnam – Aeroporto di Newark, New York, 23:00

Prendere una zappa e scavare una trincea

nel campo addestramento dietro la caserma

o salire su un aereo è indifferente.

La differenza comincio a vederla

quando scendiamo dal cargo

e in senso opposto vedo salire un plotone di bare.

Quasi mi scordo di continuare a camminare.

E così vado in guerra

ricognizione e copertura

quasi sempre pancia a terra

la paura è solo un’altra arma nel mio arsenale.

Mamma mi ha messo nella tasca una preghiera a San Giuseppe

da pregare ogni volta che butta male

e il mio sergente ci ride sopra continuamente

è già al suo terzo tour

ha la pellaccia resistente come cuoio di tamburo

il cuore buono l’anima atea

e una mente ferrea da prima linea.

Boia ladra non ci credo

vuoi vedere che tiro le cuoia

il compleanno di mia madre?

Il diciassette novembre del millenovecentosettantuno

siamo costretti a ripiegare

o non ne esce vivo nessuno.

Migliaia di Charlie si schiantano da nord a ondate

da cento metri avanti sentiamo lo spostamento d’aria

ci arriva in faccia dal fogliame a zaffate

l’afa di un odio senza perdono.

La ritirata va coperta e mi offro volontario.

Il sergente mi striscia affianco

sulla faccia quella pelle tesa come cuoio.

Ce l’hai con te quella preghiera?

Atterro a New Ark alle undici di sera.

Diluvia come in Nam non voglio altro

che abbracciare mio padre

dire a mia madre della sua preghiera.

Ti dico tutto questo non perché io pensi

che la mia pace sia più vera

della pace che tu vivi tra i tuoi incensi

perché ad essere sincero

di pace in me non è rimasta traccia.

Mentre canto l’inno

saluto militare alla bandiera con la mano

permettimi di accogliere

la pace universale che mi sputi sulla faccia

e di confonderla al mio odio al mio passato disumano

a questa terra su cui striscio

tra piscio e lacrime

a questa pioggia che non lava la pelle

come il bianco non leva

il sangue dalle strisce

che assediano quell’angolo di stelle.

PIETRO FEDERICO was born in Bologna, Italy in 1980, and currently lives in Rome. Writer, copywriter, story editor and translator. His poetry books include “Non nulla” (2003, Ibiskos Editore, Empoli), winner of the prize “Il Fiore” Pistoia 2003; “Mare Aperto” (Nino Aragno Editore, Turin, 2015), winner of the Subiaco Award 2015 and Ceppo Award 2017; and “La maggioranza delle stelle – Canto Americano” (Edizioni Ensemble, Rome, 2020). His translations include “Le storie più mute” by Katherine Larson (Edizioni Interlinea), “La ballata del carcere di Reading” by Oscar Wilde (Giuliano Ladolfi Editore), and “Poems” by Martha Serpas (in Testo a fronte published by Marcos y Marcos).

PIETRO FEDERICO was born in Bologna, Italy in 1980, and currently lives in Rome. Writer, copywriter, story editor and translator. His poetry books include “Non nulla” (2003, Ibiskos Editore, Empoli), winner of the prize “Il Fiore” Pistoia 2003; “Mare Aperto” (Nino Aragno Editore, Turin, 2015), winner of the Subiaco Award 2015 and Ceppo Award 2017; and “La maggioranza delle stelle – Canto Americano” (Edizioni Ensemble, Rome, 2020). His translations include “Le storie più mute” by Katherine Larson (Edizioni Interlinea), “La ballata del carcere di Reading” by Oscar Wilde (Giuliano Ladolfi Editore), and “Poems” by Martha Serpas (in Testo a fronte published by Marcos y Marcos).

JOHN POCH’s poems and translations have appeared in Poetry, Paris Review, Agni, and many other magazines. His most recent book is Texases (WordFarm 2019). He is the series editor of the Vassar Miller Poetry Prize, and he recently edited the collection, Gracious: Poems from the 21st Century South (TTU Press 2020). His first book of criticism, God’s Poems: The Beauty of Poetry and the Christian Imagination is recently out with St. Augustine’s Press.

JOHN POCH’s poems and translations have appeared in Poetry, Paris Review, Agni, and many other magazines. His most recent book is Texases (WordFarm 2019). He is the series editor of the Vassar Miller Poetry Prize, and he recently edited the collection, Gracious: Poems from the 21st Century South (TTU Press 2020). His first book of criticism, God’s Poems: The Beauty of Poetry and the Christian Imagination is recently out with St. Augustine’s Press.

GIOVANNI CHIARAMONTE was born in Varese, Italy in 1948 to Sicilian parents. He began taking photographs at the end of the 1960s, moving toward the figurative and away from the abstract. His work focsues on the relationship between place and human’s identity. Since 1974 he has exhibited worldwide, inclduing at the Triennale of Milan in 2000, 2009, and 2011 and at the Biennale of Venice in 1992, 1993, 1997, 2004, and 2013. In 2010, his work was exhibited at “Hidden in Perspective” at the Expo in Shangai. He founded and directed collections of photography for different Italian publishers. He teaches the Theory and History of Photography at the Free University IULM and at NABA Academy in Milan.

GIOVANNI CHIARAMONTE was born in Varese, Italy in 1948 to Sicilian parents. He began taking photographs at the end of the 1960s, moving toward the figurative and away from the abstract. His work focsues on the relationship between place and human’s identity. Since 1974 he has exhibited worldwide, inclduing at the Triennale of Milan in 2000, 2009, and 2011 and at the Biennale of Venice in 1992, 1993, 1997, 2004, and 2013. In 2010, his work was exhibited at “Hidden in Perspective” at the Expo in Shangai. He founded and directed collections of photography for different Italian publishers. He teaches the Theory and History of Photography at the Free University IULM and at NABA Academy in Milan.