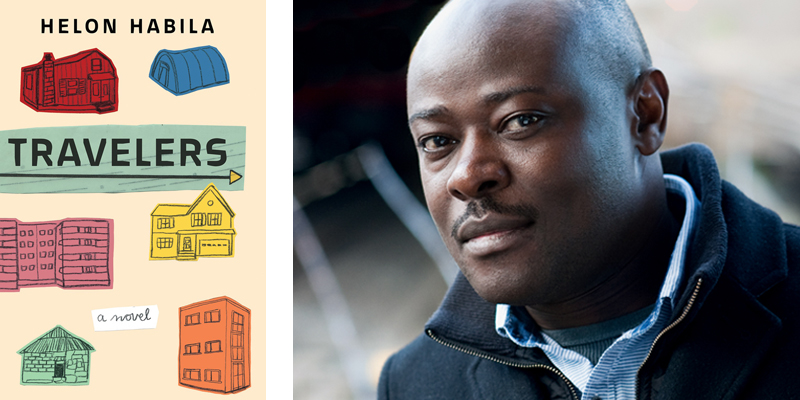

“Interview with Helon Habila” by LaVonne Roberts

Helon Habila‘s fourth novel, Travelers, is a novel about African Diaspora in Europe. Told through a series of interlinking narratives, an unnamed Nigerian scholar’s experiences with migrants in transit, the real question Travelers asks is: what is home? Originally from Nigeria, Habila lives and teaches creative writing in the US at George Mason University and is the author of Waiting for an Angel, Measuring Time, Oil on Water, and a nonfiction book, The Chibok Girls.

LaVonne Roberts: One of the many things I loved about your book is how you opened my eyes to Africa. Your book shamed me into reading more and asking questions. It occurred to me – that is the point of great literature – to incite curiosity and awareness. Was that part of your goal—to engage your readers in different countries where refugees are feeing and the European counties reactions?

Helon Habila: My primary purpose in writing Travelers was simply to tell a story, the story of people traveling, not all of them refugees. Some are traveling for other personal reasons. Of course, one of the main themes in the book is about exile and the refugee experience, but I was hoping my illustration of the general human condition would be more primary than just the refugee experience. I am aware that most Western readers wouldn’t know the countries referenced in the book, but that notwithstanding, they’ll still be able to enjoy the book because, in the end it is just about people like them trying to seek a new home elsewhere when their native home fails them.

Your character, the dissident Zambian poet in exile in London, who, drunk on fame, portrayed Africa as “one huge Gulag archipelago” to Western liberals. What has been your experience? Have you seen other artists sell out “their” Africa for some sort of gain?

Habila: In writing about the Zambian poet in the book, I was simply exploring one aspect of the migrant or exile psychology, the one where the exile turns his back totally on his home country and doesn’t even want to hear it mentioned. Here the poet doesn’t want to hear about Zambia because of his imprisonment and persecution by the Zambian government. But it is a common phenomenon among most migrants to turn their back on their home country and want nothing to do with it. The other extreme of such behavior is those who pine after their home country and refuse to fit into their new home–they suffer from incurable nostalgia and guilt, a sort of trauma from which it is sometimes impossible to recover. Edward Said talks about this at length in his brilliant essay, Reflections on Exile.

Was it important for you to convey your version of Africa?

Habila: No, I don’t see myself as a spokesperson for Africa. And, like you pointed out

earlier, Africa is actually a very big place, not one country. I am simply a writer trying to

write about people and about themes that interest me.

Do you consider parts of your novel to be an autobiographical novel?

Habila: Most of the characters in the book are real people who I met when I was in Berlin in 2013/2014. In that sense it is biographical; it is also tangentially autobiographical because I drew on my own experience of Europe to write the book. All works of fiction have some basis in real life. However, this is not an auto-fictional work, there is a lot of defamiliarization and distancing of setting and material for practical purposes, that is in order to make the story work and to meet the requirements of plot and theme.

Did you write Travelers as fiction to protect some of the stories/characters?

Habila: Not so much to protect the actual stories and characters but more to make the stories work. I am conscious that as a writer one of my important requirements is to make my story interesting, to do so I often have to change what is real and possible to what is fictional and probable.

As someone who lives outside your country of origin, do you think it’s ever possible to be at home in your life? Do you identify with one place more than another?

Habila: I think it is important for everyone to experience other cultures and other places other than where he or she was born. It widens our sympathies and our understanding of people and life in general–this is especially important for an artist. As a traveler, an outsider, one is freer to observe and learn, and to be less subjective in ones judgement.

We learn to see better when we travel. I find it harder and harder to decide where I identify with more than another. My home country, Nigeria, made me who I am, it formed my politics and my early memories; America makes me appreciate the importance of diversity and tolerance and hard work and justice; Europe taught me how to enjoy life with friends and to appreciate art. Each one of them is like home to me. I cant choose one over the others, but perhaps I will always be partial to Nigeria because it is the first place I ever knew so everything else will have to be compared to Nigeria.

In a Guardian interview you talk about sometimes wanting to you your mother that you feel “guilty living so far away, from her, from home. To explain that writers often had to distance themselves from home in order to be able to create a more perfect home in their books, and that for me there could never be a return, only visits.” You add that your father-in-law was right when he said we must make our home wherever we happen to be. To any person in search of a place called home—do you have any advice?

Habila: There can be more than one home.

You teach writing—any advice for other students studying writing?

Habila: Writing is hard. Don’t seek to master it in the time it takes you to get your MFA—learning continues after you graduate. Each book will be a new learning experience. Sometimes it takes a whole lifetime to master the skill of writing, but it is worth it.

*

LAVONNE ROBERTS is the author of award-winning short stories, personal essays, and poetry. Her writing has appeared in Litro Magazine, The Rio Review, The Blue Mountain Review, The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature, Waco Arts Fest Anthology of poetry, and When Women Waken anthology, among other publications. She currently resides in New York City, where she is completing an MFA at The New School and a memoir called HOME. She is the founder of WRITE ON!, which partners with provides literature and free ongoing community based creative writing workshops for marginalized populations like female victims of violence and adults who are experiencing homelessness.

© LIT Magazine 2019