Kristen Roupenian on Writing and Getting Your MFA, Interviewed by LaVonne Roberts

Kristen Roupenian will be interviewed on LIVE with LIT as a part of LIT’s Commencement 2020 this Tuesday, May 19th at 7pm. Join here.

*

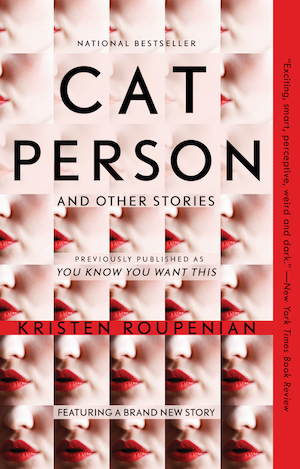

“Cat Person” was published by The New Yorker on Monday, December 4th, 2017, and by that Friday, it was the most-read piece of fiction of all time on the magazine’s website. It earned its author – who was then completing a writing fellowship in Ann Arbor, Michigan – global fame, quickly followed by a seven-figure, two-book deal.

*

I read 4.5 million views. Is that number correct?

Maybe! It’s a number I’ve seen before, but I don’t have any behind the scenes access.

Asking what makes a story infectious is like asking what is it about an essay or short story that encapsulates what it is to survive in a broken world. We all know that the best kind of writing is the kind that uses strong, vibrant language that immediately draws you in and makes you want to read more. In your opinion, how much of the winning formula is craft versus a timely theme versus a fresh new spin on storytelling?

With regards to a story being ‘infectious,’ (quite a word!) in the sense of becoming part of a much larger dialogue, I think ‘timely theme’ matters most, in the sense that it has to be a piece that people not only enjoy but want to talk about. ‘I like this’ or even ‘This had a powerful effect on me’ probably isn’t enough to get a story trending on Twitter. Most of the stories and articles I see becoming a flashpoint in that way are hooking into a larger ongoing conversation; they’re serving as a platform for people to talk about something beyond the story itself. That said, I think there’s a certain element of randomness involved, and I’m not sure this is something it’s ever worth consciously aiming for. These cultural conversations move so fast, and so unpredictably, that if you set out trying to write a story that captures that energy, you’ll inevitably be playing catch up.

Much better, I think, is just to remain open and attentive to what’s going on in the world, and to allow that awareness to filter into your story naturally, trusting that if you’re writing about what feels immediate and important to you in that moment, others will likely feel the same way.

In an interview, you said that when you’re writing, you don’t start out with something to say, but rather that you’re trying to figure out an internal question and then you look to the outside world to see if there’s an argument. How do most ideas germinate? In conversations, as a result of situations, because of what’s happening in the world, or some other reason?

A mix of all three, I guess. I’m an inveterate daydreamer and usually I’ll be doing something else – washing the dishes, going for a walk, whatever – and I’ll notice that my mind is drifting repeatedly towards some subject – maybe a conversation, maybe a question, maybe a person I don’t know well but I’m curious about. I think the key is noticing when that happens but not interrupting it or forcing it…trusting your brain to do that work, and that there’s something interesting there, even if it’s not immediately clear where the train of thought might go.

One of the things I like the most about your personal story is that writing an essay that went viral increased your exposure and led to a seven-figure book deal. Knowing what you know now, should essayists and short story writers graduating MFA programs focus on literary contests or aspire to write in well-known literary magazines like The New Yorker?

Ha, well, you should aspire to whatever your heart tells you to aspire to, whether it’s The New Yorker or winning a particular contest or The New York Times best seller list. I think there’s a lot of well-meaning advice out there about what’s possible for writers, and a lot of it is very disheartening and comes in the forms of false certainty: that it’s ‘impossible’ to, say, publish a debut story in The New Yorker, or get an agent without having graduated from an MFA program, or to make a living off your writing. Well, all of those things are possible, in the sense that they have happened, and will happen again. What they are is unlikely – but it’s also unlikely, numbers-wise, that you’re going to win any particular contest you pay $20 to submit to. At least submitting to The New Yorker is free. So you might as well aim for what you actually want.

What matters, I think, is being clear-eyed about the odds, and not making sacrifices you’ll resent if a long-shot gamble doesn’t pay off.

If you hate writing short stories and never read them, but your goal is to get published in The New Yorker, and if that happens, it’ll all be worth it, and if it doesn’t, you’ll feel like you wasted your time…you’re setting yourself up for disappointment. On the other hand, if you love reading and writing short stories, and The New Yorker is your favorite magazine…of course you should aspire to be published there! And, frankly, you’ll feel that way regardless of what anyone tells you. I think the point is that there’s no guaranteed path to success in this business, so there’s no point in trying to take the ‘safe’ route. Aim for what you want, whatever that may be.

In another interview, you talked about a heart-to-heart talk you had with your father about having to settle on a stable life to afford to write after earning your MFA in 2017. Any suggestions for The New School’s class of 2020, who are feeling particularly disconnected in the middle of a pandemic pontificating about what their future looks like?

Oy. I have no advice, only commiseration. But I guess the point of that story is that, in my conversation with my Dad, I was so sure I’d hit a dead end, that my financial future was a disaster, that there was no hope, etc. And I was wrong! I was wrong about everything.

The answer to almost every question about the future, whether there’s a pandemic or not, is “who the fuck knows!”

Maybe one way to think about it is, getting an MFA is always a gamble, and it’s a choice to invest in something you love and take pleasure in and find intrinsically rewarding, even though the way it will shape your future is almost always unclear. That was as true before the pandemic as it is now. An MFA isn’t something, like, say, law school, where you might have suffered through it at the time in the assumption that there would be a stable job for you on the other side – only to see those jobs evaporate. You have already reaped the benefits of the program, and the future would have been unclear regardless.

You’ve already proven that you’re comfortable with uncertainty, that you’re willing to take risks, that (probably) you can survive on very little money, and that you’re capable of finding deep joy and satisfaction in an activity you can do alone in your house. Those are great skills to have in a pandemic! You are going to get through this, I swear.

I know you had some success with short stories published mostly online before publishing in The New Yorker. What steps did you take to get there, and knowing what you know now, is there anything you’d do differently?

Well, I took the steps everyone takes: I wrote stories, I submitted them, I took a couple of workshops and then eventually applied for an MFA. From the outside, the story is as boring as it can be, and while not all the steps along the way were pleasant, I think they were probably necessary… so no.

I’m not sure I would’ve done anything differently, other than maybe be a little kinder to myself. But that, too, was something I had to learn how to do, so it wasn’t really skippable.

You said, “I was frustrated with myself in those early years in grad school. I had the most punishing imposter syndrome. I felt everyone else knew what they were doing. I couldn’t ask a question to learn anything for a long time.” I loved that you gave voice to something every graduate student experiences. What advice would you give to newly admitted MFA students?

Again, that’s the thing about advice – it doesn’t work! I could tell you not to have imposter syndrome, that it’s incredibly common, that most everyone feels that way at one point or another…but if it were that simple, imposter syndrome wouldn’t be the problem it is. But I guess, to the extent it helps,

I’ll reiterate: you’re there to learn, not to impress people.

The less you know, the more you’re going to get out of any given class, so if you can let go of your pride and just admit when you’re confused and don’t understand something, you’ll be sacrificing the immediate reward of looking like ‘the smart one’ in exchange for the longer-lasting satisfaction of actually getting smarter. Easier said than done, obviously, but it’s the truth.

I loved that so many people thought of “Cat Person” as an essay. Have you written any nonfiction essays? Any interest?

I have! I’ve written a fair number of autobiographical essays for The New Yorker (online) and other venues, and I have also done some book reviewing, which I enjoy immensely.

There are so many debates over whether it’s worth it to get an MFA. How has your MFA shaped your writing, and was it worth your investment?

I buy into the idea that an MFA doesn’t necessarily give you anything you couldn’t achieve on your own by reading, writing, and getting feedback on your work, but it can speed up that process.

I don’t know how my writing would be different if I hadn’t done the MFA, because I can’t access the counterfactual, but I got to spend three years focusing entirely on my writing, and I do not regret that.

I went at the time in my life, and in the specific set of financial circumstances, that were right for me. Everyone has to assess for themselves if an MFA is right for them – there’s no one answer for everyone.

If you had a magic wand and could be anywhere doing whatever you like three years from now, where would that be?

God, I just want to be out of this goddamned apartment. I want to go to a massive stadium concert and then a baseball game and then to a crowded beach and then to, I don’t know, a rave. Sure, there should probably be some writing thrown in there at some point, but mostly I just want to be around people again!

*