Cousins

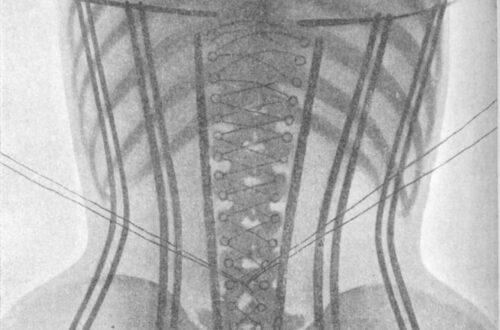

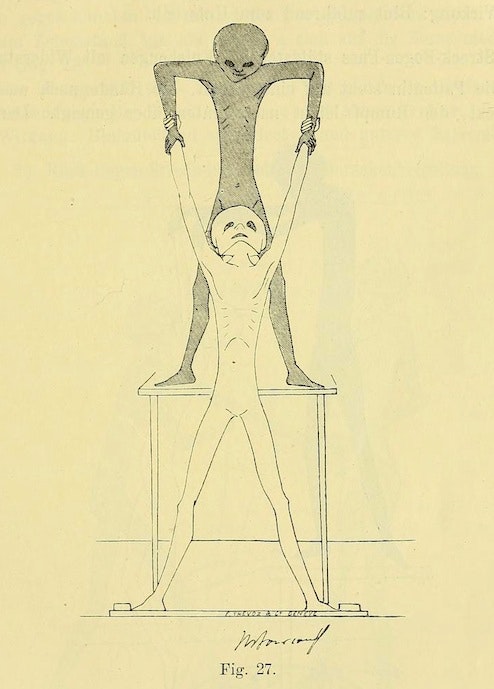

diagram by Thure Brandt (1895), Public Domain Review

by Claire Donato

A woman and her ex-partner were together for ten years but never married, despite their shared affinity for The New York Times Vows column, which appears on Sundays in the newspaper’s Style section. Every weekend, they would read Vows aloud to one another— idyllic short stories of couples meeting, falling in love, getting engaged, and marrying, presented sans red flags or conflict. Any real interpersonal turbulence was smoothed over to the pitch of a PG-rated romantic comedy movie. They cut out their favorites and neatly stacked them on a shelf in their shared office, and fantasized that they, too, would one day get married and submit their wedding announcement for consideration as a New York Times Vow.

One Sunday evening, after the woman had gone grocery shopping at the food coop, she walked in on her ex-partner taking a shower with a younger woman she had never seen. The younger woman was running one hand through her ex-partner’s thick, black, curly hair while simultaneously jerking his penis off with her other hand. Their clothes—a black fabric pile of assorted textures and shapes—were heaped on the bathroom floor like a mass grave. As the woman gazed at her ex-partner’s naked body co-mingling with that of the younger

woman, a naked sculpture of an otherworldly baby with huge celestine-colored eyes and a massive erection was displayed on a plinth in the living room behind her. Later, as they were breaking up, the woman’s ex-partner would explain that he had met the younger woman, Adrian, on a hook-up website. With an anxious but ultimately sociopathic smile on his face, he explained to the woman that he had lied to Adrian and told her he was in an open marriage.

“But we aren’t even married,” she said.

“We might as well be. Our partnership feels too close, too much like family. From this point on,” he said, “It will be better for us to be friends.”

/

A man I met on a hook-up website visited my apartment to eat grouper. He wore a black sweater and black pants and had a head and a face, unlike his profile picture, which only captured his half-naked body from the neck down. He had a crooked smile, a Roman nose, and the phrase LOVE AFTER PAIN tattooed on his left hand. His hair was also black, and curly and thick. I wondered if his pubic hair was too, though our intention was to develop an

emotional connection before crossing any sexual boundaries. I set this parameter in order to remain in control, but I could not help but fantasize about losing it—a pattern I tend to repeat when I seek out short-term relationships.

As we sat at my kitchen table and ate, the man talked about his outsider art collection, his penchant for sacred harp music, his cottage upstate, and his woodworking practice. How did he have money for a cottage upstate? Although he was not wearing a wedding ring on his left finger, he eventually began to talk about his wife, whom he ecstatically called “my wife.” “I’m a very bad husband,” he said. “I cheat on my wife all the time.” At least he wasn’t lying about being in an open marriage!

There was a way the man expressed his self-loathing while cutting the grouper that was unusually beguiling. He sliced the fish as if he were harming it by running his knife through its center—which would be the case if the grouper were still alive, as neurobiologists confirm that fish have nervous systems and respond to pain. Earlier that day, I read about the practice of catch-and-release fishing on PETA’s website, wherein a fish is caught by a fisherman before it is let go. So states the website: “Catch-and-release fishing is cruelty disguised as sport.” But the National Park Service’s website claims otherwise. “In catch and

release fishing anglers immediately release native fish—unharmed—back to the water where they are caught,” it says. “When done correctly, catch and release methods result in high survival rates.”

Upon observing his cutting style, I told the man all of this, then looked down at my own half-eaten dead fish seasoned with lemon, chili pepper, ginger. It was covered in translucent juices and smelled briny and sweet, like the ocean or freshly cut grass.

Before the man, who looked uncomfortable that I had just said a lot about the ethics of killing fish, could respond to my inquisition, I asked: “Does your wife have a name?”

/

My first pet was a betta fish named Rudy. I don’t remember where I adopted him. He was the color of menstrual blood, with a spectacular fin display that resembled flower petals. I liked to sit and watch him swim laps across the fish tank, from one glass wall to the next, and then back and forth again, as if he were competing in the 1992 Summer Olympics. I was six years old then, and although Rudy was ageless and couldn’t express pain, we became two lonely

creatures inhabiting a room devoid of anything but moving images of swimmers competing in their lanes. They aired live on the television next to us.

Today, there exists an activist group who protests the trade and sale of betta fish. I know this because I frequently walk through the Union Square Greenmarket after psychoanalysis. One afternoon, I heard a protest—the sound of voices through bullhorns— emanating from Petco, a store located near the upper northwest region of the Greenmarket. Upon closer inspection, I observed a group of demonstrators holding cardboard signs containing enlarged photographs of betta fish, brightly colored and highly territorial fighting fish who exhibit aggression toward one another if housed in the same tank. In my memory, the text printed on the activists’ signs declared something like “STOP PETCO.” But words are only rendered animate by the subjects carrying them. When they cease to exist in print and are consequently disposed of (on cardboard posters or 8 ½ by 11-inch sheets; on paper napkins or used receipts), their meanings drift away, and only energetic traces of the alphabet remain. Yet words want to be alive, they crave oxygen, and they possess an uncontrollable desire to feed. Analogously, before he transformed into light, Rudy existed in a tank where, as a form of

protest, he consumed all his companion fish. He dominated them, ate them up, then left them to die at the water’s surface. What more can be written? He wanted the tank to himself.

/

One week later, I walked three blocks and descended a concrete staircase toward a subway platform where I awaited a train that would take me to see a movie. My phone had recently fallen into the shower and suffered water damage, much to my chagrin. While I awaited the arrival of a replacement phone, I could not readily browse the hook-up website where I had recently met a lovely, married environmental lawyer with thick, black, curly hair. He reminded me of my ex-partner with whom I no longer speak. Even though I had entered into our arrangement with a casual encounter in mind, I always became a spigot of grief following his departures. For days, I would cry and cry and cry, awaiting his return. Now drained from crying and sans the presence of my phone, I possessed electric energy. I was porous, like a human quartz or sponge.

And so it happened, as I descended the concrete staircase and walked toward the subway platform, that I made eye contact with an alien with neon hair the color of a tropical

fish whose face was strangely contorted. One side of it did not seem to move, while the other side was animated. His features created a lack of symmetry despite the fact that his eyes, bright blue as celestite, were aligned. His arms were covered in tattoo sleeves, and one of his forearms was concealed in black ink, a redaction or form of self-censorship.

Noticing our eye contact, the alien walked toward me. When we stood face-to-face, he paused.

“Did you ever work at a pet store?” he said.

“No,” I said, holding open the book I was reading about Zen Buddhism and the cessation of craving.

“That’s funny,” he said. “You look like the love interest from Rocky.”

My heart pounded.

“You’re even skittish like her,” he said.

I nervously laughed. “I have not seen the movie,” I said, and a train passed underground. It was very loud, and I was thankful for its sound, hoping that I would not have to continue talking to this alien.

“You have not seen Rocky,” the alien repeated back at me. “The character that looks like you is very pretty and takes care of turtles at the pet store.”

To which I did not respond.

And then the alien asked me: “Do you like marijuana?”

A second train passed, breathing a sound of relief. I motioned my hand in a gesture meant to communicate the French phrase comme ci, comme ça, although it had been some time since I had consumed marijuana, and I did not want to be communicating with this man who had permeated my boundary, which was perhaps not a boundary but an invisible wall between myself and others, destabilizing my sense of self and leaving me receptive to the world and its aliens—which is what this man was: a very high alien. And the fact of this alien’s predation was not a fact but a feeling in me. It is not what happens in the mind that counts, but rather how one relates to the happening. And in this happening, I was not relating. I was withdrawing into my shell, O skittish turtle whom I tend at the pet store.

“Give me a second,” the alien said, and he subsequently walked to a black trash can and spit in it. As he spit, I turned my head, first to the left, then to the right. There was a boy beside me whom I am calling a boy because he looked younger than I, although this boy was

of course a young man. He was wearing a black sweater and black pants and had a head and a face. His hair was also black, and curly and thick, and I wondered if his pubic hair was too. “Help me,” I mouthed.

The young man took out his headphones, was now also porous.

“Can you help me?” I mouthed.

The young man nodded and took my arm. “You’re my cousin,” he said, and walked me toward the front of the subway platform. The fact that he called me his cousin made me feel a transcendent sense of inner calm and security: cousins protect each other. Nevertheless, the alien was walking behind us, following us toward the front of the train car. As we walked together, my new cousin told me his name, which I cannot recall. Was it Cameron, an anagram for romance, or Edward, derived from the Old English meaning prosperous guardian? “Where are you going tonight, Cameron or Edward?” I said.

“I’m going to a concert,” he said.

The alien began to yell incoherently, his voice echoing through the subway station. “I’m taking myself to a movie,” I said.

“Oh,” he said. “Which movie?”

Claire Donato is the author of three books, most recently Kind Mirrors, Ugly Ghosts (Archway Editions, 2023). Recent writing has appeared in Parapraxis, Forever, The Brooklyn Rail, Fence, The End, The Chicago Review, and GoldFlakePaint. She also contributed an introduction to The One on Earth: Selected Works of Mark Baumer (Fence Books). In addition to writing books, Claire makes music, illustrates, and has a 35mm photography practice. Currently, she works as Acting Chairperson of Writing at Pratt Institute, where she received the 2020-2021 Distinguished Teacher Award. She lives in Brooklyn with her cat Woebegone.