Cabinet of Curiosities

by Meredith Jelbart

This cabinet, which I gift to you, my child, has ten rows of ten small drawers. Standing flat against the wall, it takes up little space. It is beautifully crafted; dark wood of the drawer front meets the lighter interior wood in dove-tailed joinery, a dark tail interlocked with a lighter one, a darker, then a lighter and so on.

It has come down in our family, from a great-uncle’s garage, to my study. To wherever you may choose to keep it.

You could say it’s an heirloom. Airloom? On which might be woven those fine webs hung across your childhood window to catch bad dreams? Did a clutter of dark matter fall out there beneath the sill, like rubbish blown against a sea wall? To disintegrate in the light?

One hundred drawers. In some of which I have placed items of interest. I will not be able to find offerings for them all. The rest I leave free for you.

*

Here, for example, is a drawer filled with seashells, a random assortment, easily found on most beaches, if you look. Some cowries. These were used as money across Asia and the Islands. No more beautiful than other shells, they are hard and durable and would survive being traded from one market place to another. Also, once fixed into masks, they do become the most riveting eyes.

*

Another drawer contains only small black and white seashells. Zebra snails. Striped moonshells. Magpie-banded shells. Tiger cowries. So elegant, to have eschewed all the gaudier colours in favour of this minimal palette. Some have simple black and white stripes, but others seem made of infinitely fine ribbons sliced from a checkerboard and coiled round upon themselves. The tiny pixels. Challenging focus.

Shake the drawer and feel your eyes flicker.

*

The ‘fl-’ words.

A few of these drawers contain only words, written each upon their own small cards. Through which you may flick and flitter. As they flutter. Like other things here, words are easily found, may give pleasure, and are therefore worthy of attention.

Is there something in the action of lips and tongue, producing that ‘fl’ sound which immediately suggests insubstantiality with a touch of the absurd ? ‘Flummox.’ ‘Flibbertigibbet.’ ‘Flotsam.’ Those mornings when you may feel a little flotsam? ‘Flabbergasted,’ everyone’s favourite.

*

This drawer contains butterfly wings. It is an urban linguistic myth that ‘butterfly’ is a corruption of ‘flutterby.’ I am saddened by this, the connections seem so perfect. Beyond the creature’s death, wings seem to go their separate ways, drifting up singly into corners among dust and cobwebs and loose leaves. I am particularly fond of the cabbage moths. Simple but gleaming white, they drift about the garden like random points of light. Damaging cabbages, I suppose. Butterfly wings are covered by tiny, light reflecting, overlapping scales. Lepidoptera – lepi, ‘scale’, pteron, ‘wing’. Touch a wing, however gently, and note the infinitely fine sparkling dust, the scales, which will come away on your fingertip.

*

A drawer containing feathers. The central shaft has paired branches, or barbs, which possess further branches, barbules, which in turn possess infinitely tiny barbs, which hold one barbule to another. Detached from the bird, the feather may separate into sections, but by smoothing it very carefully between your fingers, you may make it whole again, feeling the tiny hooks meshing together. The more brightly coloured feathers are from parrots. I could suggest the species, but you may care to look for yourself.

*

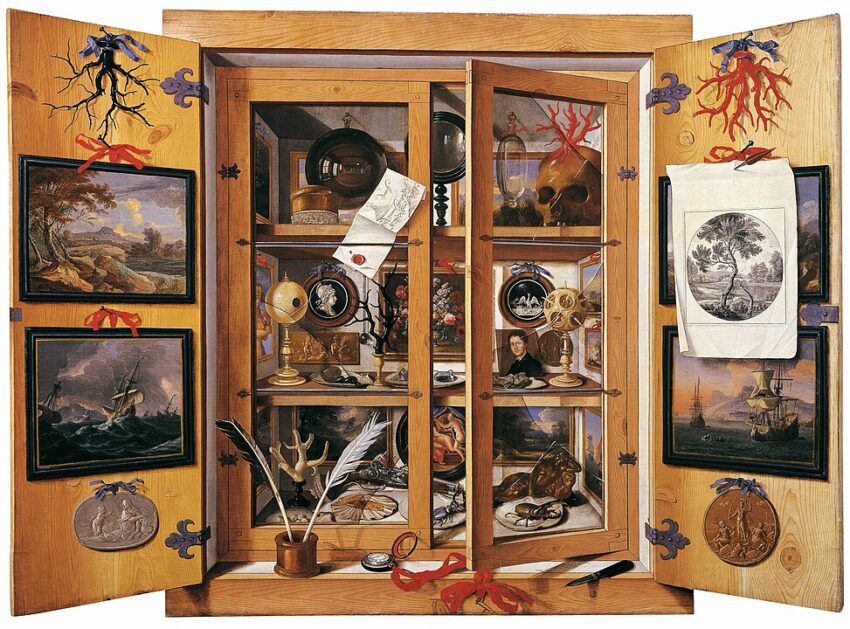

The earliest illustration of a Cabinet of Curiosities is an etching, dated 1599, by Ferrante Imperato, an apothecary of Naples. It shows a room of modest size, absolutely and entirely covered in items of interest. There are shelves, cupboards, jars, bags, books, all up the walls. Stuffed birds perch upon the architrave with other assorted fauna. The arching roof is covered in marine creatures, arranged in pleasing orderly patterns. And who would have thought to keep the crocodile on the ceiling?

Just how does anyone access this room? I would like to think that the approach is a plain and undecorated hallway; the door is ordinary, wooden, of no great size; then that door is thrown wide open to reveal . . . .

A Cabinet of Curiosities, a Wunderkammer.

May you have curiosity.

May you be attentive to wonders.

*

Small off-cuts of Venetian glass.

The displays in Venice’s glass shops are both wondrous and appalling.

Glass jelly-fish floating in deep blue glass; characters from Disney; the elaborate multi-coloured, multi branched chandeliers ten to fifteen feet across; the American eagle slightly larger than life-size.

But millefiori glass. One thousand flowers. Long extruded pieces of glass, holding the pattern within like rock candy, are cut down into small pieces, which may be arranged tightly beside one another, as if in a bouquet, then preserved within clear glass. Look into paperweights of millefiori glass and feel yourself becoming lost into some other world. It is also like looking down upon a coral reef.

What is left, when the millefiori core has been cut down, is a small nub with the flower shape opening out within it. In all of Venice these were the only things I wished to own. Here is my selection.

*

This drawer contains slivers of glass, found on the beach, worn down by the sea and sand – dust to dust, silica to silica – like cough lozenges worn down by the tongue, so the colours are muted and the edges are soft and pleasing to the touch.

*

Red autumn leaves. Placed between wax paper and pressed within a large book moisture is removed, but the colour of the leaves remains. I used my Shorter Oxford Dictionary, which the internet has rendered useless, a curiosity from bygone days. Pressed flowers were popular in Victorian times. But reducing the complexity of blooms to one dimension is so unsatisfactory, the colours correct but the shape . . . Like floral road kill. But these leaves are almost perfect. Light may cause them to fade somewhat. Perhaps it is better to keep this drawer closed.

*

There is nothing in this drawer. But just take it out and breathe in. Yes, it is cloves. I had to remove them after a little time, or the scent would have permeated the entire cabinet. Which, formally, is called an apothecary’s cabinet. Apothecary. Does uttering this word require a clearing of the throat, which might be the kind of problem that brought you to consult such a person? Who might have used these multiple drawers to contain all the individual ingredients for medicinal potions. Cloves for toothache. Also, liquorice, sage, willow, fennel, mint, garlic, chamomile. Plus gold, dried earthworms, candied rose petals, human urine and earwax. What people will believe!

*

‘Gormless’. I do not wish gormlessness upon you but it is such a pleasing word that I have placed it here, on its card, on top of others which imply elusive opposites, lost somewhere in the lexicographic ether. From which they might be rescued? ‘Gruntled.’ ‘Couth.’ ‘Kempt.’ ‘Effable.’

*

A tool with a bone handle, fine metal wire ending in a metal equilateral triangle, and the curving scissor or tong thing with blunt gripping ends. I do not know their purpose, but they were in this drawer, so I leave them to you to muse upon.

*

In this drawer I have placed two crochet needles – one of a normal size, large enough for wool, one exceedingly tiny.

The tiny hook is for filet crochet. Using only fine white cotton thread, images can be created: the emu and kangaroo for Australian Federation; the soldier with his rifle, 1915, ANZAC, ‘Our Hero, we’re proud of him’; the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge with the date, the bridge, the ferries, yachts, bi-panes and the seagulls. It is all done with pixels. A stitch is filled in with white cotton, or it is not. The system is binary, as in a computer.

Alan Turing found knitting an effective way to remain calm. At Bletchley he knitted gloves – useful in English winter – but also Moebius strips, which could become scarves.

Hyperbolic geometry and fractals. ‘A fractal is a self-similar subset of Euclidean space whose fractal dimension strictly exceeds its topological dimension.’ Good luck with that. But perhaps you are mathematically inclined. Since Euclid, mathematicians have speculated about hyperbolic geometry, which paved the way for Einstein’s theory of Relativity. But they could see no way to create a model of such space – beyond the capacity even of twentieth century computers – until a professor of mathematics, who was also a keen craftswoman, produced a model in crochet, which is naturally a fractal process.

Fractals are everywhere in nature – cauliflowers, pineapples, frost patterns, defrosting patterns on Mars, ferns, fungus. Coral reefs.

The Crochet Coral Reef Project involved 10, 000 craftspeople producing thousands of cubic metres of woollen reef. After the coral bleachings of the last decades the artists have produced white reefs, sometimes made from plastic. They are haunting. But everyone would return to those in colour. In life, you may not be able to turn to coral reefs in colour. I am so sorry about that.

I would not recommend filet crochet as an activity. That way – in its tiny obsessive detail – madness may lie. But fractal ruffle scarves? There you might be, crocheting your way into higher mathematics, without giving it a second thought.

*

A drawer of skeleton leaves. Weathered down to just their veins. A fractal system.

*

A drawer of seashells, broken lengthwise. See how the spiral develops with such grace, the volume of each chamber equal to the sum of the two which precede it. This is a Fibonacci sequence, related to, but not quite identical with, fractal geometry.

*

This drawer contains a treasure map, tracing the local creek, X marks the spot. I suggest that dawn and dusk are the best times to head out on your quest.

When specimens of the platypus first reached England, scientists were sceptical. Mummified mermaids in museums all up and down the country, grotesque creations, a fishtail sewed onto the upper half of a baby monkey, whose teeth are often bared as if in horror at the unnatural fusion forced upon it. So, a creature with a duck’s bill, a cat’s body, webbed feet, a beaver’s tail, venom carrying spurs, and it lays eggs? Yeah, right, the scientists thought, snipping about in fur, seeking tiny tell-tale stitches.

I have seen a platypus in the wild just once. An unassuming creature looping about in dark water, making no song and dance about its exotic attributes. Will they still there for you to see? Unlike the mermaid, never seen on this earth, or the dodo, seen no more. Let’s not abandon hope.

*

In my experience, abandon is never gay. May you never be abandoned.

*

Blue plastic straws and bottle tops, blue ribbons, blue tinfoil chocolate wrappers.

What is it about blue? It is the colour that writers so often meditate upon – the blue of distance, of longing, the blues. Which perhaps makes sense since we all live daily with the sky, and, if we are lucky, with the sea. A friend, who came close to dying, experienced no bright white light, but an all-enveloping blue. My blue, she may say, dreamily, being among that subset of people who neared death and were reluctant to come back.

Bowerbirds seek only blue. This selection is a replica of the items in my garden, which the bird had scattered all around his bower. I leave the originals out there, because I hope he will return.

*

A collection of words appropriated from other languages, since we have no precise English equivalent and they seem so necessary. Schadenfreude. How could we get by without that? Saudade has become popular of late – a yearning for some thing or place or happiness which may never have existed. Relatedly, fernweh – a longing for far off places where you have never been. Longing contains the meaning ‘to literally grow long’ as might happen stretching towards the object of desire.

*

Bones. So extravagantly fine, yet they supported some living creature all of its days. From the beach again, many of these will be from birds, hollow, to produce minimal weight in flight. A migratory bird, perhaps. Red necked stints, less than 50 grams each, breed in Siberia then fly over 10,000 km to southern Australia. Amazing that this ever seemed a good evolutionary plan.

*

This cabinet I bequeath to you. Be, ‘around’, cwethan, ‘to say’. Given in words, a promise, a blessing.

The Be list.

Behold. Be – ‘thoroughly’ – hold. Though versions of this word occur in other languages, it is only in English that the meaning is to look upon, rather than to grasp or retain. May you find wonders to behold. May you not be beholden.

Bemused. To be intensely surrounded by a person or force of inspiration. This sounds no bad thing.

Benighted. To be surrounded in night. May you only be benighted in the night.

Bewildered. To be thoroughly led into the wilds. Rewilding movements have reclaimed areas of Europe, England, the Americas, and there are spontaneous rewildings in the wake of war and disaster. Wild animals, many of them rare and endangered, have settled peacefully into the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea, and in Chernobyl swallows and songbirds nest in the cracked sarcophagus shielding the remains of Reactor 4. May you have access to the wild.

Neither beguiling nor beguiled be. Let there be little guile in your life. Witches likewise.

Betrothed. Whether or not you are literally betrothed, it is good to have truth around.

May you not be bedraggled, bejewelled, besmirched, belittled, betongued, beleaguered or bedevilled.

May you be beloved.

Meredith Jelbart is the author of a short stories collection, Max, and other stories, and the novel, Free Fall. Her writing has been published in the Australian magazines Lip, Island, Meanjin, The Griffith Review; on Adda, the Commonwealth Writers’ website; and in The Perch, from Yael Medical School. She is currently working on a novel and a memoir/social history work about her family. She lives on the south coast of Victoria, Australia.