Day at the Zoo

by Daniel Webre

On another day at the zoo, not this one, I had the place almost to myself. I even had my own private animal show. On this day, however, things were different. I was hurrying along until I got to the foxes. There was a red fox with a white coat who intrigued me. She was there as before, but on this day I left the fox enclosure to investigate an unfamiliar noise. The caged-in area next door looked similar to the one I’d just left. It took a moment of scanning the interior before I could locate the source of the noise. There were two noises actually. These were the sounds of a tortoise making love. I say “tortoise,” singular, because only one of the tortoises involved was actually vocalizing (which was a revelation in itself because I didn’t think a tortoise could vocalize). This was the first of the sounds. It was a grunt and a squeak combined. The other tortoise—the lady tortoise—was calmly munching lettuce. She had climbed all the way into her food tray, a round, shallow affair of the sort people around here use to serve boiled crawfish. The male timed his grunts to his thrusts. Or maybe it just sounded that way. The other noise was the clack of his shell against hers, or else his shell knocking, against the hard outer edge of the red plastic tray. The other three tortoises in the enclosure kept their distance, though none of them expressed much concern. I nervously considered the children romping around on the playground just across the sidewalk from this exhibit, and decided to move on.

#

What I’d first mistaken for a train depot turned out to be something called a butterfly room. I didn’t recall seeing it on my last visit, and I wondered how long it had been there. A paper sign said “Open,” so I tried the door and went in.

“The ones to your right are blue morphos.”

Startled, I looked for the voice rather than turning to the right. My view was blocked by a glass display case, and I wondered how the person speaking knew I was there. I had to find my way around the case before I could get a direct view of the speaker. She was aged but somehow youthful, her eyes the same shade but a more muted blue than the morphos. I wondered why the room smelled like popcorn.

The woman’s long gray hair made me think of sea spray. She swept her hand in a gesture that took in the entirety of the room. An extensive collection of framed specimens covered the walls at eye level. “These all belonged to that man over there. These were his butterflies. But he couldn’t take them with him.” I nodded as though I had grasped her meaning.

There was a pencil-drawn portrait of a man on one of the walls. It was surrounded by butterflies. The contrast between the dull graphite and the vibrant insects was striking. The woman continued talking. She said the man had lived in New York, but she couldn’t tell me how the man and the zoo had come together. The text displayed next to his portrait said he’d died some fifty years before the zoo had even opened. I asked her about some large green specimens. But a different woman was speaking now. “Where do we buy the tickets for the railroad?” I hadn’t noticed her come in. She had two small children with her.

“By the popcorn machine,” the guide answered.

“There’s no one out there. The train’s about to leave.”

The guide kept smiling. “That’s where they sell them.”

A train whistle blasted and the mother left in a huff.

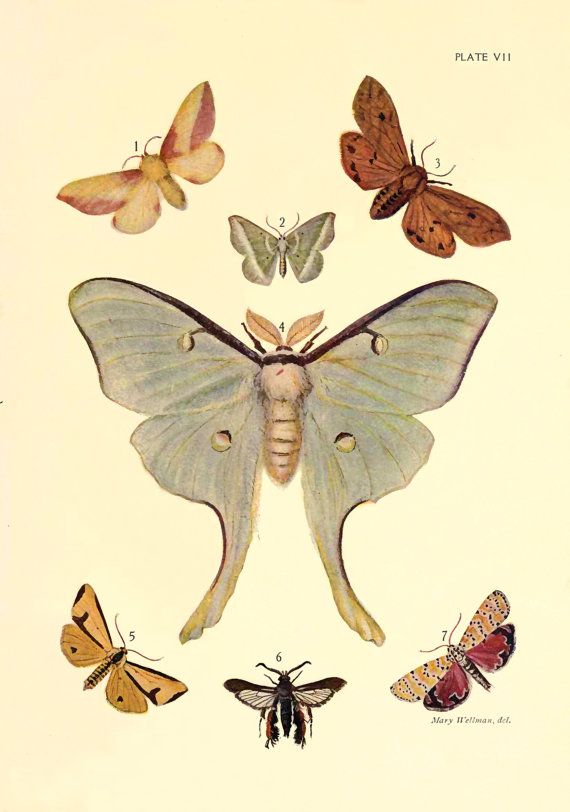

The guide turned back to me. “I don’t know about those green ones.” Then she pointed at the wall directly to her right. “Those are moths over there.”

I didn’t see any moths, until I realized she was pointing through the wall.

She continued: “Google says there’s supposed to be colored ones. But there aren’t.”

A wall covered in owl eyes stared back at me. I complimented her on a Luna moth.

“What’s that?” she said.

“The pale one. It’s got a greenish-yellow blush. Like the moonlight, I suppose.”

She couldn’t have seen it from where she was sitting, but she nodded. She seemed eager to discuss butterflies again. “Those by the door are called swallowtails because of the shape of their wings. Some have wings in the shape of a V. Others have wings that go straight across. I think those look like bowties. Don’t you think those look like bowties?”

I nodded and pointed to a set of paper butterfly cut-outs among the merchandise for sale behind the counter. My sister had a few of those at her house. When my nieces and nephews visited one day, they presented each family photo on the wall with a butterfly bowtie. “I know exactly what you mean,” I said.

Aside from butterflies and moths, one case held a set of iridescent beetles, another only contained cicadas. The cicadas were arranged by size in their case so the one on bottom had nearly a five-inch wingspan.

She caught me looking and said, “I saw a program once where they came out with a whole stick of those. They were putting them on the grill like . . . Oh, you know . . . What do you call those things?”

“Shish kebobs?”

“Yes. Shish kebobs . . . No thank you.”

I agreed with her. I didn’t want anything to do with that either.

“I don’t think I’d like the texture,” she said. “Could you imagine the texture? It would be even worse than those little rubber bands you fry and eat . . .”

“Calamari?”

“Calamari. I don’t care for scallops either.”

I wasn’t quite sure why, at this point, I was still in this butterfly room, having this particular conversation with this person. No one else had come in since the mother looking for tickets, and I wondered how many other people ever even noticed it was here. I had been hoping for live butterflies.

“I went to Mexico once,” she was saying. “They had these metal bowls there that looked like silver, only that isn’t what they were. The insides looked so silvery that they were blue. It was only later I realized they were the wings of the blue morphos.”

“You mean they were colored somehow with the pigment from the wings?”

“What do you mean?” she asked.

“With the powder?”

“There’s powder?”

I’ll admit, I was taken aback by this. “Well, yes,” I continued. “At least, I think so. I remembered catching butterflies when I was a kid and touching the wings of one. The color had come off in my hands.”

“Is that right?”

Now she had me doubting myself. A butterfly lady should know what was true or not.

“And the wings are clear under that?”

“That’s how I remember it, yes.” Of course, after that time, I left them alone. I was just a boy. I hadn’t meant to cause any harm.

“Hmm. You know, I tried lobster once and didn’t like that either. That was at Albertson’s. I’ll bet they could make it taste good on a Teppen table. That’s at the Japanese restaurants. They can make anything taste good on one of those.”

It was time for me to be leaving, but I wanted to make a graceful exit.

“Look at this,” she said. She was holding up a cell phone with a picture on the screen. “Boo at the Zoo. There’s a ghoul driving the train.”

He looked like the crypt keeper from Tales of the Crypt.

She advanced the frame. “And look. There’s cobwebs everywhere.” She pressed the button again. “Here’s my favorite. There’s a skeleton bride in the very back. Can you see her dress?”

As odd as our conversation had become, in a way, I felt grateful for it. I was no longer a strange older man touring the zoo by himself. I was a real friend of the zoo—just like my card said—an esteemed and honored guest of someone who belonged there, someone arguably much more unusual than I felt myself to be. The woman was kind, but she made me uneasy, and I knew I couldn’t stay in this butterfly room forever. Nor would I want to.

“I had hoped there’d be live butterflies,” I said, immediately regretting my lack of sensitivity.

“A flight room would be nice,” she said. “They’ve got one in Galveston at Moody Gardens. Maybe we could put a small one out here.” She gestured toward a dormant flowerbed just outside the window to her left. “There’s just not much space.”

“But what you have is nice,” I said, trying to make amends. “You don’t usually get to see this many different kinds of butterflies all in one place.”

“No, you don’t. The best collection around here, though, is Moody Gardens in Galveston. There’s a butterfly festival coming up on the Rio Grande in Texas. But I went once, and there wasn’t any water in the river.”

It was getting difficult to leave.

“The Festival of Lights is approaching. The zoo will be open after dark. You should come back.”

“I will,” I said. “Thank you.” I was already walking toward the door.

“Come back,” she said, smiling.

“I will,” I said, and then left.

Daniel Webre's work has appeared recently in The Coachella Review, MUSE Literary Journal, Stoneboat Literary Journal, Permafrost Online, The Rush, and other places. He lives in Louisiana.