Motel for Sale

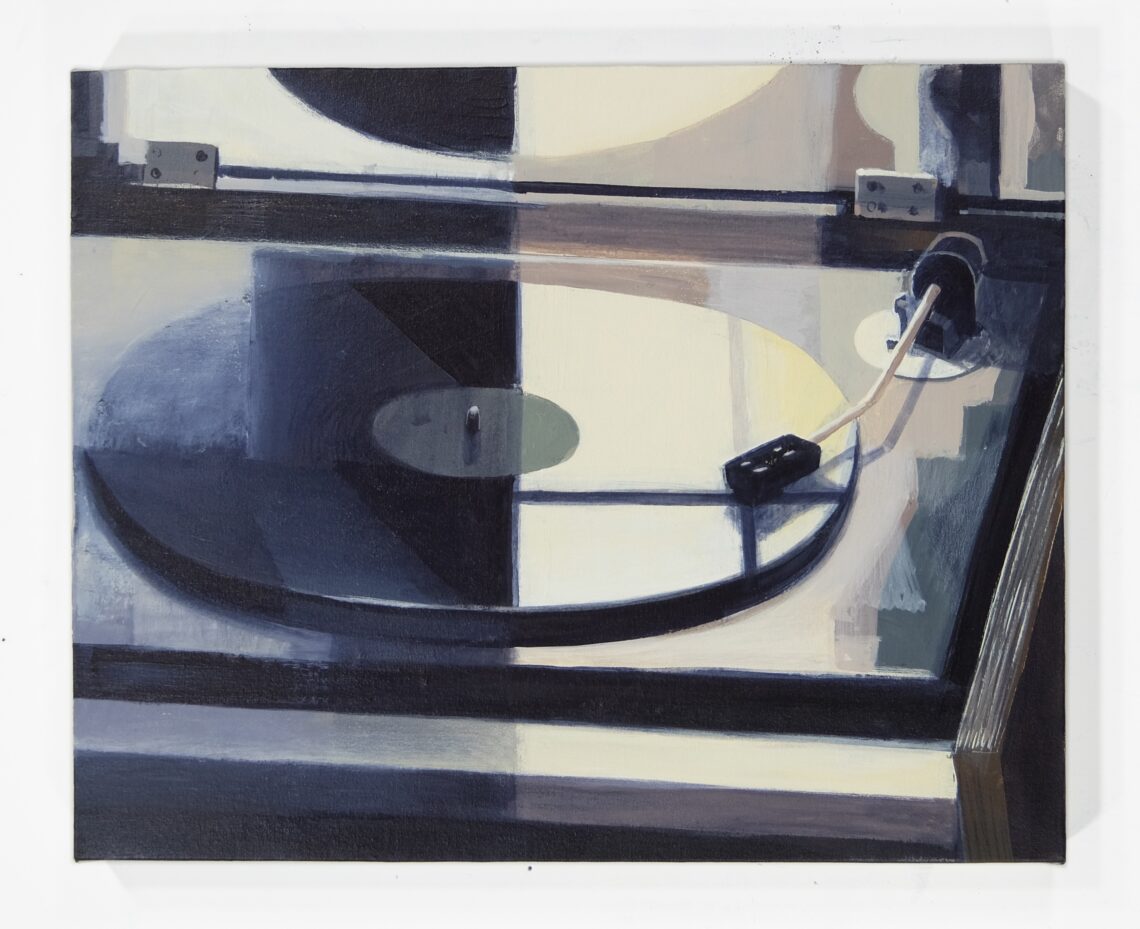

Art by Matt Bollinger

by Katie McDonough

The day before the motel sells I’m on a train headed upstate, trying—and failing—to focus on work. This is an ill-timed trip: It’s mid-week during the busy season at my job, and I have a young son at home. But as dutiful as I am, I am equally sentimental, and I don’t want to miss my chance to see the place one more time.

When I arrive at the train station my mom is waiting in the parking lot. “Is it really going to happen?” she whispers goofily, punch-drunk. She and my dad have spent the past week emptying out the motel for the buyers, who, judging by their aloofness over eighteen months of negotiations, have not yet decided if they’re going to go through with it.

Mom hasn’t eaten anything but crackers all day, so we pull into the butcher shop so she can get a sandwich. I wait in the car, laptop open, and send a few emails using my phone as a hot spot. I feel the way I always feel when I come back here: fragmented and a bit self-conscious. At any moment a former neighbor or classmate could appear and force me, with catch-up small talk, to regress back to my child self. At the same time there is an effortless familiarity to everything around me—the stores where my family’s been shopping for decades, the roads I could drive with my eyes closed—all the places I intentionally left behind.

When Mom returns with her sandwich we continue north on the stretch of Route 9 that is the setting of my early life—the way to school, to friends’ houses, to the mall. We pass the bowling alley and the pizza place, the Catholic church my grandparents attended, and the Stewart’s where we’d often stop for make-your-own sundaes or a half-gallon of milk.

My laptop is still open, but my brain is straining between my two lives: past and present. The past is winning. I close my computer, and when Mom asks if I want to stop at home first I say no, let’s go straight to the motel.

My distinction between the motel and “home” is debatable. We lived there until I was six, and even after we moved to a small town a mile away, we were there every summer and other times throughout the year, engaged in the endless, grueling labor required to keep the business running and the property from falling into disrepair. In July of 1981 my parents were in their early twenties when they bought the place for dirt cheap because of the shape it was in—abandoned, decaying, vandalized. They fixed it up and ran it on their own for several years in addition to their other jobs, and as soon as my younger brother and I could swing a hammer and strip a bed, we became their workforce.

When we pull into the horseshoe-shaped driveway Mom stays in the car to finish her sandwich while I get out and wander. She is sick of the place and doesn’t care to reminisce, so I do it alone, walking the property and taking photos, comparing what I see now to the images in my memory. There is the dingy white colonial with forest-green shutters, my first home, showing its age at nearly two hundred years old. There is the row of matching cabins, like the house’s little children, the motel rooms I spent summers cleaning with young hands. There is the lawn that I raked and mowed, and the pool, now filled in, that I skimmed for leaves and creatures dead and alive. There is the motel office, where we greeted guests, gave them their keys, and wished them a nice stay while silently wishing we could trade places with them. There is the basement where I spent hours with my father, assisting with repairs or aiming a flashlight, burning with boredom and resentment. It was less the tasks themselves than the never-ending-ness. I felt like my pet hamster in his wheel—going and going and never getting anywhere.

It was my dad who set this pace for our family, beginning when he first suggested to my mom that they buy the motel. I say “suggested,” but that’s not how he operated. Once he decided something, that was the program, and everyone else had to fall in line. The military lingo is appropriate for my dad, who spent nearly four decades as an officer in the National Guard.

The motel overrode everything. It was the reason we were always late getting places; it was the reason we rarely went on vacation. It was the reason why I felt so unlike my friends, whose lives seemed so normal in comparison—the only work ever required of them being homework and the occasional chore.

Time crawled and crawled, and then, miraculously, I was free. I left for college at seventeen, elated that the motel was no longer my problem. For my parents and brother life went on as before, but I didn’t spend much time thinking about that. I was immersed in the making of my future, which I’d vowed would bear no resemblance to what had preceded it. And I made good on that promise, moving to one city and then another, living in shared apartments and working office jobs in my chosen field. Whenever I went home for a holiday or family event, I inevitably ended up at the motel, helping with this thing or that, and walking around like I am now, remembering. Then I’d rush back to my city life, only to find myself writing about it: those cabins, that pool, and the girl who cleans rooms and dreams of escape.

My parents put up the motel for sale in 2008, but due to the recession and a slew of other variables, for fifteen years the For Sale signs went largely unacknowledged. A gas station chain and a storage company briefly expressed interest. Even Stewart’s considered it for a new location at one point, then chose a spot further north. For a long time, nothing. Then came these folks, who’ve spent months investigating what it would take to switch from well to town water, and assessing how much of the property is wetlands, until here we are, the day before closing, wondering if it’s really going to happen.

It’s early October and the motel is golden with afternoon light, lovely despite its decrepitude. I take photos of the cracked sign with changeable letters advertising “efficiencies, weekly/monthly rates” and our old phone number that I still have memorized. I take photos of the tree, reduced to a stump since a lightning strike, where we buried our dog Lucy, the motel’s unofficial mascot. I take photos of the particleboard pool shed and the two cushionless, vinyl-strap pool chairs and the mini forest that’s grown up around them. I take pictures of the cabins I lived in as a teenager, when we were between homes and the motel house was occupied by renters. I take photos of the cluster of trees at the edge of the woods where my brother and I used to play, tossing each other in the hammock left by a guest and setting traps with frayed rope and broken cinderblocks.

Nearby I find a rusty, wood-handled pickaxe and shovel that at some point fell to the ground like departed lovers and are now being reclaimed by the living, brown earth. I remember using these tools to dig up rocks so they wouldn’t snag the lawn mower blade. I remember the feel of their handles and the weight of them, the clinking sound when metal met rock. If all of that happened and those tools are now lying here disintegrating; if this place is ours and soon will not be; if the new buyers tear it down as they supposedly plan to… will we have accomplished anything here? Will our time in this place have meant anything at all?

All I know is that once I was a girl standing in this very spot, and now I stand here again, a forty-year-old woman with a seven-year-old son. I’ve taken him here a handful of times and told him stories from my motel years, but he doesn’t understand—and that’s by design. I’ve fashioned for him a childhood nothing like my own. He’s a city kid, walking to public school, taking the subway to soccer practice, and living in a rented apartment my husband and I could never afford to buy. Aside from taking out the trash two days a week, we have none of the responsibilities that come with owning a home or running a business. Sometimes I feel ashamed of this. I was once so skilled, so tough, and I’ve let myself go soft. We should have left the city and bought a home rather than renting; for years now we’ve been throwing our money away. For my job I spend my days sedentary, emailing. To be in nature takes real effort. It’s rare that I work with my hands now, that I make something I can look at and touch.

Everything at the motel has been touched by my family, from the crumbling cabins to the overgrown lawn. I’d like to stay and keep taking photos, but I have work to finish, so Mom and I head to the house. Later I suggest to my parents that we go out to dinner, and tired as they are, they agree.

At the restaurant we sit in a booth, my parents on one side and me on the other because they want to look at me. This delights then swiftly devastates me. My parents are not together anymore, and even as an adult with a family of my own, I wish they were. Their separation is still new-ish, as is the reason for it: my dad’s decision, at age 63, to come out as a transgender woman. It’s been four years since Dad revealed this secret, and I’ve grown accustomed to it and to who she is now. But today’s visit to the motel—and its impending, possible sale—has me uncomfortably nostalgic for the time when my dad was still a man and my parents were still a couple and, yes, even for the blazing summer days I spent cleaning rooms, cooling off in the pool, and eating take-out pizza with my family at the picnic table beneath the now-gone tree.

Our dinner conversation is mostly light and laced with funny, poignant memories, but we’re all aware of my brother’s absence. Since Dad’s transition he has distanced himself from the family, and recently moved several states away. We try not to talk about my brother, but it’s impossible. Those years at the motel it was all four of us. Now it seems unlikely that we will ever be all together again.

The mood darkens, and while Dad and I try to articulate our peculiar grief at saying goodbye to the motel, Mom stiffens. She can’t wait to be done with the place; she has no love for it and will not miss it; it took too much from her. “I’ll never get those years back,” she says with anger in her voice and tears in her eyes. She won’t look at Dad, because that’s who she blames for it—the motel was his idea, his baby, after all. But the man who forced it upon all of us decades ago is gone.

Now Dad sits quiet in the restaurant booth, long hair falling around her face, but I can still see her regret. Since transitioning my father has become much more expressive, sharing her desire to go back and do things differently. But she can’t go back, and neither can my mom. For me the motel is the setting of memories and stories, a place I fled long ago, but my parents haven’t had that distance. All these years they’ve remained absorbed in it and all it represents, and now I see how ready they are to let it go and move on.

The next morning my parents receive word that the closing will be at 3:00 PM—it’s really going to happen. Doubtful that this day would ever come, Dad isn’t quite ready. She asks me to help retrieve the remaining larger items she wants to save: a wall-mounted cabinet from cabin number nine and a tall set of shelves from cabin number five. The new owners are going to get rid of it all, and Dad can’t bear to leave “good units” like this behind. As we pack the items into her truck, I realize this is the last time I’m ever going to work alongside my father at the motel, and how much that work, and this place, have shaped who I am. It makes me stop and draw in a breath, stunned by the finality. I look all around as if, along with my breath, I can hold the image of the motel exactly as it is now. Then it’s time to go.

Dad is the only one who needs to be at the closing, so Mom drives me to the train station. Only twenty-four hours ago I was arriving, and now I’m returning home, to my own life. It’s a relief. This visit has been heavy, but I’m glad I came. I wanted to honor my time at the motel with a proper goodbye. It seemed only right; the place has taken up so much space in my mind that I wrote a book about it. Maybe someday I’ll even get it published. It would be nice if the motel could live on in some form, since it won’t be there on the side of Route 9 in upstate New York, where it’s been all my life and longer.

On the drive to the train station Dad calls us: It’s done. The papers have been signed and checks handed out. The tenants who still live on the property will have a few months to vacate, and then the new owners will start demolition and eventually construction on the senior housing units that will take the motel’s place. At least it will still be a home of sorts, I tell myself. Better than a gas station or storage facility.

At the train station Mom and I get out of the car and hug. “Congratulations,” I tell her. “You’re free.” She squeezes me tightly, like always. “It doesn’t feel real yet, but I’m happy it’s over.” I’m happy for her. Her life is wide open now, as is mine. My parents worked hard so that it could be.

On the ride back to the city it starts to sink in, as I gaze out the train window at the smooth, gray water of the Hudson. The motel was the birthplace of my family, the place where we became ourselves. It was also one of the last bonds shared by my parents; now, with it sold, they can continue drifting apart. There was already no going back to the time before Dad’s transition, but the sale of the motel feels strikingly permanent. If we can never return to the place where it all started, how can we ever return to each other?

This fear continues to grip me even as I go home to my own family and resume the life I’ve made for myself. I know this fear is fruitless. All I have to do is look at my son, growing and changing by the day, to know that life doesn’t languish; it moves ever onward and takes us, willing or not, along with it. This, I remind myself, is a good thing. Without leaving home as a teenager, I never would have created the life I have now. And without shedding the man she used to be, Dad never would have become the woman she really is.

The motel, too, is on its own path. A few months after the sale Dad sends photos of the motel with the cabins removed and shares good news: Rather than being destroyed, the cabins have been relocated to a preserve near the Vermont border, where they’ll be fixed up and rented out to people looking for a peaceful riverside getaway. It’s a shock to see the property so empty, returned to its pre-motel state. Mom says something about the cabins getting a new life at the preserve, and it echoes the way I always thought of them when I was a kid: like they were somehow sentient, stoically observing us in our busy human lives. Mom suggests that we take my son to stay there someday, and I agree, wondering if the little structures will remember us, if they’ll be content in their new home, and how many more people will cross their thresholds in whatever time they have left here on Earth.

In the meantime, I have the photos I took of the motel on that fall day before the sale, my favorite being the one of the disintegrating pickaxe and shovel—tools finally released from their duty and free to become something new.

Katie McDonough is a writer and editor with a background in book publishing and literary nonprofit work. In her current job as a literary speakers agent, she represents writers for their readings and speaking engagements. Katie’s work has appeared in A Women’s Thing, Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood, Used Furniture Review, and other publications. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from The New School and lives in Brooklyn, New York, with her husband, son, and pet rabbit. Visit her at katie-mcdonough.com.

Matt Bollinger received his BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute in Painting and Creative Writing and his MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in Painting. His work has been exhibited in solo shows in New York, Dublin, London, Paris, Los Angeles and elsewhere. He is represented by mother’s tankstation and François Ghebaly Gallery. He lives and works in New York State.