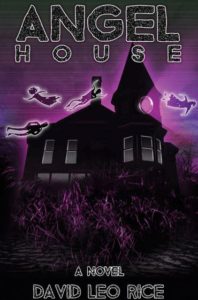

An Interview With David Leo Rice

David Leo Rice is a Brooklyn-based writer whose second novel, ANGEL HOUSE, is due out this June. In this Weird Fiction extravaganza, readers will encounter the Town, a mythic gathering place for spirits floating upon an inland sea. In this strange yet familiar place, two friends come-of-age as they try to turn their ultimate fantasy, a Pretend Movie, into a real film. Meanwhile, a sinister force named Professor Squimbop tries to educate the Town’s children on Death, videotapes open otherworldly portals, and a radio announcer levitates children with the power of his voice.

David Leo Rice is a Brooklyn-based writer whose second novel, ANGEL HOUSE, is due out this June. In this Weird Fiction extravaganza, readers will encounter the Town, a mythic gathering place for spirits floating upon an inland sea. In this strange yet familiar place, two friends come-of-age as they try to turn their ultimate fantasy, a Pretend Movie, into a real film. Meanwhile, a sinister force named Professor Squimbop tries to educate the Town’s children on Death, videotapes open otherworldly portals, and a radio announcer levitates children with the power of his voice.

LIT Prose Editor Joshua Lemay sat down to talk with David about the book, his process, and his relationship with the surreal.

LIT: Thank you for sitting down with me. As I’ve come to expect from your work, ANGEL HOUSE is a wild, mind-bending ride. When did you first start working on this book? Was there a central theme or experiment you wanted to explore?

David Leo Rice: This book had a long gestation. I started writing it after I graduated college in 2010. That fall I had a fellowship where I got to spend a year in Berlin. I knew I wanted to write a novel, and I’d been reading a lot of William Faulkner and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, so I really wanted to do an epic about Northampton, my hometown in Massachusetts. Magical realism is almost a historical term now, but I wanted a contemporary magical realist account of my town as a mythic site.

The seed of the idea was to turn the feeling I had in the town as a teenager into something that could exist in the adult world. In that way, I was putting myself through the same process the characters in the book are going through, which was an interesting limbo of both empathizing with the characters and trying to not be like them, as in finishing something the characters can never really finish. That was the experiment of the book—to fully express where they are coming from without being them.

LIT: And in that regard you’ve succeeded, as we have the final product. Now, your first novel, A Room in Dodge City is told entirely in vignettes, while this book is a more contiguous experience. Am I right in assuming this novel was your first attempt at a longer form of storytelling?

DLR: Almost. Dodge City came out of my first draft of ANGEL HOUSE, as did a bunch of short stories. This was really the first book I was determined to finish. I set myself that goal as soon as I started. If I didn’t finish this book, I’d never finish anything else. Putting that pressure on myself was hard, but I think it was a crucial phase of development. I had to go through it to even, in my own mind, learn what a book was.

LIT: Which is to say learning what a book is from the storyteller’s perspective?

DLR: Yes. If you grow up reading books, you’re obviously aware that they end at a certain point. To write to the end of a book is a different thing. In my experience, you can approach it as a potentially infinite project, which is sometimes necessary if you want to fully do the best thing you can. However, that thinking is dangerous because the project has to become non-infinite.

It’s an irony in the sense that, when you’re younger, there’s a fear you might never do anything else, so you put every idea into one thing, which makes it more likely you won’t do anything else. You keep yourself from finishing.

LIT: How did that struggle manifest for you during the first draft?

DLR: I couldn’t go back and read the draft at all. I didn’t know how yet. I had to go forward and could only be totally immersed in it. I wasn’t seeing it as a text—it was only an experience. The revision was turning that journey into a book.

That first draft was something like fifteen hundred pages, around a million words, which has been completely cut down and reconstructed. I think that first draft was what William Burroughs called “The Word Horde,” and I broke that horde down, which was necessary for me.

Working on a lot of things at once has been worth it, but it was a painful process and a brutal revision. When I revise now, I don’t cut eighty pages at a time like I had to with this.

LIT: That sounds brutal, but it also sounds as though the experience taught you a lot.

DLR: Definitely. I learned to revise with the faith I was going somewhere, that eventually I would go from process to product. I also got more comfortable reading as I went along. You can see what you’re doing, which gives a more fluid back-and-forth between reading and writing, and therefore between idea and book.

You can find important clues strewn throughout a draft and finding them is related to reading. The better you are at reading your own work, the more you can trust your own taste. You can become a relatively reliable barometer of your work, which lets you see what’s latent in your drafts and what you can bring to the surface.

Now, when I start a book, I can see the full shape of it, which makes the process a lot easier, but there is a bittersweet quality. A book feels like one thing among many now. It’s no longer an experience of complete immersion, whereas working on ANGEL HOUSE really felt like the end-all. I guess that’s kind of a disenchantment. I no longer have the sense a book could be a life project, and I’ve never again had the experience of being that invested in something.

LIT: In that regard, the novel must be very personal, especially if you were writing it away from home.

DLR: It is my most personal book. I wrote it in big cities like Berlin, Boston, and New York, and while reflecting on the town, I found a longing for each place from the perspective of the other, but I could never be in both at once.

Maybe the condition of literature is you can’t be writing about the situation you’re in. You have to find a way to be non-redundant, and you can do that by drawing yourself away from where you are, toward where you want to be. I don’t mean a place for wish fulfillment, but a place you’re thinking about for some reason, even if it’s a dark place or a place you fear. Something in your mind has to be different than the site you’re actually writing in.

It is also a coming-of-age novel about my teenage years that I developed over the course of my twenties, and the idea of decades is important in it. You see each character at nine, nineteen, and twenty-nine, each on the cusp of the next decade.

LIT: You also began this novel at the turn of a decade, during which a lot of political transitions and resentments have occurred. How much of the book would you say is a product of that climate?

DLR: I didn’t anticipate it, but the book is a product of those years. The Town itself is all men, and there is a regressive, atrophied masculine quality to it somewhat tied to an anxiety about the end of history. It’s a Town where nothing new can happen, and so it turns to various kinds of fetishes and obsessions. There’s a bitterness which I feel is the area we’ve arrived at—it’s hard to have an optimistic sense of a productive future.

A lot of dark political trends seem tied to either reenactment of an idolized past, of which MAGA is an example, or to a nihilism that just says fuck it all. There’s also a descent into fantasy, whether it’s video games or porn—these various technologically mediated worlds that aren’t a form of human contact. All of that is flowing through this book. I wouldn’t say it predicted anything, but it is a symptom of something that is undeniably present in the world.

LIT: You take a lot of that virtual anesthesia and give it a literal space in this novel. Meanwhile, the kids have their Pretend Movie, which they find impossible to complete. In that sense, the book deals with a lot of people who might have a vision that drives them, but they never seem to reach it.

DLR: That’s why coming-of-age and the cusp of adulthood is so important. The theme of a Pretend Movie versus a Real Film is a source of real anxiety to me. My emotional balance is on the side of the children, and their Pretend Movie is a pure vision of a great thing—it’s this sort of religious, emotional, and imaginative realm—but a problem comes when you’re twenty-nine and still stuck in the Pretend Movie.

You’ve moved into this dark place where you can’t offer anything to society, which is often when you become bitter. A lot of the dark forces we see today are probably people who have something to offer but haven’t found a way to offer it.

I would also add that moving from the Pretend Movie into the cynical, industrial world of film is a fall from grace, but it’s also a necessary thing because time moves on. That’s part of the negotiation of making something, rather than being a dreamer.

LIT: Speaking of film, the book deals with movie-making more than any other art form. What is your relationship to that genre?

DLR: Film is a crucial obsession of mine, and I think writing a novel is very close to directing. The process is obviously different, but your goal is to flesh out a complete world, which I find more satisfying than a script. A script is closer to architecture in the sense that you need someone else to direct and build the world. In that respect, this book is an attempt to create a kind of film that couldn’t exist for financial and logistical reasons.

I’ve always had this anxiety as to working in literature or film. I do a lot of animation, which is a writer’s way of making a film because you can do it on your own. I think all writers are on some continuum between filmmakers and poets. I put myself on the filmmaker side, where you start with an image or scenario, the atmosphere, and then put that into words. Poets would be the other extreme, where you start purely with words and then work to form something that has a look and a sound. I care about language, but it’s always second to the image. I don’t think of things in words first.

LIT: The novel also opens with a dedication to Northampton’s Pleasant St. Video, which immediately puts film in the mind of your readers. Could you tell me a little bit about that store?

DLR: That store was kind of a religious, holy site in Northampton. I would say the two holy sites of my childhood were the bookstore and what I called the movie store. I almost picture them in a vertical hierarchy, where the bookstore is the surface level. It smelled like coffee and was full of daylight. There was something above-ground about it, whereas the movie store, which did have a downstairs level, was much more subterranean.

When I was a kid, the movie store also contained the taboo with all these movies I wasn’t allowed to see. I always looked at the pictures on the back of the boxes and tried to imagine a story. I could glimpse at the forbidden world, but not enter it and, in a way, I wanted to write a book that takes place in that world.

I think those two places, that combination of above-ground and below-ground, are the aspects of my literary heritage. My own stylistic development is an attempt to write, in an elevated style, about depraved and basement-dwelling things.

LIT: On that note, a lot of the depravity in your work holds a strange, surreal twist, and I often see the word “Surreal” applied to your work. How do you feel about that as a label?

DLR: I also struggle with the right word. Horror doesn’t really fit. Magical realism might if it wasn’t tied to the 1960s…so surreal is okay. My goal is always to marry the outlandish and the bizarre with this very emotionally grounded space.

I often think of it as two axes, an X and a Y for Strangeness and Sadness. Your goal is to never be on one or the other, but to be somewhere on the plot of the two. Strangeness without sadness is weirdness for its own sake, a kind of zaniness, while sadness without strangeness is like American Realism and Raymond Carver, which doesn’t really speak to me. I can see why it’s considered good, but I’ve never wanted to take after that. I want an emotional impact in a dream world.

LIT: I imagine there are some who aren’t as willing to go into a dream world to find that impact, or who want answers to all this strangeness. Do you worry about reader accessibility?

DLR: I strive to be accessible in an emotional way, though I understand it poses some challenges to people. However, I do feel delayed gratification is a good thing, while withheld gratification is not. My work shouldn’t be the kind of thing without a pay-off or have infinite interpretations. That doesn’t hold me. I want something that functions as a story.

A goal—especially in this book, which is so much about childhood and adults who haven’t moved past childhood—is to offer adults the feeling a child might have while reading a fairy tale, which is very different than an adult reading a fairy tale. The fictional world might be deformed and influenced by subjective experience to degrees, but to have that pay-off is important.

LIT: While working in that strange vein, have you written anything you consider too unsettling or perverse for publication? Is there a line?

DLR: There’s only a line in terms of not having an emotional register. I’m not interested in writing that’s just sadistic or gross. I like to see how far I can take someone without losing them. If I don’t think anyone would go to that place, or I couldn’t get anyone there, I won’t do it. You don’t want to throw a party no one would come to, but you can get some people to attend a really bizarre party.

I also find my own discomfort is a valuable barometer. I write things that are much stranger than I am, so if I can make myself slightly uncomfortable, but still understand what I’m doing, then I feel like I’m in a productive zone.

LIT: What do you find to be the biggest threat to your own productivity? In other words, what do you struggle with when you sit at your writing desk?

DLR: Distraction. It’s hard to be riveted in one headspace, but there’s also a question of which distractions are good, and which are bad.

If you’re trying to be a writer in the 21st Century, you know the reading experience is going to be fragmentary. The idea that you’re going to write a singular thing that someone will read in a twenty-hour block doesn’t describe a real experience in the world. You can comment on fragmentation by tapping somewhat into your own attention, but there’s obviously a point beyond which you’re so fragmented nothing can get done. It’s a question of how to make a broken-up map of experience constitute a story.

The goal isn’t to be a monk. I want to be in the world and on the internet, and I don’t want to withdraw from that, but I do want to say what is psychologically scary about this. Can I keep a coherent consciousness to even say that much? I think about that a lot.

LIT: And what about the writing process drives you back to your desk, day after day?

DLR: It shows you a lot about yourself. I don’t think you can write something about what you already think. You can only write if you are genuinely trying to figure something out. You might never figure it out, but it’s good as long as you’re trying to think in a sustained way. I’m grateful for the writing process because it’s also a learning process.

I also have a sense that writing is the only thing I can offer. Being kind and being decent is important, but if I can offer the world anything special, it’s going to be a writing project. There is no other realm in which I could make a meaningful and useful contribution.

In that way there is a desire to keep writing. Wanting to do it and knowing I can succeed is a good feeling, but there’s also a fear about not doing it—What would I do to myself if I didn’t go back to the desk? I think you need that dark double if you want to get yourself to do things.

It’s almost like a father and a son. The father says “You have to do this now,” and it’s not negotiable, but there’s also that childish side of playing around and seeing where your attention goes, of being open-minded enough to take on different ideas.

If you can count on yourself to do it, if you have that rigid side where no excuse is valid, then, in my experience, you feel good about yourself. I feel like someone fit for the world.

LIT: I think a lot of writers can relate to that. By way of wrapping up, I wanted to ask you what’s on the horizon. I know A Room in Dodge City Vol. 2 is forthcoming in December, with a Vol. 3 after that, and you have a novella called Emergency Hotel with some publishers.

DLR: Yes, all those should be coming out within the next year, if possible. There’s also a novel called The New House, which is about a reclusive sculptor based somewhat on Joseph Cornell. He’s one of whom I call The Basement Boys, and that whole world fascinates me. The book is basically the fictional version of that article.

The thing I’m working on now is called The Berlin Wall, and it’s the first story I’ve done set totally in Europe. It takes a version of German History, in which the Berlin Wall became a conscious, living entity. After it was broken, all the pieces walked away and became semi-human. The book itself takes place in the present day, where the German government categorically denies the story, to the point where anyone who talks about it is labelled a Soviet nostalgist.

I’m trying to apply a weird fiction lens to real events and the echo chamber of history. It’s dangerous to be too topical, but I’m interested in using actual history as fodder to tell a mythic story. I think if that book has a moral—which is also a dangerous thing to say—it’s about finding a non-fascistic way to integrate mythic thinking into modern life.

LIT: There’s a lot to look forward to. Are there any final thoughts you’d like to add?

DLR: Having this book out is an unbelievable relief. I was very much picturing myself buried with it. I don’t know what the future will bring, but I’m fairly certain this is a unique feeling. I’m not sure I could ever put that much into something again.

It’s maybe true for a lot of people that their first book is, in some ways, all their books. Everything is an offshoot of that. There’s only one trunk and everything else is a branch. ANGEL HOUSE is definitely the trunk.

*

Bio:

David Leo Rice is a writer and animator from Northampton, MA, currently living in NYC. His stories and essays have appeared in The Believer, Catapult, Black Clock, DIAGRAM, The Collagist, Fanzine, and elsewhere. His first novel, A Room in Dodge City, was published in 2017, and its sequel is forthcoming in 2019, along with ANGEL HOUSE. His work is online at: www.raviddice.com

© LIT Magazine Issue #33, 2019