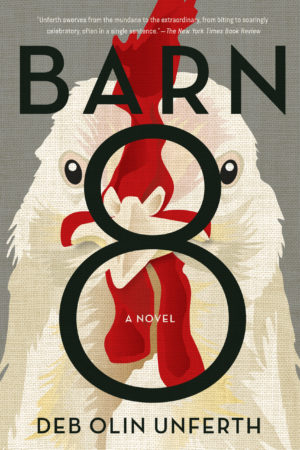

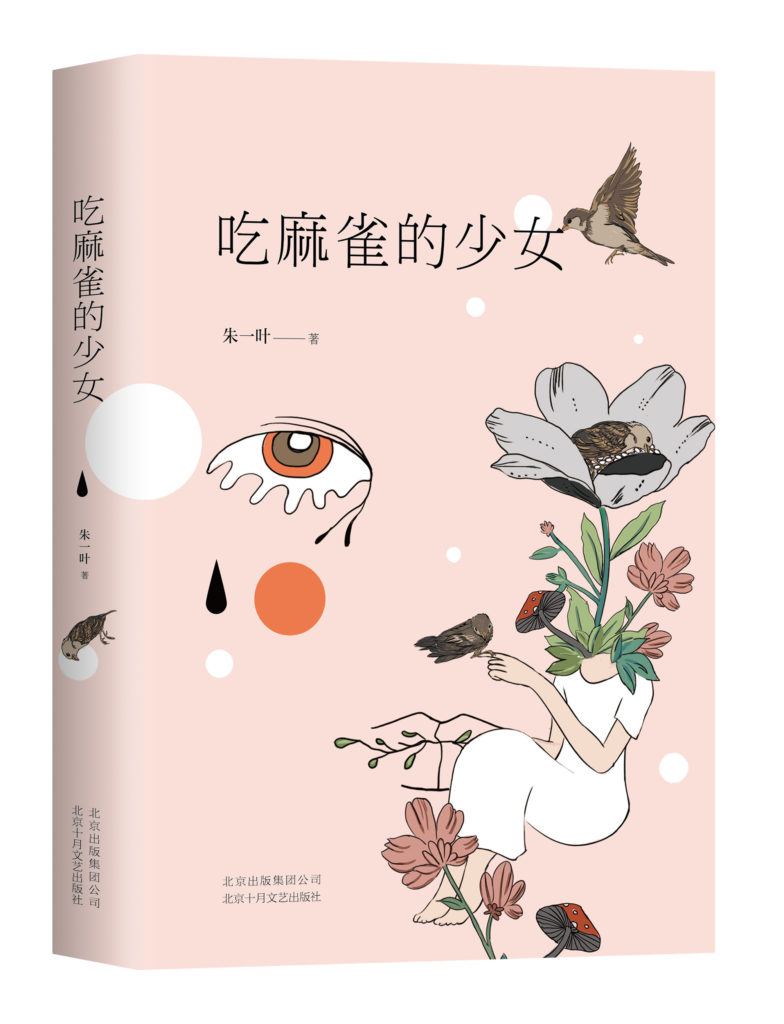

"A Girl Who Eats Sparrows" excerpt from a novella by Zhu Yiye (translated from the Chinese by Liuyu Ivy Chen) Photography by Yi Xin Tong

A Girl Who Eats Sparrows

Introduction by Liuyu Ivy Chen

In these first two chapters, a group of men are drinking, eating fried soybean worms, and recalling their youthful days during the Vietnam War with disturbing detail. While their wives are excluded from the room, their small children play around the table and quickly pick up the battleground language—they begin a killing game to mimic the war glory, craving the thrill. The adults offer no explanation or guidance to help the children understand the brutality of the war—they don’t seem to understand it either, enabling their pain to grow violent towards women, children, and animals. Zhu Yiye draws the reader into these visceral vignettes of an abused childhood in a middle-class household, alluding to but not naming what it is that bugs the psyche of the Chinese people. Naming carries the danger of excluding the nameless, the uncertain, and the unknowable. She plants hints—The Vietnam War, the one child policy, the reform and opening, and other historical events in contemporary China—revealed under the children’s innocent gaze and recreated in their playful hands. In a sense, the adults are just children in larger sizes, and the world is a giant children’s playground. In subsequent chapters, the heroine meets two friends who believe their dead fathers have reincarnated into sparrows flying back to visit them. ‘Sparrow,’ therefore, becomes a spiritual symbol, bonding their friendship. On the heroine’s birthday, however, her father forces her to demonstrate how to eat fried sparrows—her friends’ missing ‘fathers.’

1

My mom always adds a lot of salt when she cooks; I know it’s a trick. I’m short and skinny; clothes bought two years ago still hang loosely on me. I lick my palms—fishy and salty, the nauseating taste of cured meat.

It’s Thursday morning. Mom throws a burnt, salt-covered fried egg onto my plate. “Too salty,” I say. She slams a pot onto the stove, grabs my plate, and dumps the fried egg into the trash can––her action swift as though she’s been rehearsing it for a long time, just waiting for my words. She wipes her hands on her apron and sits down, letting tears roll down her deadpan face without making a sound. I see the tears gather at the tip of her nose before they drip onto the plate of steamed buns in front of her. The buns must be soaked in tears, too salty to eat, I think.

She’s always like this, a frail and sensitive princess, weeping over trivial things, using her tears as a weapon. She has a thin neck and likes to wear turtleneck tops, often with her chin tilted up slightly as her eyes look away—I almost never see her pupils at the centers of her eyes. Two light-brown tear streaks linger under her eyes even when she’s not crying, like dry riverbeds in the desert. These two tear streaks set the tone of her facial expression, making her look perpetually sad and distant, and betraying her true nature even when she laughs aloud––like a hysteric monster that might burst into tears at the next second.

I imagine Dad would notice everything soon. He’d stuff half of a salty-wet steamed bun into his mouth and holler in a slur, “Stupid brat! Pissing your mom off again?” I’d steal a glance at Mom. Her fingers would gently glide over her cheekbones to block the two sad rivers; then she would sniff, lifting her head slightly to look toward the green fridge. Before I could come up with an explanation, my silence would further enrage Dad and I’d have to hold my breath, clutch my shoulders, close my eyes, and squeeze my face into a wrinkled walnut as his right palm flies over—a loud slap, and my face would turn red hot as if smeared with chili pepper.

But what happens this Thursday morning is a little different than usual. This time, when his palm flies over to meet my face, I successfully dodge it, and the angry palm whips past the top of my head, a cool breeze rousing a few strands of my hair. Glad to have escaped a blow, I beg loudly: “It’s my fault! I won’t do it again!”

Mom stands up to make more eggs. She fries an extra egg for Dad. When I leave home, I even see Dad holding Mom’s waist with both hands. They look into each other’s eyes, whispering about something. They aren’t usually this intimate. Most of the time, Dad yells with rage, his saliva spraying madly in the golden sunlight, while Mom quietly sheds tears in the shadows to the side. I find myself not totally useless in contributing to my parents’ happiness.

I think Dad’s crankiness probably comes from his appetite for wild animals. Fried grasshoppers, cicadas, silkworm pupae, soybean worms, and little birds often appear on our dining table. He uses a long stem of grass to pierce through the seams behind live grasshoppers’ heads––from afar, the heavy kebab looks like a peculiar necklace belonging to a primitive man. The naïve grasshoppers kick their bristled thighs and wave their antennae in slow motion, as if they’ve suddenly forgotten where they are and the fact that they’re dying.

Every weekend, Dad puts on his rubber boots and camouflage uniform to go fishing in the river. Our fridge is ready to burst with the accumulated fish of different sizes. Sometimes, when I open the upper freezer door, a big chunk of frozen fish would tumble out and hit the ground. I hate the white-colored fish fillet, the white-colored fish eyes, and the endless fish bones. The yellow-colored fish roe is the most delicious, but Dad says it’s not good for kids because eating the “numberless” fish roe will turn me “number-blind” when I grow up. I can only watch my parents eat up the roe. I’m most fascinated by the fish’s swim bladders because every time Dad cleans fish, among the puddle of blood and guts, he theatrically stomps on the swim bladders, which loudly explode into a bloody pus that sprays everywhere. I scream and giggle in excitement. Dad says the swim bladders allow fish to navigate up and down in the water. Although I’ve never been under water, I have no doubt that I can swim because I’ve eaten countless swim bladders. Like balloons, they are difficult to chew, so I swallow most of them whole.

Besides frequently targeting fish in the river and insects in the woods, Dad also occasionally catches hares, frogs, pheasants, mallards, and all kinds of birds. I can see a lovely brown rabbit with two vigilant ears standing erect; sunlight shines from behind, turning its ears a semi-translucent pink—I can even see the blood vessels inside, which look like an intricate traffic map. Before I have time to pet the rabbit or feed it a blade of grass, Dad grabs it by its ears and throws it hard against an iron railing—it’s instantly killed, its limbs falling limp. In no time, it becomes a pile of brown hair and a heap of a bizarre creature with huge eyeballs and pink muscles.

As for small chores like slaughtering chickens, ducks, and small birds, I’ve seen way too many—the method is more or less the same. I’m familiar with every detail and every step; if given a chicken, I have no doubt I can give it a clean kill. When I have insomnia, I count chickens instead of sheep. One, two, three… hundreds and thousands of them pacing around in my head, shaking their feathers, revealing their creamy third eyelids when they blink, and tapping around with their sharp beaks, until I fall into a dream as bright and brittle as congealed chicken blood. In my dream, I have disproportionately large hands, a resounding voice, enormous strength, and a brutal temperament—enough to crush almost anything.

But Dad never gives me a chance. I think he enjoys a great deal about the killing process. Every step of the way, he turns to me and lectures: “See? You must grab it this way!” He uses his left hand to grip the chicken by the roots of its wings while locking its head down with his left thumb, leaving the chicken kicking its claws through the air in vain.

I squat on the ground, my arms fixed between my knees, my body rocking back and forth. Dad would continue only after I nod earnestly. He uses his right hand to pluck a few pinches of feathers from the chicken’s front neck, revealing a small patch of skin. He then reaches his hand in front of me, motions to the right with his chin, and makes an erm sound. I understand that he’s signaling for me to hand him the knife. I’ve been waiting for this glorious moment for a long time. I rush to pick up the heavy knife from the ground, as if fearing someone would beat me to it. But since I’ve been squatting, when I stand, I can’t feel my right foot, as if it’s planted in a soft cloud. My body shakes and the knife nearly cuts into Dad’s forearm.

“You stupid brat!” He grabs the knife and waves it at me, before he aims it at the chicken’s neck, and slits it open. “Your hand must be fast and exact!” He sounds harsh and merciless, as if I’m the daughter of a butcher and will one day inherit the family business.

I know when this chicken will stop flapping its wings and can almost predict when its claws will stop jerking. I hold my breath in concentration, waiting for the tranquil moment when the last drop of blood drips into the bowl—what a relief.

“Look, there’re a few small eggs inside this hen’s tummy.” Dad is cleaning the chicken’s bowels now. He beams. “Guess how many? If you guess right, they’re all yours!”

I know those chicken eggs, undeveloped like a mound of differently sized orange ping pong balls. “A thousand!” My excitement tends to turn my words into gibberish.

Dad gives me a stare and continues cleaning the chicken crop. This is my favorite moment of killing a chicken. He opens the crop carefully, as though unwrapping a gift box, full of anticipation. We inspect its contents closely and identify a few bits of gravel, grass seeds, and minced insects—as if we’re studying the chicken’s life story.

I’ve never had such a strong desire to understand a chicken as I do now. I respect it, care about it, and try to follow these traces inside its crop to reconstruct its life before it met my dad. I imagine it pacing through the woods, pecking grit now and then, and swallowing some delicious, fat worms. I imagine it meeting a brilliant rooster with a shaking red comb and oily feathers. I even imagine a future when these unhatched eggs become a flock of lovely chicklings with soft hair enveloped in sunlight, leaving strings of sweet sounds as they stumble forward like a golden shadow spilling out on the ground before their mother.

I like these moments when Dad and I are huddled together, my head touching his head, my shoulder touching his arm. I can feel the heat of his skin and the damp, hot breath from his mouth. He even helps me scrape a little congealed chicken blood off my forearm. We fiddle with the chicken crop’s smelly insides, lost in our separate fantasies. Although it looks a bit odd to others, it’s nonetheless a rare moment of filial intimacy for us.

2

This weekend, several uncles visit our home. They are Dad’s army comrades, wearing green uniforms for the gathering. Two of them bring children. One is a cherubic boy called Baobao, who has a snub nose and a curled upper lip, making him look as though he’s unable to shut his mouth. His cheeks are so red they look almost purple. The other child is a girl named Doudou, who wears a pink dress, white stockings, black leather shoes, and two pigtails tied with big pink butterfly rosettes. Doudou holds an ugly, electronic talking doll that not only has the same hairdo as hers, but also wears a near-identical outfit, as if it’s a miniature Doudou, a dozen times smaller. Both Baobao and Doudou are a few years younger than me, but Baobao’s body is larger than Doudou’s and mine combined.

Looking embarrassed, Doudou’s dad greets my mom: “She insisted on coming to play with sister Fangfang.”

Mom serves drinking water to the guests while trying to put on her typical, awkward smile. She bends down to ask Doudou, “How old are you?” I remember she asked her the same question last time. If I’m not mistaken, she would ask this question to all children.

Doudou stands straight and speaks word-by-word as if answering a teacher’s question: “I am four years old!”

But nobody cares how old she is. The men greet each other and sit down at the dining table. Mom’s smile soon disappears into the two dry riverbeds under her eyes. She turns and drifts off into the kitchen.

The red-faced Baobao and I jump madly on the couch. This cream-colored, flaking, faux leather couch can hardly bear our weight, creaking in agony. Dad would not risk losing face to lash out at me when his guests are over; it’s my great opportunity to do whatever I please. I like these uncles visiting my home. The adults talk, laugh, drink, and play finger-guessing games, while Baobao and I scream at the top of our lungs, trying to drown out their voice. Baobao and I quickly become allies, stopping Doudou from climbing up onto the couch—as soon as she emerges, I kick her off. Baobao jumps and gulps for air. His laughter is strange, sometimes sounding like a snorting pig; his big breasts and belly bounce up and down. Doudou wallows on the ground, wailing. Her electronic doll lies face down, as if out of control, repeating a nursery rhyme: “Two tigers, two tigers, run fast, run fast.”

We soon grow tired of jumping on the couch. Like three tenacious flies, we chase each other around the dining table, our sticky black hands grabbing at the adults’ neat green uniforms. I persuade Doudou and Baobao to act like two little dogs trotting under the table while I, their master, throw a chicken leg from the dining table at them as they bark nonstop. I get down on the floor to correct Baobao with strict orders, because he looks more like a pig than a little dog. This game doesn’t last long, but soon ends with Doudou’s siren-like wailing. One of the uncles, at the height of a passionate speech, stamps his foot on Doudou’s small hand. Doudou’s dad pulls her out from under the table and puts her on his lap, but Doudou is no longer the little princess she was when she first entered the door. Her hands are black and greasy and her face isn’t any better; her white stockings have been torn, leaving two big holes at the knees; a butterfly rosette has fallen apart, with a pink ribbon hanging down on one side––she looks like a pathetic little beggar. As soon as she’s seated on her dad’s lap, she cries even harder. In a fluster, her dad mutters, “Oh, Oh, Doudou’s good. Don’t cry. Don’t cry,” while shaking his legs, as if comforting an inconsolable infant.

The tallest uncle tries to continue his conversation that seems to concern sugarcane. “In Vietnam, sugarcane grew everywhere on the roadside—” He starts like this a few times, but Doudou’s crying cuts him off every time. He raises a wine glass, pauses for a while, scratches his head, and forgets what he wants to say. He then empties the glass.

The men fall into silence, staring at the siren Doudou’s dad is holding, not knowing how to comfort her. I know what my dad is thinking, with his narrowed eyes. Every time he sees a child like this—rolling on the ground crying for things to buy, talking back to his parents, acting naughty, disobedient, or making mistakes—he yells furiously to himself, “Spoiled brat, beat him up! Give him a big slap on the face and he’ll behave!” Dad will then glare at me, giving me two slaps in the air. I’ve always felt children are my dad’s real enemies. Perhaps when he went to war, he went to wipe out an army of children.

At this moment, Mom brings out a plate of fried soybean worms, our signature dish. Dad squirms on his chair, getting ready. He points at the dish with his chopsticks and says proudly: “Please come and try!” Everyone observes this plate of worms with great interest, but no one dares to move chopsticks.

Dad glances at me. I know it’s time for me to show off. Like a well-trained tiger cub, I run toward him, raise my head, and open my mouth. Dad stirs the dish with his fingers, picks out the fattest soybean worm, and lifts it up with a flourish. Wearing a mysterious smile, he shows it to everyone at the table in a sweeping motion, with his eyes moving along, as if presenting a rare treasure. Then, he lowers the worm to the tip of my nose. I know everyone is staring at me now, heating up my face and ears. I smell the fragrant fried worm and—fast and furiously—I bite it off Dad’s fingers. I can even hear my teeth mincing the soybean worm’s flesh, scaring Dad into quickly withdrawing his hand. To dramatize the visual effect, I let half of the worm dangle from my lips as I munch vigorously on the other half. A white liquid of the worm drips from the corner of my mouth. I look around and see all my uncles with gaping eyes and mouths, apparently enraptured by my outstanding performance. Even Doudou has long stopped crying, staring at me with sheer terror, as if I am no longer the thing that she used to call “sister Fangfang.”

An uncle claps his hands and declares: “Fangfang is so brave!” Other uncles nod in agreement while applauding me. The party’s atmosphere is reaching its climax.

Dad is very pleased with my performance. He waves his right hand, signaling that I can go off to play. I take another soybean worm from the plate and chase Baobao with it. Baobao screams and runs away. Doudou jumps off her dad’s lap and runs after me. We run around the table, not knowing who is chasing whom.

Mom holds a brimming bowl of fish soup and moves forward one step at a time, avoiding the rambunctious children. The fish soup laps in the bowl; some spills on the floor. Finally, she places the soup bowl safely on the table, accomplishing her mission. Then, she wipes her hands on her apron and exhales, looking exhausted. Dad grabs the adjacent uncle’s bowl, ladling fish soup for him and saying: “This is the carp I caught last week. Look at the soup—white like milk!”

Doudou’s dad says: “Ma’am, you’ve worked so hard! Please sit down and eat with us.” The other uncles echo this sentiment, sliding over to leave a space next to Dad.

Dad hastily says: “No, no, she can just eat in the kitchen.”

Mom squeezes out an elusive smile, using the last strand of her strength: “Enjoy yourselves. I’ve left some food in the kitchen. Don’t worry about me. I’ll go get some rice for the children.” She then floats back into the kitchen.

We stand next to our dads, holding our rice bowls and wolfing down the food. The three of us have been playing all morning and now we’re starving. The uncles drink and chat on and off, but rarely touch the food; their talking and blinking slow down as their eyes turn sluggish. If you stare at one of them, it’s like watching a slow-motion film. With white rice stuck to his face, Baobao raises his empty bowl and says: “I want more!” His dad immediately takes the bowl and is about to go to the kitchen for more rice when my dad stands to stop him. Dad grabs the bowl from him and hollers: “You sit down, don’t move! Little Chen! Little Chen! Come and refill Baobao’s bowl!” Dad wobbles a little; the two men look like they’re wrestling.

Mom floats out of the kitchen and tells Dad, with a gloomy face: “Don’t drink so much.”

Dad is sprawled out on his chair, beaming and grunting. Suddenly, he straightens his body up and uses his hands—as if holding a long rifle—to aim at Mom, shouting: “Giơ tay lên [hands up]!”

Mom glares at him, snatches Baobao’s bowl, and walks into the kitchen, her flip flops slapping hard on the floor, leaving a trail of noise. Other uncles wait until Mom enters the kitchen to laugh out loud.

Baobao’s dad is also fat—like father, like son. He is already balding at a young age, making us worry about the future of Baobao’s hair. He shows the most excitement, shouting: “Chúng tôi khổng hại người!”

Doudou looks up and asks her dad: “What is uncle saying?”

He explains: “We’ll spare your life!”

“What is ‘We’ll spare your life’?” Doudou looks utterly confused.

Another tall and lean uncle rolls his eyes toward the ceiling, searching his memory: “Chúng ta không, không…”

Dad follows: “Chúng ta không giết mày đâu—We treat captives with mercy!”

Doudou’s dad says: “I seem to remember how to say, ‘Don’t move.’ Is it đứng yên tại đó?”

“Yes, yes. Đứng yên tại đó—Don’t move!”

“Come, follow Dad. Giơ tay lên. Giơ…tay…lên.” Doudou’s dad begins to teach his daughter.

“Giơ…tay…lên.” Doudou looks up and spits out each word.

“Chúng tôi khổng hại người! Chúng ta không giết mày đâu!” I shout. How can I miss this great chance to show off? Dad’s been repeating these phrases since when I was little. I’ve long memorized them by heart.

Baobao is gulping down the food while Doudou and I say these strange sentences over and over to show how clever we are. The men’s facial expressions turn gloomy as they seem to have all returned to the remote, tropical battlefield: the air was damp, the woods lush, their troop ambushed. They were eighteen or nineteen. Other than memorizing several Vietnamese slogans, they hadn’t received any military training.

“First day in the trench, I was so scared my legs were shaking!” Dad cranes his neck forward, pressing his lips.

I know what he’s going to say next. “When we were charging, young comrades tripped one by one next to me. When we counted the corpses afterward, I realized they weren’t just tripping over!”

He says it just like I remember. “It was tragic!” he adds at the end.

Then comes their “killing time,” a secret name I’ve created for myself.

“I killed eight!” Dad stretches his neck further out, his crossed legs shaking violently under the table. He gestures the number “eight” with one hand, looking boastful and spiteful. He spits a lot of saliva when he says the number “eight,” which was “seven” last time. I don’t care to correct him—he adds the number every time he retells the story. One day, the number will grow to be a thousand.

“I killed three.”

“I killed five!”

“I killed a woman.”

***

Their heads come closer, their voices hushed, and their greasy faces glow under the incandescent light. They cast a wicked shadow over the dining table, like a group of conspiring murderers.

The Vietnamese phrases inspire our afternoon games. The three of us first play a hand game to decide who plays the Vietnamese, while the other two play the Chinese soldiers. We then grab whatever is at hand to use as a weapon. I take a short dustpan broom; Doudou uses her doll as a gun; Baobao—with his swollen tummy—picks up a cushion and fires “Bang! Bang! Bang!” sound bullets out of his mouth.

The rule of our game holds that whoever is playing one of the Chinese soldiers will first say the Vietnamese slogans: “Don’t move. Hands up. We’ll spare your life. We treat captives with mercy.” Then, we are free to improvise. Regardless of the other party’s raised hands or confiscated gun, we never keep our promise to treat our captive with mercy.

For instance, when Doudou and I are chasing Baobao, we shoot at him with the broom and doll, wrestle with him, pull his hair and pinch his belly until he lies motionless on the floor with his pupils rolled back and his tongue hanging from his mouth. Doudou and I cheer for our victory. When Doudou and Baobao are teamed up, it’s impossible for them to catch me, so I quickly get bored and lie on the floor with two stiffened legs, pretending I’m dead so we can move on to the next round. When Doudou becomes the Vietnamese, Baobao and I—even before we remember to say those Vietnamese slogans—jump and push her onto the floor, yanking her pigtails. I shoot madly at her chest with the broom while Baobao bashes her face with the cushion. Doudou is visibly frightened, forgetting that she could end all of this if she just pretends to be dead. She screams, cries, begs, and wriggles as we shout: “Đứng yên tại đó! Đứng yên tại đó!” But Doudou wouldn’t listen to our command. With growing excitement, Baobao and I punish Doudou—the goddamn stubborn Vietnamese—until her drunk dad wobbles over, ending our game. Baobao and I stand there, panting. I have a feeling that Doudou will never want to play with her sister Fangfang again.

The party goes on until dark. Doudou has fallen asleep in her dad’s arms, her eyes half open as if staying vigilant about her surroundings. The guests are crammed at the door, saying goodbye to my dad, shaking hands and holding shoulders.

“Let’s meet again soon!”

“Ma’am, you must be exhausted!”

“Next time, bring Fangfang to play in my home.”

“Ma’am, we’re leaving. Sorry for all the trouble.”

“Say goodbye to sister Fangfang. Say goodbye to your aunt and uncle.”

They mutter each farewell several times. After the anti-theft door is shut, our home falls into a total silence. Dad stands facing the door for a long while before he turns—as if waking from a dream—and walks back in, sinks into the sofa, and smiles with satisfaction.

Mom begins to clean the dining table. She dumps all the leftover food into the trash can without mercy—she believes food leftover from guests is full of pathogenic bacteria like Hepatitis B and Helicobacter pylori. She looks serious and moves noisily. She throws the pots into the sink and stacks up chopsticks and bowls that clang against each other. She drags a table by the corner, grating the table legs across the floor. She washes the dishes over and over in the kitchen sink, turning the faucet to the max. Those invisible bacteria drive her insane. The din from the kitchen makes me wonder if she has shattered all the dishware. But this is her way of expressing anger—she fills the entire room with her anger without saying a word. I can almost smell its suffocating odor, like the smell of sulphur after a match is lit. I breathe carefully to keep Mom’s anger from corroding my small lungs.

After washing the dishes, Mom starts to disinfect the table, chairs, couch, and floor. Every time she passes by the couch, Dad grins and reaches his hands out to grab her, or touches her legs with his toes. Mom glares at him, throwing his arms off or kicking his feet aside. Intoxicated, Dad becomes amiable, smiling as if indulging himself in some fantasy of a happy family: his wife is diligent, virtuous, and sensible; his child smart, lovely, and good-mannered; himself stable, polite, and respected wherever he goes.

Soon, Mom demands Dad leave the couch. She yanks his arms and legs, but Dad looks like jelly glued to the couch, too sticky to separate. Wearing the same smile, he even considers it fun, deliberately stretching his arms or legs for Mom to drag him off. I run over to join this rare family game. I grab his other leg and pull as hard as I can—like playing tug-of-war—but Dad’s body is unmovable. I sit on the floor and giggle. Mom drops his leg to the floor and throws the rag into a basin filled with disinfectant water, splashing dirty water everywhere onto the floor. She sits down on a nearby stool and poises herself—a pose familiar to me. The two dried riverbeds are welcoming a monsoon season, her eyes overcast as if brewing a storm; river water will soon surge to fill the riverbeds again, turning the air in the room moist and blue. Dad suddenly sobers up, wiggling his body on the creaking couch before he sits, stands, and walks toward Mom. But he kicks over the water basin and wets his feet. He curses furiously, turns, and enters the dark bedroom, throwing himself face-down into the bed. Under a dim light, Dad looks like a drowned corpse that’s just been brought ashore, water still dripping from his toes.

I also climb into my bed to go to sleep early. On a night like this, nobody cares if the sweat-stained me has brushed my teeth or showered. Nor do I worry too much about my parents, because I know they will wake from under the same comforter the next morning. I have seen this too many times.

*** *** ***

*Book cover design by artist Han Xiao*

吃麻雀的少女

朱一叶

1

我的妈妈做饭总是放很多盐,我知道这是一个阴谋。我矮小而干瘪,两年前买的衣服现在穿还直晃荡。我舔过自己的手掌,又腥又咸,一股令人作呕的腊肉味道。

就在星期四的早上,妈妈向我的盘子丢了一个撒满盐粒的焦黑煎蛋,我说:“太咸了。”她一手将锅重重地丢在炉灶上,一手将我盘子里的煎蛋倒进了垃圾桶,动作流畅得仿佛已经排练了很多次,一直就在等我这句话似的。她在围裙上擦了擦双手,坐到一旁掉眼泪,面无表情,也不发出任何抽泣声,我看见她的眼泪在鼻尖汇集,然后滴在她面前摆放的那盘馒头上,那盘馒头也一定被泪水浸湿,咸的难以入口了,我忍不住这么想着。

她总是这样,一个脆弱敏感的公主,会为各种小事流眼泪,这就是她的武器。她的脖子很细,喜欢穿高领衣服,下巴微微向上翘着,眼神总是飘向别处,我几乎没有见过她的瞳孔在眼睛的正中央。她的双眼下方即使在不哭的时候也有两道淡棕色的泪痕,我想这道理就类似于沙漠里干枯的河床,而这两条泪痕已经成为了她表情的基调,让她看起来总是悲伤,难以接近,即使在大笑的时候也会把她出卖,让她看起来像是一个歇斯底里的怪人,好像下一秒钟就会大哭起来。

我的爸爸很快就会洞察到这一切的,他会在嘴里塞上半个又咸又湿的馒头,然后口齿不清地大吼:“你个兔崽子是不是又惹妈妈生气了?”我偷偷地撇了一眼妈妈,她的手指在两个颧骨上轻轻滑过,阻断了那两条悲伤的小河,又吸了一下鼻子,头稍稍抬起,将视线投向绿色的冰箱。在我还没想好如何回答的时候,爸爸的怒气会因为我的沉默而升级,我只好屏住呼吸,缩起肩膀,在他的巴掌扇过来的时候紧闭双眼,整张脸由于太过用力而挤成了一个皱巴巴的核桃,随后就是一声巨响,脸像抹了辣椒一样又红又烫。而星期四上午所发生的一切和我预想的有一点不同,在他巴掌扇过来的时候我竟然成功地躲开了,他的手掌在我的头顶蹭了过去,一丝凉风撩起了几缕头发。我为逃过一劫而高兴,连忙大声求饶:“我错了,我再也不敢了。”

妈妈站起来又去煎蛋了,她为爸爸多煎了一个鸡蛋,在我出门的时候甚至看见爸爸用双手揽着妈妈的腰,他们对视着,又交头接耳说着什么悄悄话。他们平常并不总是这般甜蜜,大部分时间都是我爸爸在怒吼,他的吐沫星在金色的阳光中疯狂绽放,而妈妈在一旁的阴影中默默流着眼泪。我觉得自己在这个家里也并不是毫无用处。

爸爸之所以脾气暴躁,我想很有可能是因为他热爱野味。我们家的餐桌上时常出现油炸蚂蚱,油炸知了,油炸蚕蛹,油炸大豆虫,油炸小鸟……他用一根长长的狗尾巴草将绿色的蚂蚱从脑袋后边的缝隙插进去,穿成一大串,从远处看像是一个属于原始人的古怪项链,而那些蚂蚱还天真而缓慢地蹬着布满小刺的大腿,晃动着触须,仿佛突然忘了自己身处何方,也忘了死期将至这件事。

每个周末他都会穿上胶鞋和迷彩服去河里钓鱼,大大小小的鱼越攒越多,我们家的冰箱塞都塞不下,有时候打开冰箱上层冷冻室的门,就会有一大坨硬邦邦的鱼滚出来砸在地上。我讨厌白色的鱼肉,白色的鱼眼和没完没了的鱼刺,黄色的鱼子最好吃,可是爸爸说小孩吃了不好,长大以后不识数。于是我只能眼巴巴地看着他俩把那些鱼子全吃光了。我对鱼泡最感兴趣,因为爸爸每次杀鱼之后,都会在一堆血水和内脏中虚张声势地将鱼泡踩破,血水飞溅,发出巨大的爆炸声,我也会因此兴奋地尖叫和大笑。爸爸说鱼泡可以让鱼在水中自由上下,虽然我还从未下过水,却一直坚信自己很会游泳,因为我吃了不计其数的鱼泡,它们很难咬动,像在咀嚼气球,我几乎都是一整个吞下去的。

爸爸除了经常对河里的鱼和草丛中的昆虫下手,还时不时会捉到野兔,青蛙,野鸡,野鸭和各式各样的鸟。那只可爱的棕色大兔子,竖着两只警觉的大耳朵,阳光从兔子的身后照射过来,让两只耳朵变成了半透明的粉色,我甚至可以看见里边的血管,像是一幅错综复杂的交通地图。在我还没来得及抚摸它,也没来及喂它一根青草的时候,这只兔子就被我爸爸抓起两只耳朵,使劲儿往铁栏杆上一摔,立刻四肢下垂,一命呜呼了。没一会的功夫,它就变成了一团棕色的兔毛和一只有着硕大眼球,浑身粉色肌肉的奇怪动物。

而杀鸡宰鸭处理小鸟这样的事儿,我实在是见得太多了,它们大同小异。我熟悉每一个细节,每一个动作,如果给我一只鸡,我相信自己完全可以干净利索地要了它的命。在睡不着觉的夜晚,我一直用数鸡来代替数羊,一只,两只,三只……成百上千只,它们在我的脑袋里踱步,抖动羽毛,在眨眼的时候露出乳白色的瞬膜,用尖嘴四处敲击,直到我陷入凝固的鸡血一般鲜艳而易碎的梦中。在梦里,我的手和身体有着错误的比例,我的声音洪亮,力大无穷,性情残暴,几乎可以毁灭一切。

可是爸爸从来不给我机会,我觉得他在其中可以享受到很多乐趣,他每做一个动作都会扭头向我讲解:“看见了吗?必须这样抓着它!”他左手用力地抓着鸡的两个翅膀根部,并把鸡头也控制在左手,鸡只能在空中徒劳地踢腾爪子。

我蹲在地上,两个胳膊夹在膝盖中间,身体前后晃悠,直到我认真地点了点头,他才会进行下一步。他用右手在鸡脖子前边揪掉了几撮毛,漏出一小块肉色的鸡皮,然后将手伸到我的面前,用下巴指了指右边,嘴巴里发出“嗯”的声音。我知道这是递菜刀的信号,我等待这一神圣的时刻已经很久了,赶忙将那把沉甸甸的菜刀从地上捡起来,就像害怕有什么人和我抢似的。由于蹲的时间有点长,站起来感觉右脚完全消失了,就像右腿直接插在了软绵绵的云朵里,我的身子一歪差点将菜刀砍向爸爸的小臂。

“你个兔崽子!”他夺过菜刀,向我挥舞了几下,然后对准了鸡脖子一刀划过去:“下手一定要又快又准!”他的口气严厉而凶狠,仿佛我是一个屠夫的女儿,而我之后也会继承他的这份家业似的。

我知道这只鸡会在什么时候拼命扑腾翅膀,也几乎可以预测它爪子的最后一次抽搐,我屏气凝神地等待最后一滴血掉进碗里之后的寂静,那可真是令人长舒一口气。

“你瞧,这只母鸡肚子里还有几个小鸡蛋。”爸爸在处理这只鸡的内脏,他有点得意:“你猜有几个?猜对了都归你!”

我知道那种鸡蛋,它们还未成型,像是一堆大大小小的橘色乒乓球。“一千个!”我很容易将兴奋转化成胡说八道。

爸爸瞪了我一眼,继续处理鸡嗉子,这是整个杀鸡过程中我最喜欢的部分,他将鸡嗉子打开,就像打开礼物一样小心翼翼,充满期待,我们仔细辨认里边包裹的东西,一些小碎石,草籽,破碎的昆虫……就像在观看这只鸡生前的历史。

我从未像此刻一样想要去了解一只鸡,我尊重它,关心它,试图通过这些蛛丝马迹来还原它遇见我爸爸之前的生活。我想象它在树林中踱步,时不时地啄起地上的小石子,还吞下了一些肥美的小虫子,想象它遇见了一只漂亮的大公鸡,有着红色的鸡冠,来回抖动,羽毛像抹了油一样发光,我甚至幻想了未来,那些尚未成型的鸡蛋,会变成一群可爱的小鸡娃,它们毛茸茸的,被阳光包裹着,发出一串串动听的叫声,跌跌撞撞地奔跑,像是鸡妈妈撒在地上的金色影子。

我喜欢这样的时刻,我和爸爸挤在一起,我的头碰着他的头,我的肩膀贴着他的胳膊,我可以感受到他皮肤的热量和嘴里呼出的潮湿热气,他甚至帮我抠掉了小臂上早已凝固的一点鸡血。我们拨弄着鸡嗉子里散发着怪味的东西,沉浸在各自的幻想中,虽然在别人看来有点奇怪,可是不管怎么说,这都是我们难得的亲子时光。

2

周末我们家来了几个叔叔,他们穿绿衣服聚会,都是我爸爸的战友,其中两个叔叔还带着小孩,一个叫做宝宝的胖男孩,塌鼻梁,上嘴唇向上翘着,让他看起来好像合不拢嘴一样,两个脸蛋红得发紫。 还有一个叫做豆豆的女孩,穿着粉色的连衣裙,白色的长筒袜,黑色的小皮鞋,脑袋一边一个小辫,上面扎着粉色的大蝴蝶结,她手里抓着一个丑陋的会说话的电动娃娃,不但和她发型一个样,穿的也差不多,就像缩小了十几倍的她。他们都比我小好几岁,可是宝宝的体积却比我和豆豆加起来还要大。

豆豆的爸爸不好意思地对我妈妈说:“她非要来找芳芳姐姐玩。”

妈妈一边为客人倒水,一边努力在脸上展现她那令人尴尬的笑容。她弓着腰问豆豆:“你今年多大了?”我记得上次她也问过豆豆这个问题,如果我没有记错,她会问所有小孩这个问题的。

豆豆站直了身子,就像回答老师问题一样,一字一顿地说:“我今年四岁啦!”

可是根本没有人在乎她多少岁,男人们互相寒暄,围着餐桌坐成了一圈,而我妈妈的笑容很快就会消失在她双眼下那两条干涸的河床里,她转身飘进了厨房。

我和满脸通红的宝宝在沙发上疯狂蹦跳,这个早已掉皮的米色人造革沙发不堪重负,发出吃力的嘎吱声,爸爸碍于面子不会把我怎么样,这是我肆意妄为的大好时机,我喜欢这些叔叔来我们家聚会。大人们有说有笑,喝酒划拳,我和宝宝大声尖叫,试图压过大人的声音,我们很快就结为同盟,不叫豆豆爬上沙发,她一爬上来我就用脚把她踢下去,宝宝一边跳,一边大口呼吸,他的笑声很奇怪,有时候像一只猪在呼噜,他胸前的两个大咪咪和肚皮一起上下摇晃。豆豆摔在地上哇哇大哭,她的电动娃娃脸朝下趴在一旁,失控了一般循环唱着一句儿歌“两只老虎,两只老虎,跑得快,跑得快”。

我们很快厌倦了在沙发上蹦跳,像三只难以驱逐的苍蝇一般围绕着餐桌追逐起来,我们又黏又黑的脏手在大人们笔挺的绿色衣服上抓来抓去。我说服了豆豆和宝宝扮演两只小狗,在桌子底下钻来钻去,而我就是饲养他们的主人,他们汪汪叫着,我从餐桌上偷了一个鸡腿丢给他们吃,我趴在地上严厉地指导着宝宝,因为他看起来更像一只猪而不是什么小狗。这个游戏并没有持续太长时间,它终结在豆豆警报似的大哭声中,其中一个叔叔说到兴奋之处一跺脚,正好踩在了豆豆的小手上。豆豆的爸爸将她从桌子底下拽出来,放在腿上,豆豆已经不是刚进屋的那个小公主了,她的手掌又黑又油,脸上也没好到哪去,白色的长筒袜在膝盖的地方磨了两个大洞,一个蝴蝶结已经散开了,粉色的绸带耷拉在一边,看起来像是一个惹人怜爱的小乞丐。她一坐到爸爸的怀里就哭得更起劲了,她爸爸有点不知所措,一边嘴里嘟囔着:“哦,哦,豆豆乖,不哭了啊,不哭了。”一边使劲晃动着双腿,好像在哄一个毫不讲理的婴儿。

个子最高的那个叔叔刚开始还想继续他的话题,好像和甘蔗有关。“在越南的时候,路边全是甘蔗……”他这么开了几次头,都被豆豆的哀号声打断了,他举着酒杯,愣了一会,然后挠了挠头,忽然忘了自己要说什么,于是一饮而尽。

男人们都沉默了,盯着豆豆爸爸怀里那个不肯罢休的警报器,不知道怎么安慰。我知道我爸爸斜着眼睛在想些什么,每次遇见这样的情况,比如满地打滚哭喊着要买东西的小孩,和大人顶嘴的小孩,淘气的小孩,不听话的小孩,做了错事的小孩……他都会在背地里咬牙切齿地评论:“这就是惯的,欠揍,给他一个大嘴巴子就好了!”然后凶巴巴地看着我,在空中给我两个大嘴巴子。我一直觉得小孩才是我爸爸真正的敌人,也许他当年打仗就是为了消灭一支小孩组成的军队。

就在这个时候,妈妈端上来一盘油炸大豆虫,这可是我们家的招牌菜,爸爸在凳子上挪了挪屁股,蠢蠢欲动,用筷子点了点这盘菜,得意地说:“来来来,快尝尝这个!”大家饶有兴致地观察着这盘虫子,却没有人愿意动筷子。

爸爸看了我一眼,我知道登台表演的时候到了,我像一只训练有素的小老虎,迅速地跑到爸爸的身旁,抬起脑袋,张大嘴巴。爸爸用手指在盘子里扒拉了扒拉 ,捏起一只最肥大的豆虫,夸张地举到高处,和目光一起,从左到右移动一圈,面带神秘的微笑,好像在向观众展示什么旷世珍宝,随后他将这只豆虫降落在我的鼻尖之上。我知道此刻,所有的目光都集中在了我的身上,我的脸庞和耳朵因此而感觉到炙热,我的鼻子闻到一股焦香,我一口将那只豆虫从我爸爸的手里咬掉,动作迅猛而凶狠,我甚至听到了上下两排牙齿敲击的声音,吓得爸爸赶忙将手缩了回去。为了增强视觉效果,豆虫的一半身体还露在我的嘴巴外边,我使劲咀嚼着它的另一半身体,豆虫肚子里白色的浆液从我的嘴角流了出来,我环视了一周,各位叔叔都瞪大了眼睛,呲牙咧嘴的,显然被我精湛的演技所征服了,就连豆豆也早已停止了哭泣,一脸惊恐地望向我,仿佛这早已不是什么可以叫做“芳芳姐姐”的东西了。

有一个叔叔一边鼓掌一边说:“芳芳真是勇敢!”其他的叔叔也一边点头赞叹,一边鼓起掌来。整个聚会的气氛达到了顶点,热烈极了。

爸爸对我的表演十分满意,挥了挥手,意思是我可以去一边玩了。我也从盘子里拿了一只豆虫,拎着它去追宝宝,宝宝尖叫着跑开了,豆豆也从爸爸怀里蹦了下来,跟在我身后跑,我们围着桌子转圈,根本分不清到底是谁在追谁。

妈妈端着一盆盛得太满的鱼汤一步步往前挪,还要躲开这些奔跑的小孩,鱼汤在盆里荡漾,时不时从边缘溢出来滴在地上,当她将汤安全地放在桌子上之后,终于完成了任务,将手在围裙上蹭了蹭,吐了一口气,一脸的疲惫。爸爸抓起他旁边叔叔的碗,一边给他盛鱼汤,一边说:“这可是我上星期才钓的鲫鱼,瞧瞧这汤奶白奶白的,像牛奶一样!”

豆豆的爸爸说:“嫂子辛苦了,快坐下来一起吃饭吧。”其他的叔叔纷纷附和着,然后朝着一个方向聚拢,在我爸爸的旁边腾出了一个空间。

爸爸赶忙说:“不用不用,她在厨房吃就可以了。”

妈妈用最后一丝力气挤出一个短暂的笑容:“你们吃吧,我在厨房留了一些菜,不用管我,我给孩子们盛米饭去。”说完就又飘进了厨房。

我们站在各自的爸爸身旁,手捧着饭碗,狼吞虎咽地吃着,已经折腾了一上午,这让我们三个饥肠辘辘。叔叔们一边喝酒,一边断断续续地聊天,他们吃菜很少,语速越来越慢,眨眼也变慢了,目光呆滞,如果盯着某个叔叔看,就像是在看慢镜头。宝宝的脸上沾着米粒,举着空碗说:“我还要吃!”他的爸爸赶忙接过碗准备去厨房盛饭,我的爸爸也站了起来,拦着他,抢夺着他手中的饭碗大声说:“你快给我坐那儿,你别动!小陈!小陈!快过来给宝宝再盛一碗。”我爸爸有点站不太稳,他们两个看起来更像是扭打在一起。

妈妈从厨房飘了出来,面色阴郁地对我爸爸说:“你少喝点吧。”

爸爸四肢伸展地仰在椅子上,一脸得意的笑容,嘴里发出“哼”的声音。他忽然挺起身子,用双手比划成手握长枪的样子,对准妈妈大声说:“热呆连(越南语战场喊话口号中举起手来的意思)!”

妈妈狠狠地瞪了他一眼,然后气呼呼地拿起宝宝的饭碗走进了厨房,她的拖鞋和地面用力地敲打着,发出啪嗒啪嗒的响声。其他的叔叔在我妈妈进了厨房之后,才哈哈大笑起来。

宝宝的爸爸也是个胖子,宝宝和他长得很像,他还没多大年纪就谢了顶,让人很难不为宝宝未来的发型担忧。他的兴致最高,大声说着:“诺布松空叶!”

豆豆仰着脸问她爸爸:“叔叔说的是什么意思?”

豆豆的爸爸解释着:“缴枪不杀的意思。”

豆豆一脸迷茫地问:“什么叫做缴枪不杀?”

另一个瘦高的叔叔向着房顶翻着眼珠,努力在脑海里搜索:“宗堆宽洪,洪……”

我爸爸接上:“宗堆宽洪毒兵,我们宽带俘虏!”

豆豆的爸爸说:“我好像记得‘不许动’怎么说,是冷依姆,对吗?”

“对对对,冷依姆,不许动!”

“来,跟着爸爸念,热呆连,热,呆,连。”豆豆的爸爸开始教女儿。

“热,呆,连。”豆豆仰起脸一字一顿地说着。

“诺布松空叶!宗堆宽洪毒兵!”我怎能放过这个表现自己的大好时机,总共就这么几句话,我从小就听我爸爸念叨,早就烂熟于心了。

除了宝宝在大口吞咽饭菜,我和豆豆在反反复复念着这几个奇怪的句子,好显示自己很聪明以外,其他的男人都回到了遥远的热带战场。他们的表情渐渐变得凝重,那里空气潮湿,植物茂密,草木皆兵。他们十八九岁,除了会背几句越南口号,并没受过什么军事训练。

“第一天在战壕里,我吓得双腿直发抖!”爸爸向前伸直脖子,瘪着嘴说。

我知道他接下来会说什么:“冲锋的时候,身旁陆续有小战友被绊倒了,打完清点尸体的时候,才知道根本不是绊倒了!”

他几乎一字不差地说了出来,最后加了一句:“真是太惨了!”

然后就是他们的“杀人时间”了,这是我自己在心里偷偷起的名字。

“我杀了八个人!”爸爸的脖子伸得更长了,他的二郎腿在桌子下边剧烈抖动着,一只手伸出一个八的形状,他的表情又得意,又凶狠,说“八”的时候,喷出了不少吐沫,而上次他还说的是七个人。我懒得纠正他,每次说出的数字都在增加,总有一天会上升到一千人。

“我杀了三个人。”

“我杀了五个!”

“我杀的还有一个女人。”

***

他们的脑袋越凑越近,声音越来越小,在白织灯的照射下,脸上泛着油光。他们在餐桌上投下邪恶的阴影,像是一群诡计多端的杀人犯。

这几句越南话为我们下午的游戏提供了灵感,我们三个通过手心手背来确定谁演越南人,而另外两个人来演中国战士,我们随便抓起什么就来当做自己的武器,我抓着一个扫床的短扫把,豆豆将她的娃娃当成一把枪,而宝宝则抓着一个抱枕,挺着肚子,嘴巴里发出“突突突”的扫射声。

我们的游戏规则是,扮演中国战士的人要先用越南语说上那几句话,“不许动,举起手来,缴枪不杀,我们宽带俘虏”。至于接下来,就可以任意发挥了,无论对方有没有举起手来,是否缴纳了枪支,我们都口是心非,从来没有宽带过俘虏。

比如我和豆豆追逐着宝宝,用扫把和娃娃向他扫射,和他扭打在一起,我们揪他的头发,掐他的肚皮,直到他躺在地上一动不动,翻着白眼,将舌头伸出来耷拉在嘴角,我们两个才为取得胜利而欢呼。比如豆豆和宝宝一伙的时候,他们根本就追不上我,连我都觉得没意思了,只好躺在地上伸直双腿装死,好进行下一轮。当豆豆成为越南人的时候,我和宝宝甚至忘了先说那几句越南话,就直接将她扑倒在地上,拽她的小辫,用扫把戳着她的胸口疯狂射击,宝宝用抱枕向她的脸砸去,豆豆显然被吓到了,忘记了装死就能结束这一切,她大哭着,尖叫着,求饶着,扭动着,我们大叫着:“冷依姆!冷依姆!”,可是豆豆根本就不听指挥。我和宝宝越来越兴奋地惩罚着豆豆,这个该死的顽强抵抗的越南人,直到她爸爸晃晃悠悠地跑了过来。游戏就这样结束了,我和宝宝站在原地大口喘气,我觉得豆豆再也不想找芳芳姐姐玩了。

直到晚上聚会才结束,豆豆早已在爸爸怀里睡着了觉,眼睛半开着,似乎对周围保持着警惕。客人们挤在门口一一同我爸爸告别,又是握手,又是搂着肩膀。

“过几天咱们再聚啊!”

“嫂子真是辛苦了!”

“下次带着芳芳去我家玩。”

“嫂子我们走了,麻烦你了。”

“给芳芳姐姐再见,给叔叔阿姨再见。”

每一句话他们都会口齿不清地说上好几遍。防盗门关上之后 ,家里一片寂静,我的爸爸对着门口站了好一会,才如梦初醒一般转身向屋里走去,一屁股陷在沙发里,一脸满足的微笑。

妈妈开始收拾桌子,她将所有的剩菜剩饭都毫不留情地倒进垃圾桶里,因为她一直坚信客人吃过的饭菜里有着太多类似乙肝,幽门杆菌之类的致病细菌。她的表情严肃,动作很大,将锅丢进水池,将碗筷噼里啪啦地摞在一起,她拖动桌子的一角,让桌子腿和地面发出刺耳的摩擦声。她在厨房的水池反复洗刷碗筷,将水管开到最大,那些看不见的病菌让她发疯,厨房传来的激烈声响让我怀疑那些餐具早已被她摔得粉碎。而这一切都是她表达愤怒的语言,她一个字都不需要说,整个房间就全被愤怒填满了,我几乎可以闻到那种令人窒息的味道,有点像火柴擦着之后的硫磺味。我小心翼翼地喘气,防止妈妈的愤怒侵蚀我幼小的肺部。

处理完碗筷,妈妈开始对桌椅,沙发和地面进行消毒,她每次路过沙发,爸爸都会嬉皮笑脸地伸手抓她,或者用脚尖碰她的腿。妈妈狠狠地瞪着他,然后再将他的胳膊甩到一边,或者将他的脚踢到一旁。在酒精的作用下,爸爸变得宽宏大量,一直保持着微笑,仿佛沉浸在什么温馨家庭的幻梦中,他的妻子勤劳贤惠,通情达理,他的孩子聪明可爱,很有教养,而他自己则是情绪稳定,彬彬有礼,无论到哪儿都受人尊敬。

没一会,妈妈就要求爸爸离开沙发,她拽他的胳膊,拉他的腿,可是爸爸像一团胶状物,和沙发粘在了一起,难以分离。爸爸始终面带微笑,他甚至觉得这挺有趣,专门伸直了胳膊或者腿让妈妈拽,我也跑了过去,加入这个难得的家庭游戏,我抓着他的另一条腿,就像拔河一样拼尽全力,爸爸的身子纹丝未动,我坐在地上咯咯笑着,妈妈将他的腿扔在地上,将抹布丢进兑了消毒水的盆里,脏水溅了一地。她坐在一旁的凳子上,摆好了姿势,我所熟悉的姿势,那两条干涸的河床即将迎来雨季,两只眼睛如同暴雨将至一般布满阴云,汹涌的河水又将再次灌满河床,房间里的空气也因此变得潮湿而阴郁。爸爸顿时清醒了不少,在沙发里嘎吱嘎吱地扭动了一番才坐直了身体,他站起来向妈妈走去,可是一脚踢翻了水盆,水把他的脚全弄湿了,他气急败坏地骂了一句脏话,然后转身向漆黑的卧室走去,脸朝下扑倒在床上,在微弱的光线下,爸爸的姿态像是一具溺亡的尸体,刚刚被打捞上岸,脚尖还在滴水。

我也早早地爬上床睡觉,在这样的夜晚,并没有人在乎一身臭汗的我是不是没有刷牙和洗澡。我也并不为他俩太过担心,因为我知道第二天早上他们会从一个被窝里醒来,这样的事情我经历过太多次了。

*** *** ***

Zhu Yiye is a freelance writer living in Yantai, China. She describes herself as “unemployed and free.” She once carried an electric rice cooker on her back as she crossed Asia and Africa, and has recently took the Trans-Siberian Railway to cross Eurasia. Her story “A Girl Who Eats Sparrows” won first prize in the literary category of the 5th Read Douban Creative Writing Contest in China (2018). She has published two books in China: Killed by an Elephant Hoof and A Girl Who Eats Sparrows.

Liuyu Ivy Chen is a freelance writer and translator living in Atlanta. She describes herself as “a poet trying to do other things.” She recently translated Zhu Yiye’s short story “Sea Wind on a Bald Head,” published on the Los Angeles Review of Books China Channel. Her latest nonfiction “First Day of School” was published on SupChina. She received her MFA in poetry from NYU.

Yi Xin Tong is a nowhere-based artist and fisherman. In poetic and absurd languages, he uses multimedia installation, site-specific project, video, and sound to analyze seemingly desperate social conditions, and our contradictory relationships with ourselves and with other living beings, objects, and cultural entities. Exhibitions include BRIC Biennial, Guangzhou Airport Biennale, chi K11 art museum, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Long March Space, and Alyssa Davis Gallery.

Yi Xin Tong is a nowhere-based artist and fisherman. In poetic and absurd languages, he uses multimedia installation, site-specific project, video, and sound to analyze seemingly desperate social conditions, and our contradictory relationships with ourselves and with other living beings, objects, and cultural entities. Exhibitions include BRIC Biennial, Guangzhou Airport Biennale, chi K11 art museum, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Long March Space, and Alyssa Davis Gallery.