A Termination: an interview with TNS Creative Writing Professor Honor Moore about her newest memoir

by LIT Nonfiction Editors, Vicky Oliver and Sarah Persons

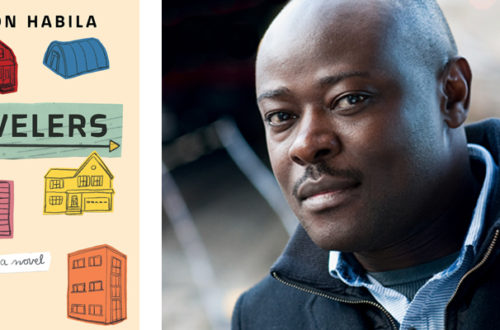

LIT nonfiction editors Vicky Oliver and Sarah Persons recently sat down with distinguished memoirist, playwright, and poet Honor Moore to discuss her new memoir, A Termination (August 2024, A Public Space). The memoir details the author’s reckoning with an abortion she had in 1969—four years before Roe v. Wade—and is told in a fragmented, poetic style. A Termination has drawn rave reviews from the New York Times and Kirkus Reviews, among others.

Vicky and Sarah first met in Honor’s “The Uses of Memory” class in the MFA program at the New School during 2022 when Honor was first drafting A Termination. Honor Moore’s other acclaimed memoirs include Our Revolution: A Mother and Daughter at Midcentury (2019), The Bishop’s Daughter: A Memoir (2008), and The White Blackbird: A Life of the Painter Margarett Sargent by Her Granddaughter (1996).

Honor Moore has also published three collections of poems and is faculty at the New School’s MFA program. She has received awards in poetry and playwriting from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council for the Arts and the Connecticut Commission for the Arts and in 2004 received a Guggenheim Fellowship.

LIT: Congratulations on the publication of your new book, Honor. Is the fragmented, prose-poem style of A Termination on account of any trauma you felt about having an abortion—either at the time or when you were recollecting it?

HM: No. There is an assumption that having an abortion is a trauma. It was not that for me. I felt isolated, yes, but I was simply relieved not to be pregnant! As for the way the book is structured, I would say that has to do with how memory comes. I remember this thing. I remember that thing. This part of the hospital. Dinner with guys. I wrote it in chunks of twenty minutes, you know, writing sessions. And I let the experience emerge and lead into further associations about it.

After Roe, when abortions became legal in 1973, there was somebody supportive to talk to you afterward. You were reassured that you weren’t crazy for making this decision. Nobody asked you in the operating room, “Are you sure you want to go through with it?” Nobody said, “You can’t tell anybody.” The anti-choice movement of the 1980s and 1990s fought that spirit and optimism with rhetoric and violence, and now, of course, all those reforms have been shattered.

LIT: You wrote: “It amazes me I didn’t tell anyone. I made the decision by myself. But also with the remote-control help of my mother. Don’t come home pregnant.” Looking back on your decision not to tell anyone, do you think it was that you were worried they would try to talk you out of it?

HM: It wasn’t my decision not to tell anyone. The doctor said I must not tell anyone. So perhaps, because I obeyed without question, it was my decision. Maybe just having the abortion was enough disobedience around the experience. I didn’t want anything to prevent me from getting unpregnant, so I did what I was told. I did not tell anyone. You said something interesting at the end of your question…

LIT: Looking back at your decision, were you worried they would try to talk you out of it?

HM: In that era being told to keep such a secret was not unusual, but I think its legacy has contributed to women’s continuing silences around reproductive freedom, which are now, thank God, being powerfully broken by the Kamala Harris campaign. Another element of my decision was that I didn’t know who the father was and that was embarrassing even in the era of the “sexual revolution.” You know, “Bad girl. Bad girl. Fallen woman. Bad Girl.”

LIT: What would your mother and father have said to you if you had “come home pregnant”?

HM: I have no idea. I don’t know what they would have said, but I couldn’t be certain they wouldn’t have had me go to one of those places and give birth and have the child put up for adoption. Mainly, I thought they would make it more complicated, more of a trauma, and less a decision I was making about my own life. I didn’t feel I had much time to argue my position, and I was not confident I could argue it. I’m the oldest of nine children and though birth control was a subject in our family—we were timed!—I never discussed the termination of a pregnancy with either of my parents until after my abortion when I announced, “You know, I had an abortion.” And then they just wanted to be sure I had been safe.

LIT: As Bishop Moore’s daughter, did you feel any guilt about your decision to have an abortion from a religious perspective?

HM: Absolutely not. This was the late 1960s and the whole world was in the process of re-inventing sexual norms. My father was progressive at the time of my abortion, a parent of the times. He had a name in civil rights and anti-war circles, but he was not yet the icon he would become in New York in the 1970s If I did something wrong, there was likely to be a conversation working through, no mention of sin. The morality and philosophy of the household was not organized around religion. All of this, I realize, is inconsistent with my being afraid to tell them I was pregnant… But we react in different ways when we are young…

LIT: When you did tell L., one of the two potential fathers, you wrote: “he begins to shout: I would have married you!” How did that make you feel?

HM: Well, I didn’t think that was how I wanted to receive my first marriage proposal. And so, I felt, you know…“That’s not good enough!”

LIT: That makes sense. You wrote: “Drive the shimmery blue Corvair forward. I worry about what’s immediately in front of me, what I can see, but I do not concern myself with what’s behind me. As for what’s ahead, I do not imagine that I am picturing the future.” Is your memoir an attempt to reconcile what’s behind you? Does all memoir serve this purpose to some extent?

HM: I think writing a memoir is, at its best, a reckoning with oneself, one’s life. I set out to write a story that I wanted to clarify. I wanted to know how this young 23-year-old woman made this decision all on her own. And who she was—I wanted to discover who she was—which I felt would help me understand who I have become, and how. When I’ve said, “I’ve written a book about my abortion,” some people say, why? But as I kept talking about the young woman I was and her decision, it all became clearer and clearer. What my purpose was, you know—the story I wanted to tell turned out really to be about a young woman becoming a writer at that time, setting herself up to live the life she dreamed of having even though I/she didn’t know then a woman could live the kind of life that I’ve had. There weren’t all that many role models walking around. Until I managed to get hold of A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf in about 1975, there was only Sylvia [Plath] who, of course, killed herself.

LIT: Right, right. And this is related to that question. Does the act of remembering help a writer make peace with the past?

HM: It always does for me. What usually happens is I go deep into memory. I write the poem or the book. And then I forget everything that’s in it. It’s sort of metabolized, made use of, or clarified. So it’s kind of a process of integration, I think at its best.

LIT: At the time when you decided to terminate, it seems like the decision was strictly personal, not political. Given what’s happened since 1969—the passing of Roe v. Wade in 1973 and its overturn in 2022, and the upcoming possibility of a historic election, do you see your decision in a different way now?

HM: Women’s relationships with their bodies have historically been private and personal. And made political and public use of. This is the first time in history women have been given the space to publicly tell their botched abortion stories. Think of it, on the floor of the Democratic Convention—which is 35,000 people and 70 million or more people watching TV—four women told their stories. That changes things. That changed the world.

If I were 23 right now, I might still be alone—there certainly are those stories of isolation. But there’s now plenty of information out there. And [having an abortion] is not generally considered so shameful. So a young woman has way more options as far as telling the truth is concerned. I wouldn’t say I think back on my decision as political, but the politics of women’s reproductive rights fifty years later are drastically different in terms of the power and size of the movement. Women’s reproductive rights are at the center of our politics now as never before and the voices in support of women’s choice are more consequential than they’ve ever been. It’s as if this thing over on the side—that the right turned into a political tool against women’s freedom—has moved to the center. Which is ironic, because now, because of Dobbs, the situation for pregnant women is so much more dangerous.

LIT: You wrote: “I think back over my unrealized loves, how each time it seemed to my imagination that he, or she, later again he, would solve it. Solve what? The problem of who I am.” Can another person—a great love, a spouse, a significant other—help us put a mirror up to ourselves and “see” ourselves for what we are? Or is that the stuff of romantic comedies?

HM: (laughs) A friend can help you see who you are. Of course, other people help us see who we are, but it’s not, typically speaking, the purpose of romance, the politics of romance. What you see in this book is a young woman who really believed the only way she could be a poet and playwright and writer was to have a boyfriend who was a poet and playwright and writer. I didn’t see it that way then, but I didn’t know how else to do it. So, often it’s that we want to be them. I don’t think that’s why men get together with women. They don’t want to be her.

LIT: You wrote: “I tell her that my best writing often begins in that anger.” Did you feel angry while writing this memoir, and if so, about what? How would you describe the dominant mood of A Termination?

HM: I’m still angry at the rock-bottom sexism of our society and culture. In writing this book, I wanted to investigate what had changed. One of the directions I gave myself was that I was just going to be very free in the writing. I wasn’t going to worry about what anybody thought. And so some days I was angry. And some days I was sad. Some days I was having fun. I think the book has a lot of different moods.

LIT: Why did you go with the parentheses style (e.g. on page 107 The Scarlet Letter, 1850) throughout A Termination?

HM: That’s because nobody knows anything about the past. I wanted people younger than me to read the book, and I wanted them to pay attention. I didn’t want them to just glaze over names and places they might not know about. So I put concrete dates in a book that’s sort of poetic. Doing that says, “these people are actually here. This is actually a thing that’s happening in real life.” And it’s also information. And also, they know what to Google, if they should happen to Google. And also, it was fun to do. I loved being able to say T.S. Eliot, The Wasteland, 1922 and the Beach Boys, 1967.

LIT: It actually reminded me of T.S. Eliot, The Wasteland, which was also annotated. It’s different, but…

HM: That’s interesting. I didn’t think about that. I just started doing it. And then I thought, I have to do this. And then when we were editing, we realized it had to be consistent. I mean, I did once have someone in my class [at the New School] who didn’t know who the Beatles were. But, then again, why should they?

LIT: Right.

HM: Of course, their parents probably weren’t born when the Beatles were, as John Lennon put it, more popular than God. So it’s like that—time passes.

LIT: What’s next for Honor Moore?

HM: I have a book tour I’m leaving for on Friday morning at 4 a.m. And I’m thinking about things, but I don’t know. I have no concrete ideas so far. Just little notes here and there. I never share things in the embryonic stage ‘cause it just ruins them.

LIT: All right, last question. Is there anything we forgot to ask that you would like to chat about?

HM: I want the readers of LIT Magazine to understand that the “sexual revolution” meant that people were having sex with each other all the time. In a way that people hadn’t before and don’t now. And that sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll was really actually true. I’m sort of amazed at how people don’t get that. And I also want people to understand how abortion was before. That a kiss could lead to the end of your life.

The following excerpt has been made available curtesy of the author and the publisher, A Public Space.

A TERMINATION (excerpt from: I Stand in the Middle of the Room)

There were two men who might have made me pregnant. I remember one night drinking in New York with friends, beginning a monologue that flowed as if it had been stored inside me like a long-lost, never-played recording. Are you all right? someone said. I was spinning out a fallback future: drunk, red-faced, obese, married with grown-up children. She dies in late middle age in an automobile accident, possibly suicide.

In a small house in Connecticut, a grand piano, a man playing Chopin. He always gets very drunk at his dinner parties. Jordan and Daisy, he says, addressing two of us on the cream-colored sofa (F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 1925). Which am I? Neither. Rereading in my fifties, I find myself not in the two women but in Nick Carraway, the narrator. I participate, make jokes, reply, but like him, I hold myself at a distance.

I climb the stairs of the outdoor lot and get into my Corvair. I had not told my parents I was pregnant. Such a fuckup, almost willfully skipping days of birth control pills.

My mother and abortion come into the same frame only when she is advised, pregnant for the sixth time, to have an abortion herself, that her health may otherwise be in danger. She refuses. Each birth was a canto in the epic of her childbearing, and I remember the story of that one: she felt the head sliding out, got herself to the hospital and almost instantly gave birth. My confirmation to the Episcopal

Church was the next day, and my mother was not there. I remember the weight of the bishop’s hands on my head, as she must always have remembered the solidity of my sister’s head emerging from between her legs.

I painted the white bookcase orange enamel and maybe the shelves black. I set its end against the wall so it extends into the room, a boundary between living room and dining room. My apartment in New Haven is the first place I lived in by myself. I placed my light-blue Royal typewriter at one end and will sit there to write. My favorite color then was blue, but orange was edging in.

I also had an orange suit, smooth wool and the light orange color of cantaloupe, with a long jacket I loved because it covered my shameful buttocks. What’s that behind you, my mother would say.

I want to stick to my subject, which is consciousness. When did I first smoke dope? Was I stoned when I invented my fallback future? When did we start talking about extending time, extending the duration of time. Consciousness and I think of looking at someone more intensely than usual.

If I’d had a son, would he have looked like one of my nephews? I think of him, turning slightly toward me. And into view comes a former student—it was as if he wanted me to be his lover. Can we have a cup of coffee? he said; I’d like to talk to you. Maybe that’s how I will come to have a son, in reincarnations. Usually, they are an age that would have them born close to 1969. Why didn’t you take him home? said my therapist more than once: a younger man I’d met in a café, the flirtatious waiter in the Indian restaurant two blocks from where I live. I wouldn’t do that, I said.

Diapers, and my mother trying to figure out a more efficient method—Pampers not yet in existence—dirty cloth diapers put in a drawstring bag to be picked up, a new batch delivered. Jab a safety pin first through one side of the diaper, then the other. Oh the softness of their skin: the smell of Desitin still makes me faint—it came in a tube like toothpaste; it signified clean, though the fragrance of baby excrement was not unpleasant.

The phone ringing, the doorbell ringing, a child shouting or weeping, the cleaning woman, the repairman, someone from the church. My mother spent her life distracted. A wave of noise slowing and fading out. I wanted quiet. When I managed to be alone, I was happy. An early quiet—one of the bathrooms in my grandmother’s enormous house, a very large tub with wide, silvery spouts, the soft sound of water rushing, then it’s full, the water aqua. You look out the window to green fields, the Guernsey cows with their rust-brown-and-white coats. I have a black-and-white snapshot of two of them in a field there, in a silver picture frame. In the distance, the dairy where milk and heavy cream were bottled, butter churned, cottage cheese cultured and strained.

I tell my grandmother about my apartment and ask her if she has an extra bed and she sends one, brass, from the governess’s bedroom. I ask her for a rug and she says, Go buy one you like and I’ll pay for it. I didn’t know where to go for a Persian rug like the ones she had, so I went to Greenwich Village and bought a Navajo one that was too small. I asked for a clock and she sent me some awful modern brass thing. It’s possible she didn’t know I was lonely for old and precious things.

One day in college, I decided to be happy. I woke up sad and looked in the mirror over the bureau and smiled at myself. Good morning. Good morning. I’d smile back at myself and then go to breakfast in the dorm. It was something I told friends about, a mirror trick.

Diet pills were my mother’s idea. She didn’t like what was happening to my body, breasts, bottom. Small orange pills and I’d have no appetite. My mother did not menstruate until the age of sixteen, was “flat chested” until she had children. It was she who wanted nine of us, eighty-one months of her body’s life. Big, small. Fat, thin. Would her body ever return to normal? A decade after her final child was born, she put herself on an early version of the Atkins diet—high protein, no carbohydrates. I have always associated rare hamburger with the cancer that killed her.

I keep the pills on top of the orange bookcase. I run out of them and my mood plummets. I did not want to be estranged from how I really felt, I thought, so I went off of them cold turkey and told no one. For days, I felt so heavy I could hardly get up from a chair, so far down, I thought I would die. It was about then that I lost the gold pin, textured and set with tiny sapphires and rubies, that my aunt, my godmother, had given me. I had worn it on the apricot suit with the long jacket.

Once, in my sixties, on a massage table I hallucinated myself within my mother. Her vagina had a narrow opening, its walls were dry and stiff, and I couldn’t get out. I believe that my skull was slightly distorted in shape at birth. You can see it still, the opening for my right eye slightly smaller than the left, the right side of my face slightly compressed. I think it contributed to the headaches.

It has always been that way, my father would say in a tender tone of voice. Your face has an asymmetry I like, said the older European woman photographer when I was in my forties.

It’s the summer I graduated from college. The large living room of a second-floor apartment on Mount Auburn Street. Empty coffee-stained paper cups and vodka bottles, stench of cigarette smoke. A classmate and I, both women, have arrived as arranged, expecting pages of the script, and he

is making excuses. Tomorrow, he declares. The season will open with his translation of Aristophanes’s Peace. The year is 1967 and the draft is on, now thirty-five thousand recruits per month.

Often we’d pull him from his bed: Okay, okay, okay. Not vodka, I now remember, but rum and “Coke.” He drank too much, but he was the engine of our theatrical endeavors, redeemed by talent, excoriating wit, charisma, his status as a brilliant young man. He got sentimental like any drunk, but I was still scared of him. I had ways of dealing with the fear: I folded it up and placed it on the shelf where I kept the perfectly adequate dimensions of my real self—she had no language, the fear was chartreuse, acid green.

He was my first gynophobe. He made unpleasant allusions to the female anatomy and coached actresses as if they were strippers. Give it all you got, baby. That’s it. Come to Daddy. He had unerring intuition, got what he needed in a performance by verbal assault, insult, flattery, and seduction.

I enabled him. All the women did, I want to say; now I see that we were two kinds of women. Those of us who were at Radcliffe or in for the summer from Vassar. And girlfriends or one-night stands recruited in Boston bars, he seduced into costume design, bed, or both. Such a snob. I had nothing but contempt for those women.

I am Margaret Fuller and I accept the universe. Words of a play I saw in the early 1970s (Megan Terry, Calm Down Mother,) the first ever I saw by a woman of my generation. The actress had red hair. I have never forgotten her, a large awkward woman with coppery hair alone on the stage: I am Margaret Fuller and I accept the universe.

“A Termination” was published on August 27, 2024 by A Public Space.

Honor Moore’s previous six books include a biography, two memoirs, and three collections of poems. The Bishop’s Daughter was shortlisted for the National Book Critics CircleAward and was an LA Times Favorite Book of the Year. "Our Revolution" was featured on the New York Times Paperback Row. She has edited six anthologies, including "Poems from the Women’s Movement" and, with Alix Kates Shulman, also for the Library of America, "Women’s Liberation: Feminist Writings that Inspired a Revolution and Still Can!" Among her awards are fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation in nonfiction and the National Endowment of the Arts in poetry. She lives in New York City and teaches in the MFA program at the New School.

photo by Spencer Ostrander