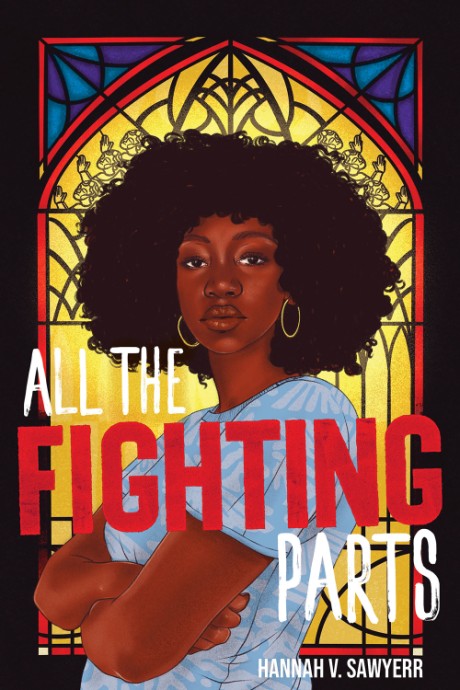

“All The Fighting Parts” an interview with Hannah V. Sawyerr (poetry ’22) and an excerpt from her debut YA novel

Interview by Jonathan Kesh

All The Fighting Parts, the debut novel in verse from Hannah V. Sawyerr, is a challenging, poetic tale about overcoming trauma and learning to fight back.

The story follows high-schooler Amina Conteh as she struggles to navigate a tightly-knit community centered entirely around the charismatic Pastor Johnson, who runs the Holy Tabernacle church. When the pastor attacks Amina one night at the church, she finds herself isolated, no longer sure of how to use her voice and unable to connect with her loved ones within Pastor Johnson’s orbit.

All the Fighting Parts is very much a story about healing, as Amina chronicles the challenge of rebuilding her life through poems and journal entries. Personal relationships are complex: not everyone wants to take sides, although many do for good or for ill, and even Amina’s supporters frequently attempt to control how she tells her own story. While we’re mostly in Amina’s POV, the novel often weaves in text messages, internet comments, and police transcripts, showing both the power of community to rally around a cause and the way it can make spectacles out of tragedy.

Hannah V. Sawyerr’s young adult verse novel comes out in September from Amulet Books, and she spoke to LIT about voice, verse, and power within religious communities.

LIT: All the Fighting Parts is written in verse, it’s told mostly through poems, interspersed with police interviews and journal entries and text conversations from the narrator, Amina. Did you feel like writing in verse allowed you to tell this particular story in ways that you couldn’t convey through prose?

HANNAH V. SAWYERR: Yeah, most definitely. I definitely felt like I needed to tell the story in verse, and I was sure that I needed to tell the story in verse, because I originally tried to write it in prose and it just was not working. I think when you write in verse, it allows you to stay in the head of the protagonist. A lot of particularly emotional novels are told through verse, and I also think that I needed to incorporate the mixed media because I needed to show other people’s perspectives while still centering Amina’s voice.

Even though we stay in Amina’s head for the majority of the narrative, being able to incorporate news articles and court transcripts of other characters was a way for me to show those perspectives while also still staying very, very close to Amina and amplifying her voice.

LIT: That ties a little bit into what I was going to ask next, because I was wondering if you could talk about how this book came to be. Did the book change at all while you were putting it together, or is this final version the vision you had from the very beginning?

HS: The book changed in subtle ways, but I was very fortunate to have an editor who really prioritized the story that I wanted to tell. And so if anything, my editor kind of pushed me to dig a little bit deeper, just to make the story a bit more compelling. She encouraged me to ask myself the hard questions, like “how can I raise the emotional stakes in a way that is engaging but still honest?”

But for the most part, I think the story really stayed the same. If anything, the order of events changed a little bit. I know I spoke a little bit about the court transcripts from other people’s perspectives. In earlier drafts, those transcripts were only from Amina’s perspective. My editor challenged me to include other perspectives to show just how her community is handling this event that affects both Amina and the people around. If anything, I was just challenged to make the story a little bit more compelling by thinking about the difficult things. But the story itself didn’t change much.

LIT: Getting into the actual story here, much of this story follows Amina as we first see how she’s part of this bigger community, and then how she becomes isolated from all of it after the assault occurs. Amina herself is struggling to piece together what she needs to move forward. What is Amina chasing over the course of the story? What does she need?

HS: I was actually thinking about this not too long ago. I don’t think Amina knows what she needs. And I think that is because Amina struggles to believe that she’s worthy of community, and worthy of support, and she kind of rejects that for a long time. But at the same time, it’s something that she deeply craves. She craves to have a better relationship with her dad, she wants people to understand her but she doesn’t believe that she’s worthy of that.

Amina needs to confront the issues that she has with herself and how the assault has affected her. But I also think Amina needs and learns that she doesn’t have to do that alone.

LIT: Religion is presented as a very complicated force here. The assault that’s central to the story is committed by a pastor at Holy Tabernacle, which is the cornerstone of Amina’s community. Most of the characters, especially her loved ones, have some sort of connection to it. Amina herself is unsure where she stands with her religious beliefs. What role does religion play in the story?

HS: I’ll say this about religious communities specifically because that’s what this book is about, but I think this applies to lots of communities. I think in a lot of religious spaces, especially when they’re led by people who are well-liked or popular community figures, people turn their backs when the people who are in positions of power do these things. And I think that’s what allows those cycles to continue. Unfortunately, I think the church has a track record of being a place that people find refuge in, but it’s also a place where a lot of people have taken advantage of their power, and it affects young and vulnerable people like Amina. Although I don’t think this just affects young people.

Amina grapples with the fact that she does see the church as being a place of refuge for her father. And she does see how Pastor Johnson helps a lot of people out in the community financially, and by being a face of hope for people. But she knows him as someone that has caused harm to her. So she grapples with knowing that if she speaks out against this person, it’s going to affect the people he has positively affected. But if she doesn’t speak out, it’s only going to cause her more harm. And so she grapples with that for a lot of the novel before speaking out.

LIT: There are several authority figures, such as her father, her teacher, the police detective, who have good intentions but a very rocky relationship with Amina. She often feels like they’re causing trouble when they may not mean to, even when they believe they’re helping. What creates that sort of tension between these characters and Amina?

HS: A lot of the adults in Amina’s life mean well, even when it’s hard for her to feel that way. I’ll talk specifically about her father because he’s one of the most nuanced characters in the entire book. Her father has always had good intentions, but he has caused her a lot of harm. And that’s reflective of real life relationships. A lot of the time, we mean well but our actions cause a lot of harm. I’m thinking of one particular scene, and without really getting into it, her father has really does think he is protecting Amina from Pastor Johnson what he’s really doing is taking away her chance to speak. And that’s something that is incredibly important to her. And it really affects her deeply.

LIT: During the book, it comes up a few times that Amina feels like she doesn’t have control over how her story is being told, that all these outside forces are trying to retell her story while Amina herself struggles with how she wants her story told. Is that what you were going for?

HS: Because Pastor Johnson is a popular figure, Amina’s story is something that the people in the community talk about. It does make local news stations. And when things get to that point, a lot of times it does feel like the narrative is no longer yours. The narrative is whoever the journalist is, the narrative is whoever is talking about your story over breakfast. So she does feel, and rightfully feel, that the narrative is being spun in a way that doesn’t favor her. A part of Amina’s fight is reclaiming that narrative.

That was true for me as well. When I came forward, at the time, my church community was the largest and closest community I had. I felt like my story was made available for people’s consumption, and that was hard. I think that is one of the ways that Amina and I are most similar.

LIT: What does it take to regain that kind of control over your own story? In Amina’s case, it feels like toward the end, she’s starting to.

HS: I can speak for myself and for Amina when I say I think it really starts with accepting the community that you deserve. I also think it’s worth saying that it’s difficult, but I also really needed to learn that slow moving progress is still progress. I had to learn how to be patient with myself.

LIT: Amina’s hobbies, journaling and jigsaw puzzles, come up a lot as an outlet for her throughout the story. Is there a significance to those two activities in particular?

HS: The jigsaw puzzle was completely random [laughs]. I’m not gonna lie. Amina’s known for being vocal and a bit combative but she’s incredibly smart. And she always has so much on her mind. I was like “what would a teenager like her be secretly into?” And I thought “jigsaw puzzles!” And it kind of just stuck, it was actually something I considered going back and changing but I felt like it makes sense. Especially because she’s navigating all of these changing parts of her life and just trying to figure things out.

My reason for her being into journaling was a bit more straightforward. Amina has so many complicated feelings, and I felt like the journal was a good way to straighten those feelings out. It’s also a way for her to connect with her mother who has passed. Her mother used to journal. So while she may not love school, or in the beginning, only uses her journal in church. I think she starts to journal more, one, to process what’s been happening with her, but also to have that deeper connection with her mom.

LIT: What were some influences while you were working on All the Fighting Parts?

HS: The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo was one of the first verse novels I’d ever read. The book I read as a kid that was closest to a novel in verse was probably The House on Mango Street, so The Poet X kind of helped me believe that these stories could be possible. The same with Blood Water Paint by Joy McCullough, also the book Grown by Tiffany D. Jackson, which was also another one of the comp titles for All the Fighting Parts. It’s also a Me Too novel, centering a black girl. Those are the books that made me think a book like mine could be possible, and that it could also be important.

LIT: What are you hoping readers will take away from this book? Are you hoping it could be a resource for people who need it?

HS: First and foremost, I want people who have been through similar situations to feel seen by the book. I always say that for me, writing All the Fighting Parts was me protecting my younger self in a way I wish a lot of folks did. I also want it to start conversations, that’s very important to me. Because I do think that when these situations happen in communities like Amina’s, that they’re not handled the way that they should be. A lot of the times, people tend to support the abuser, and I want us to consider why it is people do that. I want us to consider the effects of not believing survivors, especially when their abuser is someone who is as powerful as Pastor Johnson.

This excerpt is curtesy of Abrams/Amulet books, All the Fighting Parts publishes on September 19, 2023.

SAME OLD SUNDAY MORNINGS

No matter how many colds I fake,

in my home, Sunday mornings are always the same.

Unless you have a 102-degree fever,

or are puking through your nose uncontrollably,

from 9:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. your ass is in a church pew.

I’m not sure if I’ve ever truly liked church,

but for my father,

the church is a place of refuge.

A safe place to rest in.

And if you’ve attended as many services as I have,

the church finds a way to become a part of you.

You hate the man who always tells you

You’ve grown so much!

but can never remember how to pronounce your name.

You hate the woman who says your dress is

Soooooooo cute!

and would be

Sooooooooooooo much cuter!

if it could be just

a little longer

or

a little looser.

You hate all these things,

but love the old woman

who has been there your entire life—

and most of her own too—

who smiles at you

from the same (unofficially) assigned church pew

occasionally offering you bottom-of-the-purse candy

(the best kind of candy).

You fall in love with the drums accompanying the organ

while that one woman shouts “Glory!” at the top of her lungs,

starting what I like to call

a

holy

ghost

domino

effect,

also known as a church-wide “praise break.”

It becomes worth it when I see

my father—a man whose face

remains soldier stone straight—smile

whenever Pastor Johnson shares an encouraging word.

It becomes worth it on the days

when I can remember my mother only in

fragments.

I remember,

this is a place that made her feel whole.

Hannah V. Sawyerr was recognized as the Youth Poet Laureate of Baltimore in 2016. Her spoken word has been featured on the BBC’s World Have Your Say program, as well as the National Education Association’s “Do You Hear Us?” campaign. Her written word has been included in Essence, gal-dem, and xoNecole. She holds a BA in English from Morgan State University and an MFA in Creative Writing from The New School. Sawyerr is an English professor at Loyola Marymount University and lives in Los Angeles, California. ALL THE FIGHTING PARTS is her debut novel.