Collecting 92 Years of Wisdom by Chelsey Clammer

Collecting Ninety-Two Years of Wisdom

“The silver Swan, who living had no Note, when Death approached,

unlocked her silent throat.” –Orlando Gibbons

It’s some night we’re fighting—or, maybe it’s after a bite-sized disagreement (just a morsel of our routine arguments, just a crumb of our crumbling marriage)—when Husband asks, “Do you hate me because you think I’m like your father?”

Odd to be having a conversation with my husband based on the assumption that I hate him.

I explain: It isn’t that I hated my father, at least not now, not in hindsight, not after his death. What I hated was that he was sick and didn’t stick with his attempts to change that conditional fact—even after rehab and a halfway house and another relapse. Maybe this is about my impatience with him and now my husband. About fear and the cycles of an unattended to mental illness. How Husband won’t take medication for the illness whose paranoia symptoms start many of our strained fights. This is definitely about repetition. Cyclical stand-offs.

And yet I convince myself that each one of my husband’s absurd accusations and rages are localized events. That they won’t ever happen again, even though I know they will. But sticking with it, seeing him through each episode—like how my mother stuck with my father until the end—is what this is all about.

Marriage.

***

You’ve seen it. Two swans posing: heads bent down, forehead-to-forehead, bill-to-bill, the contact that makes their necks curve, arch out, then dive in. The graceful heart image they make together.

The heart. It is not a quiet expression, not faint. For swans, once a mate is found, the relationship is considered long-term. Swans are monogamous, are in it for life. In this.

We’ve created a type of reflection for longevity’s power through these birds. We look at them in aspiration, for inspiration in how to create the kind of bond that lasts.

On every wedding anniversary my grandparents had, my grandma would state how many years they had been married. Then when I congratulated her on however many decades, my grandma would say, “No. It’s embarrassing. It means I’ve been with the same man for over 60 years.”

I understand how she projects embarrassment when I suspect there is an actual sense of pride living within her because there is something to be said about devotion. About the beauty of not giving up. All of this gives me hope, assures me that I can spend a lifetime with a loved one.

Swans are birds of habit. We humans habitually impose meaning onto things. We need the swans to mean something to us, to latch our desire for love and tranquility onto the sight of two swans bowing, to believe that we, too, can create that powerful image of love. The heart.

Right now, I just need someone to show me how to do it.

***

“Sorry I just have to vent.” Mom has been saying this over the phone to me a lot lately. Me too. She vents about grandma. I vent about my marriage.

“Have at it,” I say, my ears fully prepared.

I’ve been preparing for my grandmother’s death for the past seven years or so. The phrases, “this might be her last Christmas” and “there’s no way she’s going to make it through another winter” have projected from our lips for almost a decade.

Grandma has been a common source of family conversation lately. The effects of her declining health incite forever-circling phone calls with my mother. The effects: bitchy, depressed, obstinate, needy, demanding, bits of dementia that spur frustration for all parties involved, and how much you have to shout over that damn TV for her to hear you.

Though, when not possibly dying, my grandma is the sweetest. Kind, patient, always offering food and a hug. I’ve forever felt safe and well-held in my grandma’s presence. My grandma whose lap I would fall asleep in as a child, and my grandma who, when I was 19 and visiting her and sobbing one night because my first girlfriend broke my heart, said, “I don’t understand the whole lesbian thing, but I love you anyway.”

That sort of sweet grandma who means everything to me.

But now that she’s dying and getting a tad bit bitchy about it, my mother and aunt are going insane because they have been attending to their 92-year-old, stubborn mother and they need a break.

I need a break from my marriage.

An idea forms.

I’ve been wanting to visit my grandma again before she dies. Plus, my husband believes she is a source of wisdom and that her 60-plus years of marriage experience could help guide our own marriage back to the land of loving and healthy.

Mom insists she’ll just drive me crazy. She might not be wrong about this.

Regardless, I’m excited to go, to help take care of my grandma.

What I mean is that I don’t want my grandma to die without me getting to know her, to hear her stories of marriage I’ve never known and need right now.

***

The nest is a sacred space for swans. It’s where life is hoped for, and it’s where that hope comes to life. Together, a young couple builds their first and only nest. Only? Yes. Because after initial construction, swan home upkeep is an act of annual nest restoration. Each year, swans leave then re-arrive after that long migratory return flight home, back to the nest they built, soaring up to one thousand miles at 50 mph the whole way with their heads and necks extended gracefully. They need no road signs or maps or GPS. Swans instinctively know their way back, how to navigate the one thousand miles to return to their nest.

Grandma’s home is a place of knowing. A place of, well, home.

Two homes, actually. Back in the ’70s, after my grandpa retired from the FBI, my grandparents built a house in Cripple Creek, a small mountain town. Then, a few years later, they moved to Colorado Springs to be closer to civilization, but kept the house in Cripple Creek.

Each year, I take at least one road trip to go on a vacation in the mountain house. My friends and I will drive from Austin to Cripple Creek—a 14-hour migration north—to have some fun during spring break. We always stop first in Colorado Springs to say hi to my grandparents and get the mountain house key.

That first year we did it, we arrived in Colorado Springs at 6 a.m.—two hours before we told my grandparents we’d be there, two hours before I could call them to get directions to their house from the highway because I’d never driven there myself. What to do for two hours? We couldn’t call them—without hearing aids my grandparents would be too asleep to hear the phone ring.

So I just drove to their house by instinct.

Not one wrong turn.

Her home a nest I instinctively know my way back to.

***

There, in Colorado Springs, in the house where my family has gathered for decades, our lives collecting holiday pictures year after year, with the green porch swing suspended out front, the guest shower still spraying hot water at a deep-tissue massage pressure, where I swear that bar of soap has been there for decades—that’s where I go. That’s where I’m staying.

The house is familiar to me like Grandma’s voice and accent, like her insistent instructions to, “Just make ya-self at home.”

My grandma grew up in Oklahoma where any words resembling those that end with “er” turns into a sort of “uh.” Wuhds such as wa-tuh. Also, Houston is You-stun. And wash is worsh, of course. And when I visit her this time to get a little marital time-out as my husband and I let the lava of our explosive arguments settle, she’ll say one morning that her car needs some gas so, “we’ll have ta go to the fillin’ station today.” She still shuffles around her house like she always has, though now oxygen tubes follow her trail, at times wrapping herself around the kitchen table, “Like a dog teth-uhd to a tree,” Grandma says.

We will laugh at past memories.

Like how when my dad died and our extended family flew in from Colorado, filling our house with sympathy and sorrow and then, the day before the funeral, my grandma’s front tooth fell out.

“I look like a damn witch,” she cackled, bringing some laughter to a somber situation.

The difference of 60 years’ worth of stories will fill the space between us. She will sit in the blue recliner she has been sitting in for over 33 years, with the pink pillow resting between her neck and the chair. She will tell me stories as I sit next to her on the fluffy brown carpeted floor. I have 33 years’ worth of memories sitting on that floor. Holidays. Vacations. Family visits. Opening Christmas presents. But that first night with my grandmother will be a story I’ve never lived before as I will hear her unknown-to-me narratives.

We will fill the crisp, November night air with unexpected, untamed laughter and narrative. Like this:

“I started college at Tulsa University,” Grandma begins.

“I didn’t know you went to college.” Total surprise to me. Already, stories of this woman I’ve known for all my life have begun to blossom.

“Oh yeah. I went for a few years to become a typist. Well then my sophomore year, I transferred to University of Arkansas.”

“How come?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Grandma’s signature phrase for when she’s about to enter into an explanation. “I liked their football team,” she says with a laugh, slapping her knee like she always does when she knows she’s saying something funny. “Now at University of Arkansas, I was in a sorority.”

Another surprise to me.

“And one night, one of my sorority sisters invited me to a youth event at the Presbyterian church. I said, ‘Phff, I don’t know. That’s just not really my thing.’ But then she told me there would be free food and guys there. So, I said, ‘Well alright. Let’s go.’ And that dinner was real good.

She pauses as I smile at how much I love my grandma even more after learning this fact.

“I don’t know why I’m telling you all of this.”

“Because I want to know,” I say, not including the second half of that statement: before you’re too dead to tell me.

“I guess I’m just a lonely old woman with too many stories to tell.”

She continues, keeps telling me the trajectory of how my grandparents came to be. “Now there were, oh I don’t know, a dozen or so guys at that church event. They all came up to me and we talked for a little bit. I remember a few of them were real good-looking. Well, about two weeks later, the phone rings and one of my sorority sisters said it was for me.”

Here, her eyes stare a little bit further into space as if she’s seeing that moment again, re-living the event that would lead her to her marriage.

“I said, ‘Hello?’ And your grandfather says, ‘Hi Betty Ann. This is Bob Hall. We met at the church a few weeks ago.’ Now, Chels,” my grandma cuts in on her own story. “For the life of me, I couldn’t remember which one he was. I had no clue. I said yes when he invited me to go to a movie, even though I had no idea who this man was.”

She lets out a little laugh as she remembers that moment, remembers a few days later when she was waiting for this guy named Bob to come and pick her up and she still couldn’t remember what he even looked like.

“Well, when I met him I thought, ‘Well, he’s not all that bad looking. I could have done worse!’” Another cackle, another leg-slap, another memory of destiny recounted. “I don’t remember what movie it was because the whole time I just kept thinking, ‘This is such a great guy.’ Well then a few days after the movies he called again, ‘Betty Ann? This is Bob Hall.’ I said, ‘Oh hi there, Bob!’ And then he asked me if I wanted to go steady with him and I said, ‘Well isn’t that what high schoolers do?’ Either way, I said yes and I just hoped that he could dance good. He couldn’t. But I married him anyway!”

October 26, 1946, The Hall family from which I will come begins.

If my grandfather hadn’t died five years ago, their seventieth anniversary would have been this year.

But he did die, so that didn’t happen, and then Grandma was forced to do something she had never done before—live alone.

***

When a female swan is missing her mate, she restricts herself. That is, she eats less when separated. How to keep the body going when the heart no longer feels like pumping? Broken. Numb. Stolen. Life skills suspended until her significant other returns.

Without grandpa, who is there to hear grandma? To keep her heart excited and pumping? To keep living? How to share your life when you’re alone?

And why does being away from Husband right now feel this good?

***

Here I am, keeping Grandma company, driving her to doctors’ appointments and the fillin’ station, helping her open her mail, explaining her bills, and balancing her checkbook. Her eyesight is full of shifting spots that fog up and blur the buttons on her microwave. Three days into my stay, Grandma manages to zap a cup of tea for so long (ten minutes instead of one) that it boils, explodes in her microwave, the turning tray then swamped in herbs and leaves, looking like her yard did before I raked it yesterday. As I raked, Grandma kept watch from her living room window, coming outside at one point to give me a glass of water, even though I wasn’t sweating because it’s November in Colorado. I told her thank you anyway, got back to the leaves. A collection of moments later, after I had gathered another three bags of leaves, I looked to the porch and saw the glass of water, refilled. How she must have been watching, worried about my ability to do this alone. So, she did what she could, got me water. Refilled my glass. Grandmothers are like that.

And, while I’m here in Colorado with space to think and breathe, I realize that marriage is like this: tea and the explosive effects of mindless mistakes that can instigate a strife. How not attending to any issue creates more tension, letting things broil, not stopping them before they rupture, which is when the connection boils over into arguments and soon elements of your marriage are burnt, fractured bits sizzling.

Maybe, then, marriage is an act of keeping the flame low, of letting life steadily simmer. Two sets of eyes and two sets of knowledge and experience watching for errors, for preventing things from reaching the point of you-can’t-take-that-back.

Because what’s not attended to sizzles, erupts.

Marriage, now metaphored.

***

While at my grandma’s house, I take a few silence breaks––that TV is extremely loud. When grandma’s napping or occupied with whatever activity can occupy an almost deaf, almost blind 92-year-old woman, I clamber downstairs to the basement to squeeze in some writing time.

I’m trying to write about a moment with my father because it seems significant. It’s a memory from over a decade ago, a few years before he died, when he was out from rehab and coming home. We hadn’t spoken for 28 days, and I was still angry because I was 19 and broken-hearted and needed to funnel my anger on someone, so I chose my alcoholic father. He was just then out of rehab, coming home, and I didn’t know that he was on his way home and he didn’t know that I was home—a confrontation just waiting to happen between two people whose relationship strategy with one another was avoidance.

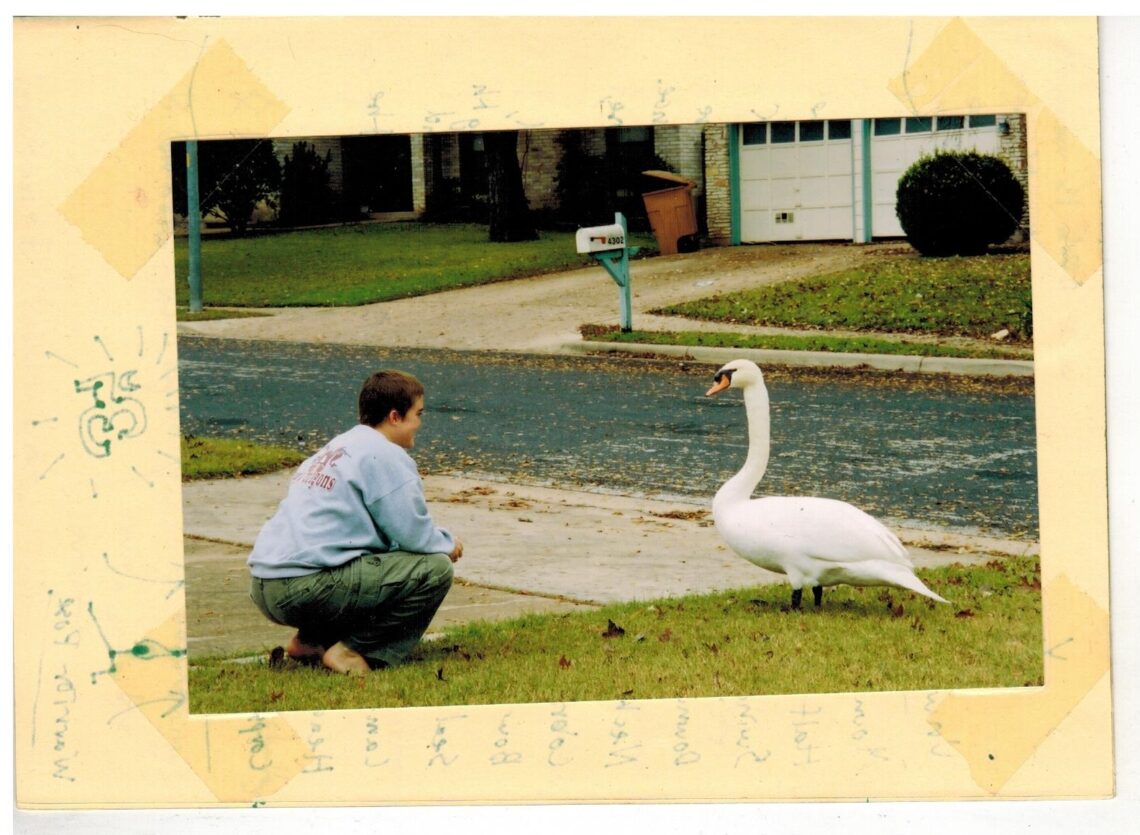

And then a swan enters the picture.

He sees that I’m home when he pulls up to the house to find me squatting in the front yard, a huge swan in front of me that I had seen moments before while sitting in the kitchen, its presence pulling me out here.

A swan. In Texas. Where they don’t live. Where they don’t ever go. In a residential area with few water resources around. This is extremely odd, this swan.

My mom and I saw the swan moments before my dad pulled up. When he saw me and the swan, my eyes shifted from swan to him, and the 28 days of silence and all that misplaced, brewing anger dissipated. We smiled at each other, then back at the unlikely swan.

I’m trying to find meaning in that moment while I’m writing at my grandma’s house. I turn to swan facts in search of symbolism. But as I read more about swans, what I discover is not some closure with my dead father via creative writing, but a reflection of my current situation—marriage, what all it means, how to practice it, and how older generations can guide the youth through love and life. Yes, the swans are no longer about my father.

***

There is something to say about swans. About commitment and wisdom and trust-your-elders intuition. Metaphor coming to fruition. Here. Make analogy speak—glisten. Listen.

Most swans are named for the sounds they make. Trumpet. Whooping. One swan is named for the sound it does not make. Mute.

Husband and I agreed not to talk as I stayed with my grandma, collecting her 92 years of wisdom. We thought the silence could do us some good—to stop whooping and trumpeting our arguments and stubbornness, and to just take a break and go mute for a while.

I think back to our wedding. During the reception, we had everyone in attendance—a whopping 15 people—write down their marriage advice so Husband and I could read them out loud. This was one year after my grandfather died, so I never got to hear his advice. But my grandma wrote, “Bob & I always said that our marriage was a success because we have two TVs—Bob can watch his ball games & I can watch movies!”

Two TVs to give the married couple a break from one another.

During this state of muteness, this space of a break, I feel relieved. Unburdened. Like I’m finding my way back to me—my story—as an independent woman, inspired by the kickass woman who came two generations before her.

All of this during such needed silence from an exhausting, floundering marriage.

***

What is it to just sit and listen to other generations tell their stories? To have life narrated by those who have lived it the most?

I look into her big blue orbs—eyes brimming with recollections and treasured memories.

My grandma tells me the story about how grandpa brought an ex-convict home for dinner once. As an FBI agent, he specialized in bank robberies, and when one of the men he had put in prison was released on a cold night and had a long train ride ahead of him, Grandpa called Grandma and asked her to make another place setting for dinner. He didn’t say for who, just someone from work.

“I guess he felt sorry for the guy,” my Grandma comments. “He just wanted for the guy to have a good meal and to be around a family.”

Here’s where silence and trust co-mingle, how my grandpa wouldn’t say who, and how my grandma didn’t ask, trusting that her husband had a good reason.

“Now I don’t know what this man did to get himself in jail, but he was a really nice guy and said, ‘Yes ma’am’ to everything. Real polite.”

After the man left, my grandma asked my grandpa who that man was.

“‘Oh, Betty,’ your grandpa told me. ‘Don’t worry about that. He served his time. He’s a good man.’”

Here is the silence of trust, where yes, marriage is about the give-and-take and yet how sometimes you don’t do either but just stay quiet, let it be, let love circle around itself and lie down in the moments when things are better left unsaid—where silence might incite suspicion, but nothing negative grows.

I’m hoping this separation is a silence that will start to re-grow trust in my marriage, even though I’m doubtful.

Grandma says marriage is about the give and take. The concept of balance now comes to me. Night and dark. Yin and yang. Silence and such unbearable cacophony.

“It takes two to tango,” Grandma says.

***

These bits of stories aren’t the marriage advice I had hoped for, but similar to how I set out to write an essay about swans and my father, and how the essay has shifted to being about my grandma, the intention of what I hoped to learn has also shifted. I can sense my marriage might not have much breath left in it and I don’t think my grandma can take any part in reviving it. So here I am, getting to know my grandmother (who probably doesn’t have much breath left in her, either), to hear her stories of love lived, letting me know that things might not always turn out how we expected or hoped for. Husbands may be terrible dancers, college enrollment changes because of an affinity for a football team, church dinners might turn out to be real good—and that’s life. And if we just roll with it, the unexpected becomes our treasured life stories.

And maybe, just maybe, by the time we get to the end of our lives, we’ll find someone we can retell our experiences to. Let the stories—our voices––be heard one final time.

***

The swan song is the one last blast of beauty that’s released right at the moment of a swan’s death.

More than just a collection of noise, it’s a long mournful sound, a “bugling call.” A drawn-out series of running notes that soar and traverse up an octave, more than just how air escapes up the tracheal loop that stretches along a swan’s sternum, that final exhale is more than just a side effect of lungs collapsing. More than just a melody extending until there is no air left to sing, the swan song is seen as a final performance. An ending accomplishment.

***

At home, he mocks me. Again. After I’ve said more than once there will be no mocking of me because that is immature.

I have called him immature. Again. More than a few times. After he has said more than a few times that I am not to use the word “immature” in reference to him because of its judgmental overtones.

It has been five weeks since I left him, four weeks since I returned from Colorado and nothing has changed and so I moved out for real and have been crashing on my sister’s couch. We have started the real separation, have put it into motion. But he won’t detach from his maltreatment of me.

He mocks me. Again. On the phone this time.

A heightened moment in a screaming match: “Wha-what are you gonna do?” he asks in a taunting tone, “Leave me? OOOOHHHHH.”

“Say that again!” Screaming, I put him on speaker phone, wanting my sister who is sitting next to me to hear him. I know he won’t say it again, so in the second of silence I have to speak my mind, that second in which I can realize this isn’t love that lasts, I start screaming what it is I need—that final word, this marriage’s grand finale:

“Divorce! Divorce! Divorce! Divorce! Divorce!”

Husband hangs up.

This conversation—this marriage—is over.

***

Highly intelligent beings, swans are able to remember who has been kind to them. Who hasn’t. Those who have, receive their loyalty. There’s something to be said here about longevity. A type of foreverness in swan relationships. You can see it in that silent gaze, in their eyes that look longingly, lovingly at the mate they are certain will be the only being in the world they will love. A pair of swans live out their lives together. They migrate to and fro, making eggs-turned-cygnets an annual event. Swans are monogamous, which is why, I imagine, it can take swans two to four years to find their ever-lasting mate. Such a life-altering decision to make.

Husband and I dated for six months before we married.

***

Twenty-three days before my divorce is finalized, my grandma dies.

***

The vocals of mute swans may be nothing more than a feather-soft whisper—an incited hiss, an occasional honk—but with the accumulation of different myths, stories, facts, and centuries-long observations, the mute swan gains voice in its final act.

“She poured out her words of grief, tearfully, in faint tones, in harmony with sadness, just as the swan sings once, in dying, its own funeral song.” –Ovid

I had hoped that my visit with my grandma wasn’t our relationship’s swan song, our last show of connection. Affection. That our practice of love and listening and learning was not a final performance, even though I knew it probably would be.

There is something to be said here about needing a soothing sound in someone’s final moments. Because the swan song is for the listener, not the singer. Whether fact or fable, we abide by and practice that need to hear the inception of our oncoming, long-lasting grief.

Memories—and moments—that will echo.

Chelsey Clammer is the award-winning author of the essay collections Human Heartbeat Detected (Red Hen Press, 2022), Circadian (Red Hen Press, 2017), and BodyHome (Hopewell Publications, 2015). Her work has appeared in Salon, The Rumpus, Brevity, and McSweeney’s, among many others. She teaches online writing classes with WOW! Women On Writing and is a freelance editor. www.chelseyclammer.com

Chelsey Clammer is the award-winning author of the essay collections Human Heartbeat Detected (Red Hen Press, 2022), Circadian (Red Hen Press, 2017), and BodyHome (Hopewell Publications, 2015). Her work has appeared in Salon, The Rumpus, Brevity, and McSweeney’s, among many others. She teaches online writing classes with WOW! Women On Writing and is a freelance editor. www.chelseyclammer.com