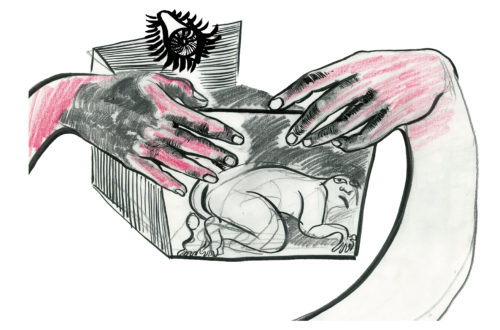

“Diana the Thoroughbred” with Artwork by Rebecca Pyle

Above: “The Carousel and the Racehorse”

Pen, ink, and watercolor.

They were headed for the track, one of the ones the Queen liked to enter her horses in. Gavin in his college days with friends had once gone to a track, but he had sworn then he would never bother again: it seemed a habit like smoking, sure to leave you wishing you had never begun, or like the habit of continually trying to meet girls, which would backfire, leave you apologizing or making excuses to half of them, not a spot you should want to find yourself in if you valued simplicity. Or sanity.

He was finding out today, this special day, what it was like to be in insulated and socially insulting Daimlers and Range Rovers, cars that took the offensive at every corner, every glimpse. Wealthier than you, they sang. Predisposed to having offended someone: he’d heard the royal family’s were bulletproof.

Now in one with his invisible friend who was very like Tinkerbelle: he thought of Peter Pan, Captain Hook. What weapons had Hook had? Bullets? Or was it just cannons then? Pan would say Hook had every weapon, to have the thrill of more danger. Gavin was lost in Peter Pan memories just as the doorman sealed him into a dark glossy Daimler, the doorman shutting the door but Gavin trying to help by dragging its door-handle toward himself, dragging its heaviness like a Canadian sleeping bag. What a thick door, Gavin thought.

Thick as a plank, he suddenly remembered. His Tinkerbelle’s (Princess Diana’s) reason for not having gone to anything but…cooking school. I’m thick as a plank, she’d said. But that, Gavin had always known, was to throw them off.

Thick the gangplank they’d made her walk, or she’ had made herself, walk, with her thin lovely legs that looked like a thoroughbred’s horse at rest only for a moment, ready to go long distance. Gavin worried about the dead. He was, if you had to describe it in some way, a concierge for the dead. He helped them with their comebacks. But it was totally virtuous. He was a volunteer.

And he could admit this talent to no one. But it was expected. He was the son of a novelist.

He’d been in conversation, ghostly sort, with Princess Diana all day. Consider someone with polio, Diana was telling him—through the air—he could not see her. Just as someone with polio would not want to go with stablefriends to the stable, I did not want to ride a horse. Grew up with my sisters with their helmet hair and their little just so gloves, saw their little seats going up and down in the saddle just when they were supposed to go up and down. Saw the men sliding the reins all around and yes Charles with his dandery attitude and his sweaty polo arms and had the rides around town with him after the horse-crude events and oh how he liked to stare out a window and remember his great spins and turns. Just in time. Had this person seen that move coming? Surely that one? And weren’t they to be at that dinner the next week, he would have to ask his appointment secretary? And would I be wearing a new dress for everyone? Making me feel like the appointment secretary’s secretary because he always figured everything with the appointment secretary first and then I was informed I ought be ready like the dog’s dinner. The blouses that tied in a bow—they make me sick, remembering, now I have nothing to do with bows or beaus. My legs are strong, strong.

And aware of the envy too. The way you could ride across the ground and the horse took you there and yet so humbly pretended it did not matter that you asked them to do all that, asking nothing in return. I understand that now. If I’d ridden more I could have understood more. But I would have had to ride with the Queen. The taxi of taxis, really. I always was afraid, Gavin, she said, in a voice so pure and clear and humorous he looked around, thinking he would see. Her. Afraid so heavily, charging here and there like a derelict with a legal brief, she said.

He nodded, so wherever she was she might see he was in agreement. All she was now was a scent, pale blue, very Tinkerbelle. His clients—they all appeared for him, then disappeared before shape-shifting to what they wished they’d always been. He must show he was on her side. They were pulling up to the horse-racing place, a place new to him. She wanted him here as witness. A spirit needed a knower, a witness.

Where are you, he thought. To see if they were still in telecommute. But she made no answer. He found himself smiling. She was somewhere. Here. Where are you brought them in.

In this car, if it was possible, with its heavy polished leather scent, he still smelled the color pale blue. The Tinkerbelle’s pale blue.

Now they were sprung from the car, he and his ghost of Diana who had come with him, and he soon had a seat in the stands, very far up in the stands.

Far beneath him in his same section he could see the Queen with her great turtleishness—so many layers of fabric stretched smooth across her rounded back, ornamented at various edges with forbidding, brilliant borders—a Queen must be seen—a Queen must be different than the rest—a Queen must be a memory for everyone who sees her—and he always-motherless Gavin was seeing the official mother, the Queen, for the first time in person, at horse race. Gavin was forty, which made him less than half the Queen’s age, and a bit older in years than the princess Diana had lived to.

Anyone could tell you Diana had dissolved long ago from real life into ghost life, fading in that tunnel in Paris, ambulance and hospital and too-late heart surgeons dissolving her back into her stark, white, shocking dancing-with-Wayne-Sleep-onstage-to-shock-Charles dress. Anyone could tell you this was the Queen’s place, the racetrack; it would be bad manners and ridiculous to even mention Diana here. Her stylish days, her gambits were done. Her track was closed down.

If you brought me up, Diana said sweetly. What would happen? She’d heard his thought. But she was the master of double messages: she’d said brought me up as sweetly as if he’d offered to be fatherly with her, and she liked that in a sexy way.

Where are you now, he said, aloud now, looking around. He was going to say it and think it. He could hear her voice but he couldn’t see her.

Who are you looking for now, someone two seats over said to him, who was drinking something rummy, almost obscenely gold in a glass with thick ice cubes, and had heavier beard stubble than Gavin’s. Someone hoping he wasn’t sitting next to someone talking to imaginary Tinkerbelles. A dead person. Maybe the Queen then. Is she a friend of yours, now. She’s down there. Who are you betting for today?

My father, said Gavin.

Oh, your father, the man said.

And you, Gavin made himself ask, with a dip of his chin.

For a scheme for the disadvantaged in Sussex, said the man. Always looking to help someone out. Horseman yourself?

Never, said Gavin. Polo about as attractive as polio. Bad internal balance. No early lessons. No bolthole in the country. You know, the usual.

The man laughed. I like a horse, he said. Too bad I never learned to properly really rigorously ride one. They say they have a horse they’ve never named; this is its first time out. The Queen’s husband’s. Philip’s. If the filly does well they’ll name it and keep it.

But it has to have a name to run, doesn’t it? Gavin said.

Named it something like Sunny Day, just for today. Then if not much of an investment it’ll be off to the slaughterhouse as they say most do. Did you know that? There needs to be a better scheme to save them. The French, the Japanese, a half dozen other countries, they’ve taken to liking horse meat since eons ago, my impression, and most racehorses end up there. Though I don’t know if that’s the case with all the Queen’s. A horse however—consider it—is a large animal to bury, or even cremate; it’s like the Trojan horse. What do you do with it?

That’s a grim thought, said Gavin. He knew Diana had slipped off, was gone, taking her pale blue scent with her. She’d said she’d have a surprise for him at the track. She didn’t need to warn him she would never like being the left-out listener when two people spoke.

It is indeed, said the man, who underneath the striped jacket wore a pale gray vest and a pale gray hat too, and shoes of too great, Gavin thought, a shininess for such a warm day.

He had binoculars. They also looked new.

Here they come now, he said. Looks like we both got stood up. My mother was going to come but she had her usual Saturday cold. The race announcer was saying so much so fast Gavin could not make sense of his words; to blot out that confusion Gavin watched the horses, stepping out one after another, their heads bobbing heavily, looking tired, somehow, already, like weary students the first day of class dreading exams-future.

Let’s go, Diana had said. I must go. I’ll do some magic. You won’t believe what I intend to do. Gavin didn’t know where she’d gone. But the dead always played games. The man near him who wore a blue and white striped jacket was saying Sunny Day the horse who was a favorite of Philip’s was, look, a dull white with gray speckles: very unusual sight, that coloring.

Diana was at last tuning in.

Won’t believe this, Gavin, Diana said. It’s me, Sunny Day; look at the rich Loire valley of my haunches. Spring length of my leg. But lots of good muscle there too. Oh, look now—a Fiat Uno of a horse! A black car and a white Fiat Uno all mixed together. That’s my breed. Or is that me? I see some big black horses that look like the Queen’s Daimlers and Range Rovers—real taxicabs there for wherever you want to go, Gavin—can I tell you how funny it feels to have hooves? They make that sound, like ladies’ high heels—everyone knows you’re coming. I like this a lot, Gavin. Mark my words, I might show them today. Safe, safe, in a horse’s hide.

They were, all the horses, making their beautiful trudge-amble up the row leading to the boxes where they would be locked in, then begin. Their jockeys were in various forms of slouch, looking as if they did not care who won. Then they reached the starting boxes. They changed suddenly there: royal figures, on show, at war.

Time to shine, said Diana. Time for Shakespeare looking for his mother. There was a little dim- faced jockey on her back who looked as if he was always making deals with shadows. The sun was difficult for him.

I wonder how much the purse is, said the man near him, who looked as if he was going to keep his striped jacket on no matter how hot it became. He was here to suffer, to prove he could do this, be an upper-crust. He’d brag at work he’d been here; he’d not just watched it on the telly.

No idea, said Gavin. It’s probably not on a normal person’s scale.

You’re not the son of that Helyar, are you, said the man. I think I’ve seen you in photographs. The Daily Mail.

Oh, I am, said Gavin.

A wonderful novel he’s just written, said the man. But he writes a lot, doesn’t he? Probably sends you to the races while he’s busy writing, eh? Probably bought you tickets and gave you a hundred to get you out of your mansion he’s gave you next to the British Museum.

Thank you, said Gavin. Actually Knightsbridge. A flat. Very small. He’s actually trying to write one about horses. A science fiction opera. Horses and ballerinas who fly.

Horses flying? But they already do that. Muybridge’s photographs we know show that there are moments when all four hooves are off the ground, the man said. As soon as they found out you were famous Helyar’s son they upped their game.

Like rockets, said Gavin. That’s more than Muybridge. But I’m giving too much away. Sunny Day was beginning to lift her knees high. She was swinging her head. Dear Diana the visionary girl was back.

The man was replying: probably hoping Gavin would relay his words to his father the famous writer. What a thought—imagine them soaring through the sky, now, like Pegasus. But you’re making me dizzy, now. Or you might just be making this up. Why are there empty seats here? Is the Queen coming up to see you, said the man. Because you’re Helyar’s son.

Oh, just waiting for Diana, Gavin said.

Now that would be a sight, said the man, but his voice beginning to fade. It was considered impolite to mention Diana, unless you were very drunk. It was unnecessary. No one could save her. No one knew how the accident had happened in the tunnel. No one knew why the tiny white Fiat Uno which had collided with her great dark car was found burned to char in a field somewhere.

Indeed yes, said Gavin. He suddenly had a vision, at the racetrack, high in the stands: saw himself as one of his adoptive father’s dreamhorses, a horse with great front chest musculature and massive muscular wings outspread, and his long-haired sister he’d just met sitting on his back, holding the gentle reins slung beneath his tongue to control him, and their taking off to visit Helyar, Gavin’s adoptive father, on whatever planet he was on, after his death, on some other side of the sun. He would be trying to explain to this sister why he loved his adoptive father, why she should love him too. Her hair would be blowing in his face now and then, but space suits would be unnecessary, and Diana, if she saw them, would do everything she could to make his sister go.

Diana had to be the star.

As she was doing now. Now be with me, Diana’s firm voice was saying now, to Gavin.

I’m watching you, Sunny Day, Gavin said. He said this aloud. She was flying round the track. Her knees were high, high. She was like a tank. She was like a horse swimming in water which could not sink. She was artillery. She was ahead.

You’re for Sunny Day, said the man.

No, just mumbling, Gavin said. Like the name. Like her color.

Did it a lot since my own father died, said the man. Talked to myself. My mum said if I went to a racetrack and yelled things it wouldn’t be talking to myself. Could work it out. So I go now and then. Helps, does.

Yes, said Gavin. She was really talking to him now.

Don’t concentrate on him. I don’t like his jacket. Yours is alright. Watch me. Think of me, Diana said. You’re the only one who knows I’m here. As a horse.

Be back with me after the race and tell me all about it, Gavin said.

It’s not possible, Diana said. Now I want you to leave your box and go down and sit with the royal family, my fine relatives who don’t have any sense of—relay.

Gavin felt his skin go British schoolboy cold. That’s not possible, I’m not royal, he said.

You’ll be surprised how lonely they are, she said. And how thrilled they are if people just want to sit with them.

You grew up on an estate, Gavin said to her. She wasn’t answering. She was racing, swaying to the curve, showing all the dark horses she was the dark horse. But dappled like rainclouds, white and gray.

I’m heading south, said Gavin to the man. Down to the front. To see it better.

The man looked surprised and slightly offended. Oh, you’re one of the toffs. Down by your

Queen then, he said. Apparently he was quite hurt he was leaving.

Can I take your picture for your mother, Gavin said. Or your coworkers.

The man burst out laughing. No, the man said. I’ll look for his book.

Gavin felt for the badge he had in his trouser pocket, headed down the stairs, turning his long, fancy shoes with dancing curlicue wingtip lines sideways on the shallow steps to avoid stumbling. Not a day for a concussion. He could feel the imaginary hand of Diana atop his head as he worked his way down the stairs. Somehow though racing she was worried also about his falling. Playing the mother for him. Already earlier in the day laughed at him about being motherless; she knew it felt better than being pitied.

He was now at a level to work his way almost into the royal group. This made him feel like a creep, an assassin. To the security men at his left and right he patted his little paper badge that identified him as part of the hallowed about-to-be commanders of the British Empire group his father was part of.

Ah, Gavin Newsome, they said, as if they had grown up on the same street of a small village with him, instead of being attendants for the Queen and her family as they prepared to watch the Queen’s horses race.

No, Gavin Helyar, he said.

Gavin Helyar, they repeated, seemingly as happy with that name as another.

You’d like to visit the Queen, they said, in a voice of some testiness, to see if he gave wrong answer. The badge Diana had given him—had told him where to find—alright, there had been a little stealing involved—was working. He had not wanted to ask his father for the favor. All his life was indebtedness to his father for his favors.

Oh no, said Gavin. Just let me sit behind them—to enjoy being near them watching Sunny Day.

Surely my man, they said. The more the merrier to watch Sunny Day. Gavin could see their purpose. They bristled, but they also cultivated happinesses. Protective, but they made fine noises. They made Gavin want to be royal.

Indeed, said Gavin. Indeed, yes. They then passed him a tray of chocolate profiteroles with whipped cream squirting out their sides, which legend said had brought poor Andy and Sarah together; and a tray of foamy ale in plain, tall glasses, faceted as if copying jewels, extremely shiny.

Soon after there was a box of dark chocolate mints, a cut-glass bowl of strawberries. The horses were now spitting out their bits and gulping in air. He could see two rows ahead of him the pretty Victorian upsweep of Princess Anne’s increasingly delicate hair, the bright white cuff with a huge squared cufflink on it of her brother Prince Charles; Camilla’s little ratlike teeth and fancy rolled collar and brooch of multiple, secret-looking, somehow colorless stones; Philip’s spotted skin and eyes like polished agate, focusing nowhere for long. Slightly off from them was William looking like a sleepy pastry, and his sugar-candy wife expecting another royal child who would become another pastry case; his brother Harry looking like a tattered elf, with his new bride-to-be, an American who had somehow let herself be recolonized.

Sunny Day was claiming her crown. She ran like a horse who knew about the slaughterhouse and would show them all she wouldn’t have it. Nor would any of her friends. The jockey was not her driver. She was.

I’ve always told everyone, girls are just as good as boys, said Princess Anne. Look at her go.

Worth the money, said Philip. And the agony.

Perhaps, said the Queen. I generally have to see them run several times to be convinced however. But we might have a good show on our hands.

Our hour hands, said one of the security guards, the men who had led Gavin to his seat. We need to deliver these awards and purses Thursday, you know.

Oh, we know, laughed the Queen. She looked happy as a child to see the horses run, and indeed, she looked dressed up as if for her own birthday party, everything very matched and very new and a different color than anyone else wore. Like the man who’d sat near Gavin in the stands, she had binoculars.

She might be enjoying that too much, said the Queen, of Sunny Day. She’ll wear us all out.

Sunny Day was waving her head side to side even as she ran, throwing her mane in rippling movements, looking slightly side to side, wary of others. Her jockey atop her was bending ever lower, burying himself in her mane.

Making love to her properly, said Philip. The Queen looked sharply at him.

Making love to her, said Philip, again, sharper, because now Sunny Day was very much in the lead.

Love not a sport of his anymore, said one of the security men near Gavin, so low Philip could not possibly hear.

I believe she should make a rout of this race, Prince Charles said. My own horse is in here as well. Nannymaid, he said, with a face of great sweetness.

Oh, that horse of yours, said Camilla. The one you picked up almost free. A charity.

Saved her from the slaughter, said Charles.

Or becoming a delicious French meal, Camilla said with great relish, causing Charles to turn his head and stare at her for a second, one quick, brief second.

I think I am going to throw up as they say in America, said Kate the Duchess of Cambridge. She brought her hand to her middle in a staged fatigue. I’m running to the loo, she said to William. Security guards surrounded her. He got up to kiss her then settled down again in his seat next to his brother. The both of them together looked like two pastries that would stay a long time in a case and all would be afraid to buy; something about everything about them was confusing. They looked as if they wanted to go home instead of being set out in glass cases in the pastry shop, always on display, till someone pitied them and bought them and cut off their heads with the first bite. They would rather be flour in the bag or wheat in the fields, than the pastries they had to be, waiting for a hungry customer. Ah, to be marzipan in a tub, sleeping with all the other ground almonds and crystals of vanilla sugar. Ah, to be.

Let’s go down there, said William to Harry. Let’s see Sunny Day come in.

Don’t, said the Queen.

Charles was pulling back in his seat, obviously hoping his own horse would prevail, and Camilla beside him was laughing derisively at Sunny Day’s pulling ahead of Nannymaid and the other mostly dark horses, Sunny Day and Camilla together making fun of their slowness. Sunny Day owned the track today, even before the last turn, the important turn where races are decided, the tunnel formed of important last desperate moves.

I wonder who we could mate her with, said the Queen.

Oh, let her stay single, said Prince Philip.

What about you, said Prince William, to his grandmother.

Oh, don’t worry about that, I’m not to go down there, they’ve all seen too much of me already, said the Queen. Go ahead.

Sunny Day came in first, far-ahead first, and the whole crowd was shocked to see both William and Harry leap aboard her after the jockey dismounted. Thanks to the Queen and her horses and polo they were very good and fearless and natural on a horse; they had no problem leaping up. They ignored the jockey’s tiny high stirrups. William sat in the small slip of a saddle and Harry sat behind him.

Something we did all the time as a child, said William, to a microphone held up to him by someone, over the loudspeaker system.

As children, rode double on our pony, said Harry. Everyone was stepping out of the horse’s way and the horse Sunny Day was heading back toward the track and they were letting her go there, for a victory walk around. They were princes. She Sunny Day by this was double-crowned.

Gavin could see the Queen’s eyes crinkling and blinking. In the Queen’s box Kate, who had just returned, had both her hands trundled in her lap as if it was winter and her fur muff she liked to wear to photographed events was enclosing and protecting her hands. Meghan sat with icy expression. They were wives, thought Gavin, who’d never had to bear a mother-in-law’s glance, who’d been able to be mother and wife to their husbands; who’d had the whole oyster, the Oyster Card. Just as any wife he’d ever have would be similarly lucky: owning all the stage, no mother-in-law to ever meet. But thus, always, they would never be quite authentic as a wife: they’d be Wendys.

But Gavin, sitting above the royal family, was listening for Diana, his Tinkerbelle. But through some magic of transmission he instead was able to hear clearly what her boys were quietly saying to Sunny Day, their mother, the dappled race- filly. A lip-reader could only have guessed what they said.

Run, Sunny Day, said William.

Run, run, run, said Harry, his tatty sweet almost stuffed-animal-Tigger bits of orangey-red hair up like tiny precise flames in the sun and wind on the cold day.

And she flew. At least, in Gavin’s eyes she flew. To the rest of the racecourse crowd she was most likely ambling with two tall brothers somewhat awkwardly—not small-as-a-child jockeys—sitting together on her back, straying from the winner’s circle. But in Gavin’s mind and no doubt in Diana’s heart and mind she took off from the ground with the beautiful lunge of a horse as it prepares for leap, ascendance, a maneuver no other animal or man or woman can can hope to do so gracefully. The cow that jumped over the moon was a hilarious imitation. They were her suns. She would take them past the sun.

You too, she whispered to Gavin. You who waited for me. And listened for me. And didn’t call me crazy. And didn’t lust after me. And won’t. I hope.

Yes, Gavin said. I’m just a very convenient clairvoyant. But I can’t ride. I’ll just imagine it. Thanks darling. I love you.

Death waits for wonderful ones, as you the living wait for wonderful dinner. It takes us down— like the white tiger waiting for the hunter, or the hunter waiting for the tiger and his pelt, her pelt, its life. Gavin heard this in a burst. She was a novelist who’d never written. This her vainglorious words. As she rushed the track at leisure with the two famous princes, her sons, atop her. The jockey like a bad appointed suitor waited as he must. With a terse, used-to-being- used smile.

Mostly, Gavin decided, the boys, now grown men, looked strangely graceful; many would believe this had been planned. They boys themselves would tell people they didn’t know why, but they had to ride Sunny Day. The jockey had stood back, offered them the reins—Gavin could already hear their excuses. But they knew somehow it was their mother.

Diana his Tinkerbelle was goodbyeing. Here we come to Jupiter, she said. Here we come to Mars. Good luck, little Kate with your fur muffs and your photoshoots. Good luck little Meghan with a thoroughbred’s stick legs and looking like another slim-hipped Wallis, outdoing Kate and Pippa in the slim-hips department. What a wonder any of you can bear. Good luck drowsy chinaware Camilla and Charles. Good luck big stuffed animal the Queen and that fellow who keeps hanging around like a soothsayer, Prince Fill Up the Glass Philip. I’m toasting to you. I’m a horse. Do you love me now?

All this was for Gavin, the witness, the medium.

The poor princes could only feel and know and hear the clop of her hooves. How could you hear your mother’s thoughts? That is the one thing no child can ever know.

They should be riding onward, thought Gavin, in his father’s space-horse ballet, half opera, where no horses would ever be put to death once past their usefulness, where they would live till natural dying day, as Diana should have.

Where chariot men would fight and battle for their loyal creatures who could carry them galaxy to galaxy, to the planets where the old Greek ideals were re-realized and rebegun, but without the old Greek words and dreams attached: where new stars would need new names. Where Diana’s name was changed and new.

Yes, thought Diana back to him, but the words had such a high wobbly noble sound: she was high-up disappearing, flying away. He was only a medium. Sunny Day was a lucky horse.

His phone rang in his left pocket. It was his father. I can’t write another chapter without you, the message was. Get home. I don’t know why. You have to be here to get me started. I’m stuck.

Sure Dad, said Gavin, in type, to his phone, which would, like a good servant, send the message to his father.

*

Rebecca Pyle lives in Salt Lake City, where until recently she had an art studio between two Salt Lake City train depots, the Rio Grande and the Union Pacific, enormous old structures blocks apart. Rebecca’s poems, paintings, and stories are in Die Leere Mitte, New England Review, Indian Review, Watershed Review, Litro, Penn Review and Map Literary. She also has a poetry chapbook: The Underwater American Songbook (Underwater New York, 2018). And, an art website: rebeccapyleartist.com.