Excerpts from “The Cloud in Trousers” by Vladimir Mayakovsky (translated from the Russian by David Lehman)

The Cloud in Trousers

(From Part One)

Hey!

Gentlemen!

You who,

next to me,

are rank amateurs

in the realms

of sacrilege,

mischief,

and mayhem —

have you laid eyes on

the most terrifying thing

in the world –

my face

when I am totally calm,

cool and collected?

I fear

my ego

isn’t big enough

for the rest of me

which

is struggling

to emerge

as a full-born youth

from a Madonna’s womb.

*

Hello!

Who’s there?

Mama?

Mama!

Your son is sick, magnificently so.

Mama!

His heart’s on fire.

Tell his sweet sisters

in all of Russia there’s nowhere

he can take refuge.

The words he spits out,

the jokes he cracks,

flee from his scorching mouth

like naked women

jumping out the windows

of a burning brothel.

The stink of burnt flesh is in the air.

The fire brigade drives up

in a shiny new red truck,

the men with their helmets on.

But no hobnailed jackboots here.

Tell those guys to tread softly

when a heart’s on fire.

Look, I’ll show you what to do.

I’ll pump buckets of tears from my eyes.

I’ll save the one last survivor,

the thirteenth apostle,

who lives in my heart

and wants to leap to his freedom.

In vain.

You can’t leap out of your heart.

From the crack of the lips

on my smoldering face

the cinder of a kiss struggles to escape.

Mama!

I can’t sing!

In the chapel of my heart the choir’s on fire!

Figurines the shape of letters and numbers

rush out of my skull

like kids bursting out of a schoolhouse in flames.

And as the blaze quickly spreads

I command you to moan

to the centuries, if you will,

my final intimate yell: I’m on fire!

***

(From Part Three)

All of a sudden

the clouds rioted

in the sky like

workers on strike,

and thunder

came out of the nostrils

of the heavens, the sky flinched,

and even Bismarck had to stand down.

Out of the clouds came an arm,

a hand reaching into the Café

where I sat and wrote,

and that hand was female,

lovely but explosive as a gun.

***

(From Part Four)

Maria! Maria! Maria!

Open up.

It’s cold out here, and the streets are scary.

No? Would you rather see me freeze,

whipped by the wind, stripped,

my skull devoid of my teeth?

Maria, look! I’m shivering! I’m shaking!

and the rain is pelting the pavement,

pelting all of us,

beggars, junkies, winos, bums,

like tears

from the eyes of the drainpipe waterfall.

And thus the rain licked our feet

all of us except for the fatsos

stuffed with goose liver

and with an apple in their mouths

riding in the back seats of expensive carriages.

*

Maria!

Open up.

The mob is breathing down my neck.

Look, they’re attacking my eyes with hatpins!

I’m in.

Maria, I want you

to ignore whatever they say about me

I may have kissed a thousand girls

but you’re this madman’s favorite,

for I’ll gladly admit I’m a mad man,

mad about you.

Maria, I’d love it if you

and I took off all our clothes

and lie, naked and shameless,

or scared, if you prefer,

in bed.

Let me kiss you on the mouth.

On this May day come live with me

in the April of my heart.

Maria!

Poets write sonnets

to the souls of their lovers,

but I am every inch a man

and I want your body as much as

a devout Christian beseeches the Lord

to “give us this day our daily bread.”

Maria,

I confess I’m afraid I’ll forget your name

as a poet is afraid he’ll forget le mot juste

which he has looked for all his life,

the word born in a night to perish in a night,

while the soul glowed in rays of light.

Maria,

I promise you I will love your body

as much as a wounded veteran loves

his one remaining leg.

No? Why no?

But you say no.

Damn.

So once again I’ll have to carry my heart away

as a dog nurses the paw that was crushed by a train.

———————-

Облако в штанах

Эй!

Господа!

Любители

святотатств,

преступлений,

боен, —

а самое страшное

видели —

лицо мое,

когда

я

абсолютно спокоен?

И чувствую —

«я»

для меня малó.

Кто-то из меня вырывается упрямо.

Allo!

Кто говорит?

Мама?

Мама!

Ваш сын прекрасно болен!

Мама!

У него пожар сердца.

Скажите сестрам, Люде и Оле, —

ему уже некуда деться.

Каждое слово,

даже шутка,

которые изрыгает обгорающим ртом он,

выбрасывается, как голая проститутка

из горящего публичного дома.

Люди нюхают —

запахло жареным!

Нагнали каких-то.

Блестящие!

В касках!

Нельзя сапожища!

Скажите пожарным:

на сердце горящее лезут в ласках.

Я сам.

Глаза наслезнённые бочками выкачу.

Дайте о ребра опереться.

Выскочу! Выскочу! Выскочу! Выскочу!

Рухнули.

Не выскочишь из сердца!

На лице обгорающем

из трещины губ

обугленный поцелуишко броситься вырос.

Мама!

Петь не могу.

У церковки сердца занимается клирос!

Обгорелые фигурки слов и чисел

из черепа,

как дети из горящего здания.

Так страх

схватиться за небо

высил

горящие руки «Лузитании».

Трясущимся людям

в квартирное тихо

стоглазое зарево рвется с пристани.

Крик последний, —

ты хоть

о том, что горю, в столетия выстони!

***

Вдруг

и тучи

и облачное прочее

подняло на небе невероятную качку,

как будто расходятся белые рабочие,

небу объявив озлобленную стачку.

Гром из-за тучи, зверея, вылез,

громадные ноздри задорно высморкал,

и небье лицо секунду кривилось

суровой гримасой железного Бисмарка.

И кто-то,

запутавшись в облачных путах,

вытянул руки к кафе —

и будто по-женски,

и нежный как будто,

и будто бы пушки лафет.

***

Мария! Мария! Мария!

Пусти, Мария!

Я не могу на улицах!

Не хочешь?

Ждешь,

как щеки провалятся ямкою,

попробованный всеми,

пресный,

я приду

и беззубо прошамкаю,

что сегодня я

«удивительно честный».

Мария,

видишь —

я уже начал сутулиться.

В улицах

люди жир продырявят в четырехэтажных зобах,

высунут глазки,

потертые в сорокгодовой таске, —

перехихикиваться,

что у меня в зубах

— опять! —

черствая булка вчерашней ласки.

Дождь обрыдал тротуары,

лужами сжатый жулик,

мокрый, лижет улиц забитый булыжником труп,

а на седых ресницах —

да! —

на ресницах морозных сосулек

слезы из глаз —

да! —

из опущенных глаз водосточных труб.

Всех пешеходов морда дождя обсосала,

а в экипажах лощился за жирным атлетом атлет:лопались люди,

проевшись насквозь,

и сочилось сквозь трещины сало,

мутной рекой с экипажей стекала

вместе с иссосанной булкой

жевотина старых котлет.

*

Мария!

Звереют улиц выгоны.

На шее ссадиной пальцы давки.

Открой!

Больно!

Видишь — натыканы

в глаза из дамских шляп булавки!

Пустила.

Детка!

Не бойся,

что у меня на шее воловьей

потноживотые женщины мокрой горою сидят, —

это сквозь жизнь я тащу

миллионы огромных чистых любовей

и миллион миллионов маленьких грязных любят.

Не бойся,

что снова,

в измены ненастье,

прильну я к тысячам хорошеньких лиц, —

«любящие Маяковского!» —

да ведь это ж династия

на сердце сумасшедшего восшедших цариц.

Мария, ближе!

В раздетом бесстыдстве,

в боящейся дрожи ли,

но дай твоих губ неисцветшую прелесть:

я с сердцем ни разу до мая не дожили,

а в прожитой жизни

лишь сотый апрель есть.

Мария!

Поэт сонеты поет Тиане,

ая—

весь из мяса,

человек весь —

тело твое просто прошу,

как просят христиане —

«хлеб наш насущный

даждь нам днесь».

Мария — дай!

Мария!

Имя твое я боюсь забыть,

как поэт боится забыть

какое-то

в муках ночей рожденное слово,

величием равное Богу.

Тело твое

я буду беречь и любить,

как солдат,

обрубленный войною,

ненужный,

ничей,

бережет свою единственную ногу.

Мария —

не хочешь?

Не хочешь!

Ха!

Значит — опять

темно и понуро

сердце возьму,

слезами окапав,

нести,

как собака,

которая в конуру

несет

перееханную поездом лапу.

VLADIMIR MAYAKOVSKY (1893-1930) was a brash poet, playwright, artist, and actor, who became a leading Russian Futurist. Having made his mark with such long poems as “The Backbone Flute” and “The Cloud in Trousers,” he lent his talents to the Bolshevik Revolution, even as he began to chafe against the constraints of Soviet orthodoxy after completing two satirical plays (The Bedbug and The Bathhouse) lampooning government bureaucracy. He traveled to America in 1925 and to Western Europe in 1928. In 1935, five years after Mayakovsky took his own life in Moscow, Stalin praised his work, leading to his rehabilitation and canonization as the “Poet of the Revolution.”

DAVID LEHMAN is the founder and editor of The Best American Poetry series. He is the author of several collections of poems, including Poems in the Manner Of, New and Selected Poems, Yeshiva Boys, When a Woman Loves a Man, and The Daily Mirror: A Journal in Poetry. Lehman’s work has been translated into 16 languages. His books of prose include Sinatra’s Century: One Hundred Notes on the Man and His World, The State of the Art: A Chronicle of American Poetry, 1988-2014, A Fine Romance: Jewish Songwriters, American Songs, and The Last Avant- Garde: The Making of the New York School of Poets. He lives in New York City and Ithaca, New York.

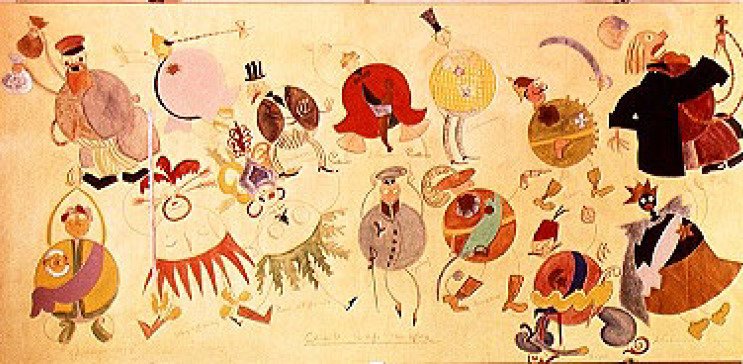

Image: Costume Designs for Misteriya-Buff (1919) by Vladimir Mayakovsky, pen and ink and watercolor on paper.

© LIT Magazine Issue #33, 2019