Four Poems by Bronka Nowicka from "To Feed the Stone" (translated from the Polish by Katarzyna Szuster) Drawings by Lula Bajek

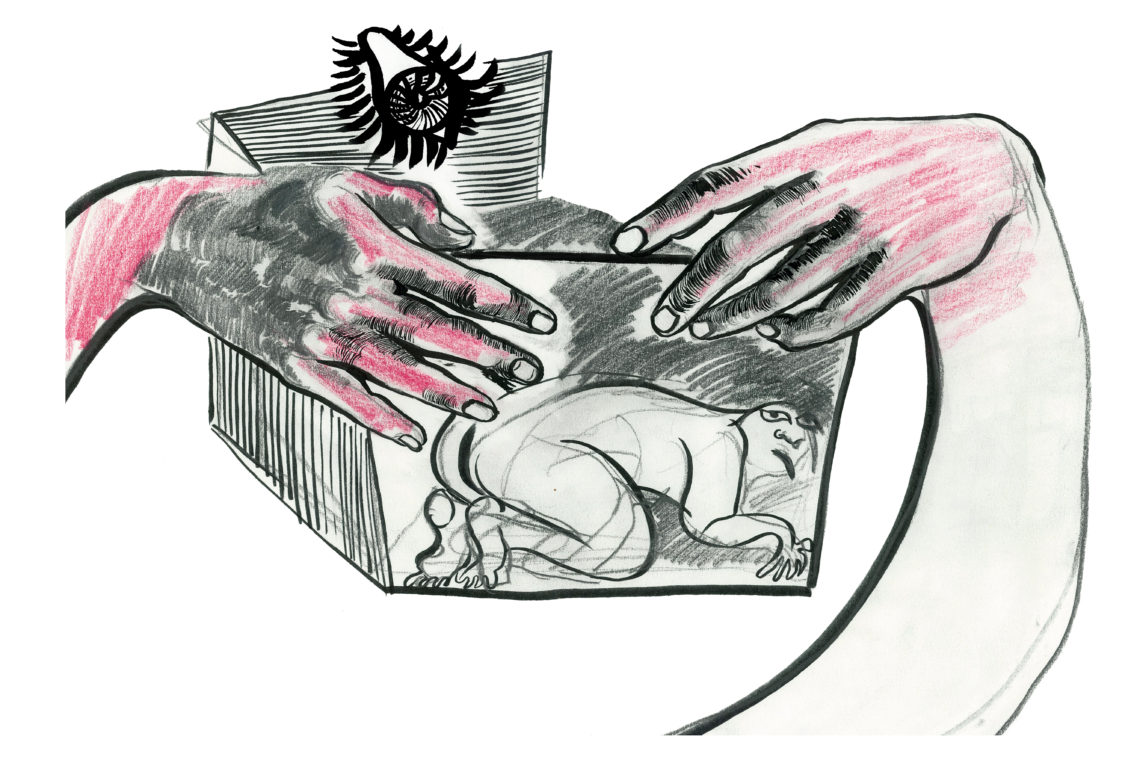

Box

Mother doesn’t know that heaven exists. She’s getting a double chin from looking down. Her head, as heavy as an iron, presses that fold down.

Father keeps getting in mother’s way. He’s short. To reach grown-up things, he needs to stand on his tippy-toes or get a chair. He just moved it by pressing his belly against the seat. Now he points to the cushions. He needs them stacked to reach the table. He clambers up, props his elbows on the counter covered with an oilcloth, next to a spoon, a fork and a knife. Father opens his mouth while mother pours in soup, one spoonful at a time. She inserts potatoes and meat chopped in cubes into a pink hollow with a hungry fledgling.

He eats up. She praises him for chewing with his mouth closed. Mother uses one hand to do the work, the other to hold up her head, which watches father: a pretty boy. She could keep him in a box. She’d make holes in the lid. Inside, she’d put some cotton fluff, feathers, wool, pieces of lignin. There’d always be crumbled sponge cake in one corner. Sometimes she’d take him out to have a look.

The pretty boy is done eating. She wipes his chin with her finger which she’s just licked.

– Go play now – heavy wife says to short husband.

I’m sitting under the table, watching the soles of his feet, which are dangling above the floor.

Pudełko

Matka nie wie, że istnieje niebo. Od patrzenia w dół robi się jej drugi podbródek. Zaprasowuje tę fałdę głową ciężką jak żelazko.

Pod nogami matki kręci się ojciec. Jest krótki. Po dorosłe rzeczy wspina się na palce albo przystawia sobie krzesło. Właśnie je odsunął, prąc brzuchem na siedzenie. Teraz pokazuje na poduszki, trzeba mu je podłożyć, żeby dosięgnął do stołu. Gramoli się opiera łokcie o blat z ceratą, na której leżą łyżka, widelec i nóż. Ojciec otwiera usta, a matka – łyżka po łyżce – wlewa w nie zupę. Wkłada ziemniaki i pokrojone w kostkę mięso do różowej dziupli z głodnym młodym.

Je ładnie. Chwali go, że z zamkniętą buzią. Jedna ręka matki pracuje, druga podpiera głowę, która przygląda się ojcu: malowany chłopiec. Trzymałaby go w pudełku, zrobiła dziury w wieczku. Do środka dała watę, pióra, wełnę, porwaną na strzępy ligninę. W róg sypała pokruszone biszkopty. Czasami brała do ręki i oglądała.

Malowany chłopiec skończył jeść. Wyciera mu brodę poślinionym palcem.

– Idź się pobaw – mówi ciężka żona do krótkiego męża.

Siedzę pod stołem i przyglądam się podeszwom, którymi on nie może dosięgnąć podłogi.

*****

Fork

– We used a fork to brush our hair and we cooked noodles in a kettle. If one of us, and there were four girls, didn’t brush her hair in time, she had to wait until her sister took all the noodles out of the kettle with that comb of ours. When the kettle stopped being a noodle pot, you could boil water for tea.

My doll was a rolling pin. There was no butter or sugar so the pin was useless. My aunt burned her eyes out with a wire heated over a candle. She put a rag on her head and sewed her a dress. But we didn’t have a hammer. When you had to nail a shoe together because it came apart, the doll was undressed and when naked, she was a hammer.

You waited through air raids in the tombs. The gravestones were gorgeous, like houses with basements. You had to take stairs. When one casket was bricked up, it was low and you could sit comfortably. If it was higher – because the caskets were stacked up – it was harder. But the grave digger would take us to such a grave where a mother with four kids could fit. Inside, I remember, the walls were painted blue and white. Our apartment’s walls weren’t that clean, who would think of repainting walls during the war? You didn’t paint. Women made themselves up – they did their eyebrows with coal and lips with a beet.

The neighbor comes by every day. She drinks her coffee and lets out old times that stick to her like dregs on the bottom of a glass. She pours them over for the hundredth time. The memories are getting thinner but they can still be brewed. The child likes to listen – it learns about life. It already knows: the war is when objects lose their mind. It’s afraid of eating with a fork. It keeps the fork away from its hair.

Widelec

– Myśmy się czesali widelcem, kluski gotowali w czajniku. Jak się która, bo nas było cztery, nie uczesała w porę, to czekała, aż druga wyciągnie tym naszym grzebieniem cały makaron z czajnika. Jak czajnik przestawał być garnkiem na kluski, dopiero się wstawiało wodę na herbatę.

Lalkę miałam z pałki do ucierania ciasta. Nie było masła, cukru – pałka była na nic. Ciotka wypaliła jej oczy drutem rozgrzanym nad świeczką, na głowę dała gałgan, uszyła sukienkę. Ale myśmy nie mieli młotka. Jak trzeba było wbić gwóźdź w but, co się rozlazł, lalkę się rozbierało i taka goła to był młotek.

Naloty się przeczekiwało w grobowcach. Piękne te pomniki, jak domki z piwnicami. Po schodkach się schodziło. Jak była jedna trumna zamurowana, to było nisko, było wygodnie siedzieć. Było wyżej – bo trumny stawiali piętrowo – było ciężko. Ale to już grabarka nas prowadziła do takiego grobu, gdzie mama z czwórką dzieci się ulokowała. W środku, pamiętam, ściany pomalowane na niebiesko, na biało, w mieszkaniu myśmy tak czysto nie mieli, bo kto by w wojnę malował. Nie malowało się. Kobiety się malowały – brwi węglem, usta burakiem.

Sąsiadka przychodzi codziennie. Pije kawę i wypowiada z siebie stare czasy, które zalegają w niej jak fusy na dnie szklanki. Zalewa je setny raz. Wspomnienia są coraz cieńsze, ale ciągle dają się zaparzyć. Dziecko lubi ich słuchać – uczy się o życiu. Już wie: wojna jest wtedy, gdy przedmioty tracą rozum. Boi się jeść widelcem. Trzyma go z daleka od włosów.

*****

Sink

Father is growing up. It’s not only that mother has started to shave him and buy him larger size shoes. It’s that he wants out. But he doesn’t know how. He puts off figuring it out but he’s trying on his body appropriate for the occasion.

He stands in front of the mirror, wearing out his comb too fast. Maybe he thinks that the direction towards which he’ll comb his hair will also determine the course of other things. He does his part as if he were creating a planet. He destroys it and another one emerges. More to the left.

Having built many a flimsy worlds, father creates the right one on his head, puts away the comb and rests. Later he moves on to stroke his belly but his hands are too small to iron out all that skin. They look like a doll’s hands attached with a rubber band to the buttons on his shirt’s sleeves.

Feeling that he won’t achieve more than what has already been achieved, father tippy-toes to the door. It won’t open even though he presses on the handle with his elbow as hard as he can.

Mother washes a pot, father looks at the stream being sucked by a whirl on the bottom of the sink. He envies it that it can escape this house. He too would like to disappear down the drain, clinging to something so small that they would both pass through the metal eye. He can see himself swimming in the warm conch of the freshly drained pasta, digging his nails into an apple stem. But there is nothing in the greasy sink apart from water. And you can’t grab onto water.

Zlew

Ojciec nam dorasta. Nie w tym rzecz, że matka zaczęła go golić i kupuje mu większe buty. Chodzi o to, że on chce do świata. Tylko nie wie jak. Myślenie o tym odkłada na później, ale już przymierza ciało odpowiednie na tę okazję.

Stoi przed lustrem i zbyt szybko zużywa grzebień. Może sądzi, że kierunek, w którym uczesze włosy, wyznaczy też bieg innych rzeczy. Robi przedziałek, jakby stwarzał planetę. Niszczy ją i powstaje nowa. Bardziej na lewo.

Po zbudowaniu wielu marnych światów ojciec dokonuje na głowie tego, który jest właściwy, odkłada grzebień i odpoczywa. Potem bierze się za gładzenie po brzuchu, ale ręce są zbyt małe, żeby wyprasować tyle skóry. Wyglądają jak dłonie lalki doczepione gumkami do guzików przy rękawach koszuli.

Czując, że nie zrobi więcej ponad to, co zostało zrobione, ojciec wspina się na palce i idzie do drzwi. Nie chcą się otworzyć, mimo że z całej siły naciska łokciem na klamkę.

Matka myje garnek, ojciec patrzy na strugę, którą wciąga wir na dnie zlewu. Zazdrości jej, że może uciec z tego domu. On też chciałby zniknąć w odpływie, uchwycony czegoś tak małego, że razem przeszliby przez metalowe oko. Widzi siebie płynącego w ciepłej muszli dopiero co odcedzonego makaronu, wbitego paznokciami w ogonek jabłka. Ale w tłustym zlewie nie ma nic oprócz wody. Wody nie można się złapać.

*****

Windowsill

Before taking their place in line, the women sit their children up on the windowsills. At the butcher’s, there are large windows, from which flies dribble. They fall off the glass from overeating and old age. They lie and dry up. You can do a number of things with flies. You can arrange the ones with shiny wings like a necklace. You can aim the fat ones at the skinny ones, knock them onto the floor. I have a handful of them. The women peck at it. They want to eat the flies out of my hand with their looks. The women look a lot like hens. They shuffle their feet though they’re not going anywhere. They stretch and lower their necks to see the meat tossed on the stump. Heads up: the half-carcass is dismantled. Head down: metal marbles rattle in purses. The women scavenge for change with their claws.

– Go on, keep–keep-keep moving.

They get: legs, lungs, hearts.

– Whose? – asks a boy who got tired of counting flies.

Mesh nylon bags are stretching. The stomachs and breasts are pushing the backs.

– Keep-keep-keep moving.

The ones at the top of the line can see the prices – “how much-much-much?”, they pass it along to the blind rest. A brood hen wants to jump the line. She has a sizable egg under her dress.

– Let her through, what if she lays it here?

I decide I will never become a woman. Even if my breasts come out, with time, they will fall out like milk teeth.

Parapet

Kobiety, zanim wcisną się w kolejkę, sadzają dzieci na parapetach. W mięsnym są duże okna, z których kapią muchy. Odpadają od szyb z przejedzenia i starości. Leżą i schną. Z much można dużo zrobić. Te z błyszczącymi skrzydłami układać jak korale. Tłustymi celować w chude, strącać na podłogę. Mam ich pełną garść. Kobiety ją dzióbią. Patrzeniem chcą mi wyjeść muchy z ręki. Kobiety są bardzo podobne do kur. Przebierają nogami, chociaż nigdzie nie idą. Wyciągają i opuszczają szyje, żeby widzieć mięso rzucane na pień. Głowy w górę: rozbierają półtusze. Głowy w dół: pstrykają metalowe kulki przy portmonetkach. Kobiety wygrzebują drobne pazurami.

– Dalej, po-po-po-suwać się.

Biorą: nogi, płuca, serce.

– Czyje? – pyta chłopiec, któremu znudziło się liczenie much. Rozciągają się siatki z nylonowej przędzy. Brzuchy i piersi popychają plecy.

– Po-po-po-suwać.

Pierwsze w kolejce widzą ceny – „po-po-po ile” podają do tyłu ślepej reszcie. Kwoka chce bez kolejki. Ma pod sukienką pokaźne jajo.

– Przepuśćcie ją, jeszcze nam tu zniesie.

Postanawiam, że nigdy nie będę kobietą. Jeżeli nawet wyrżną mi się piersi – z czasem wylecą, jak mleczne zęby.

*****

BRONKA (BRONISŁAWA) NOWICKA is a Polish theatre and TV director, screenwriter, poet, and interdisciplinary artist. She is a graduate of the National Film School in Łódź, Poland, and the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts. Her literary debut, Nakarmić kamień (To Feed the Stone) was awarded the 2016 Nike Literary Award and the Złoty Środek Poezji (Golden Mean of Poetry) award. In 2017, she was a laureate of the New Voices from Europe project.

BRONKA (BRONISŁAWA) NOWICKA is a Polish theatre and TV director, screenwriter, poet, and interdisciplinary artist. She is a graduate of the National Film School in Łódź, Poland, and the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts. Her literary debut, Nakarmić kamień (To Feed the Stone) was awarded the 2016 Nike Literary Award and the Złoty Środek Poezji (Golden Mean of Poetry) award. In 2017, she was a laureate of the New Voices from Europe project.

KATARZYNA SZUSTER is a translator. She earned her M.A. in English studies from the University of Łódź, Poland, and was a lecturer at the Department of Foreign Languages, University of Nizwa in Oman. She has translated various Polish poets into English, such as Miron Białoszewski, Justyna Bargielska, and Bronka Nowicka. Her translations have been published in Aufgabe, Free Over Blood, Moria, Biweekly, Words without Borders, diode, Toad Press, Berlin Quarterly, Seedings, and Tripwire.

Artwork by LULA BAJEK, Polish illustrator and drawer. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. Her accomplishments include the artistic project entitled The Black Sun. She spent two years in China learning traditional Chinese painting and now lives and works in Warsaw.