Global Voices Interviews *Poland* Bronka Nowicka and Katarzyna Szuster in conversation with LIT's JP Apruzzese

The Polish version of this interview appeared in Biuro Literackie on 23 March 2020

Every so often a writer comes along who shows us what literature can and perhaps is meant to do — offering not so much a different perspective as a different way of seeing. A writer whose work inhabits a space undetermined by convention, trends, topics of current interest, unafraid to put aside the noise of daily life and explore the unnoticed – unseen because ignored – life that is nevertheless fully within our grasp. A writer who captures the human by engaging the beings that share the world with us and bringing forth their voice. Bronka Nowicka is a mystic writer, poet, and filmmaker who converses with objects so that we can hear and understand what they are telling us. Hers is a world of myth – our own – in deep conversation with science and with our time.

I am seated at my desk in my childhood home in Jersey City surrounded by objects of memory. Each has its own story, each harbors layers of meanings, some familiar, others hidden. These objects, like me, are living in a time of pandemic, in its domain of anxiety and fear, through a human crisis, and like me they too will change because of it and become something different, and perhaps not immediately recognizable. Not far from me, thousands of miles away in Lodz, Poland, Bronka Nowicka and Katarzyna Szuster, her gifted translator, are in separate places with different surroundings but fully here to talk about the permanence of myth, the creative process, and the art of translation.

***

Bronka Nowicka

The Permanence of Myth

As we’re in different surroundings, can you begin by describing the setting and place of this interview. Where are you as you answer these questions? (This can be literal or imaginary).

Bronka Nowicka (BN): This is a difficult and beautiful question because it essentially touches on a secret. I am in my body now – in this mobile observatory, dressed in an old sweater, sitting with a cup of coffee in the studio. The body looks around: on the left there are shelves with books; on the right a sofa where the dog is lounging. A picture of the fourteenth Dalai Lama hangs on the wall and a photograph taken from a plane’s window: the clouds are a herd heading somewhere. On the desk there are flowers: daffodils and hyacinths. Next to them, several stones – they are probably billions of years old. When my body moves the stones across the desktop, I am by the sea and I’ve just picked them up from the sand. The act of remembering stratifies and multiplies me. I no longer exist in one place alone. Before I finish answering your questions, I will have switched places many times without leaving my chair. I will be shifting to the past, looking into the future. The mystery of memory fascinates me, as does the possibility to imagine what may happen. But the picture outside my window is almost still. Things are motionless, except for branches, birds, the yellow light. The trees have buds; the pigeons are landing softly on roofs; it’s sunny. However, if the landscape had a psyche and its structure resembled that of a human, I would say that its ‘peace’ is only apparent. Something apocalyptic seeps into the unconscious of this image as if the world were starting to feel its decline. This experience is probably a projection of my fears onto the landscape. Or an expression of melancholy, the symbols of which are both the color yellow and the sun, only they’re black.

Creation is not a decision preceded by negotiations with oneself, but a necessity.

You have gained the admiration of your peers and won awards in two distinct fields. You are a master of two mediums and a multi-disciplinarian. Can you tell us about your trajectory as an artist, writer, and filmmaker?

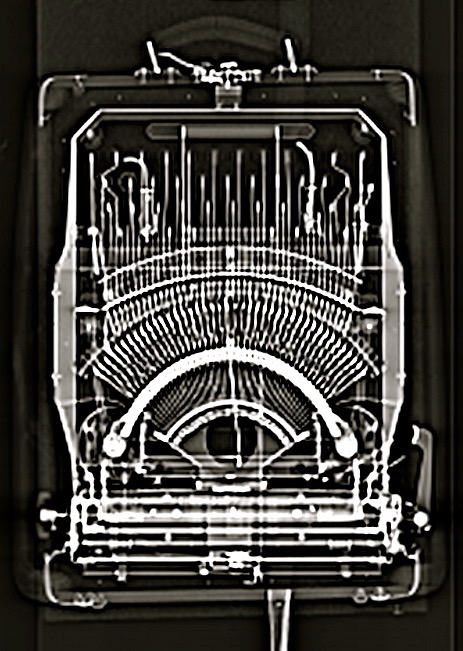

BN: I studied directing at the National Higher School of Film, Television and Theatre in Lodz. I completed postgraduate studies in the interdisciplinary studio at the Painting Faculty of the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow, where I was a doctoral student before defending my thesis at the Faculty of Graphic Arts and Media Art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Wroclaw. I have always set the bar high for myself. With a narcissist’s chip on my shoulder, I raced with myself to deserve respect, recognition and love. This race distracted me from creation. I gained strong artistic tools but didn’t have time to use them. Driven by ambition and self-doubt, I was more a conqueror than a creator. I spoke rarely, though what fascinated me had crystallized early on: difficult existential experiences, death, melancholy, the domain of memory, relationships between humans and their objects; language and its connections to memory; relationships between memory with image. Creatively, I wasn’t very active. I gained more skills. Topics were ripening. One day, spurred by painful experiences, I realized creation is not a decision preceded by negotiations with oneself, but a necessity, and I opened myself to expressing what I felt. It turned out that although I could use tools belonging to one area, I was more eager to mix the contents of various ‘toolkits’: when writing – I paint with words, create sequences of scenes, assemble a story or a book of poetry. While working on videos – I write, I introduce language into the picture using sound or figurative marks. I am also keen on looking for means of expression in fields seemingly foreign to art: I use a computer tomograph as a film and graphic tool, creating works of a transgraphic nature.

And how do you see the connection between them?

BN: Relationships between images and words are inspiring to me. They share a history of loss, one of the first that changes a person’s internal landscape. At the beginning of their lives, people don’t speak, but they are not dumb – they babble. Babbling is not a suburb of a language. It connects sounds typical of everyone. The phonic abilities of babies have no limits. A several-month-old infant, regardless of the place they are born, produces a series of sounds present in every language and vernacular. What appears to adults as daunting acrobatics of the speech apparatus is meaningful play for a baby, confirming their participation in the articulation universe. An infant, not using any language, remains in the paradise of being able to master each of them. But as soon as they start reaching out for one of them, they are banished. All that comprised babble is taken away from the child right behind the gates of paradise. Entering the exile land – the territory of native language – they lose their articulatory omnipotence and for a while they grow silent. Later, they work hard on the first word because each of the previously known sounds had become foreign. Phonic shamanism and pre-linguistic miracle cease; now begins the toil of sandwiching meaning into audible forms. This loss is followed by another, equally significant. By living in language, the child loses access to all internalized images they had accumulated before this change. By becoming a communication tool, speech begins to perform the function of a memory architect and bricks up the door to what was collected in it at the beginning of life. The first memories available to us are static images. They come from the period of speech’s beginning, the era of limited vocabulary. As its range grows and the child uses it more efficiently, the impressions begin to take on the character of scenes and episodes: they flow, creating sequences of events. This happens when the child is already able to look at the past by means of language: they can reminisce. The ability to see with words changes the nature of memories. A person doesn’t have access to memories they put away earliest because they were not recorded in language. A language cuts off access to the beginnings of our own stories preserved in images. Perhaps this is the root cause of the myth of antagonism between pictures and words; although, in fact, they share a strong bond based on an act of co-creation. A language, though it seems to be thinking material, isn’t sufficient for it by itself; it supports visual thinking. Images in memory would be immobile if they weren’t propelled by language. From the moment they are linked by the story of loss, word and image have supported each other like those who have lost their ancestors but can now lean on their successors. Scientists, such as Benjamin K. Bergen, have described another relationship between language and image. They call it ‘embodied simulation.’ When I say or write the phrase: “a polar bear crawls across the snow,” how will you decode the meaning of the sounds or characters? How will you understand what I’m talking or writing about? It mostly activates your brain’s center responsible for vision – you will imagine a scene with a bear crawling across the snow. This will mobilize your center responsible for hearing – the snow will creak; smell – you will bring out the ozone, the frosty scent of ice; the center responsible for touchwill activate – you will feel your own skin rubbing against the white surface. This is how embodied simulation works. A language is a system of encoded images (sounds, movements, smells, tactile, taste sensations) that creates a synesthetic, the most advanced and oldest cinema – the cinema in the human mind.

By becoming a communication tool, speech begins to perform the function of a memory architect and bricks up the door to what was collected in it at the beginning of life.

In your work, be it stories or film, objects and inanimate things are very much alive and part of the world and existence in a deeply phenomenological and holistic sense. How did you come to this perspective?

BN: My interests are focused on relationships between people and things. Behind objects are people, stories and memory. In the student short films I directed, an object was not an actor’s prop, but an equal protagonist. It was subject to impersonation, symbolized the deceased or made them present; it brought back memories. After graduation, I started working in theater. All the performances I directed featured motifs related to objects: consumer addiction to things, entering into relationships with them in search of substitutes for interpersonal relations. Later, when my work began to focus on photography and video, I created series in which I used things to portray their owners and create self-portraits. I also treated objects as peculiar timepieces. I measured time with artifacts – collecting them or tracking the process of their depletion, destruction, and metamorphoses of matter. I started using objects as a medium for documenting events, including meetings with other people. Dried, used up tea bags – which I tagged with dates, time of day, and events related to the act of drinking tea – were a kind of diary. Brewed tea bags – emptied of tea leaves and filled with photos of people with whom I drank tea – became aesthetic documents of get-togethers. What is it about things and their relationship with people that touches me, hurts me and interests me so much? I assume each thing has a human dimension because of its existence in the human world. This means the world of objects is a theatrum in which the world of the human is reflected. I’m interested in what is human – that’s what I want to do in my work. However, I choose a thing to be the main protagonist of my work. Why? Because I find the sense of tragedy evoked by images of things equally – if not more – intense than that which is manifested directly by human fate and the mortal body. The tragedy of things lies in the fact that they extend someone’s or something’s life only by a few steps. Whether a thing that outlives its owner and becomes his or her representative, or a thing that otherwise preserves the past – both eventually die. However, before the matter wears out and falls apart, it remembers, symbolizes, makes itself present. By speaking of the spiritual through the material, the living through the dead, treating a thing as a protagonist that is more often visible in the matter of the work than a human – who is an equal protagonist – I can talk about humanity without the pathos arising from the directness of portrayal.

Your stories such as To Feed the Stone, The Void, and Terra Memoria read like and contain the imagery of myth and fables and allegory. And yet they appear to be designed for our own time, conveying a deep sense of loss and the failure of memory and of language to convey meaning. Can you explain your creative approach to storytelling?

BN: As a human, I’m hungry for myth. I’ve always had a sense of lack. Feelings of emptiness, loss, hunger were very strong. Initially, I thought this lack could be satisfied by feeding my ambition, self-love, my stomach and eyes. I hoped to alleviate my hunger would through a romantic relationship, continuous work, and knowledge. I was wrong. For our ancestors, myth was not only a form for describing the world, its interpretation, or a map tracking the paths of protagonists – authentic or imaginary. Myth was alive and served to nourish the psyche. Anchored in the collective unconscious, it allowed one to be in touch with one’s soul and the self. It helped one to see connections between people, beings, entities, and phenomena. It linked the dark zone, the Shadow with the conscious area. It drew the line between the living and the dead. Tamed taboos. It brought us closer to the mysteries. It warned against threats. Created symbols. It was a pattern of conduct. It gave hope and sublimated. I’m hungry for myth as a nutritious, inspirational substance that boosts and transforms the spirit. It’s not only hunger that draws me to myth as a literary formula, but also a feature of myth, which I could call universalism. I’m attracted to such narratives. I’m not fond of ad hoc art, literature ‘for today,’ which is only invested in what’s current, prioritizing timeliness, reporting, involvement, a discovery of new diction, competition for thematic and stylistic inventiveness. I’m interested in fiction only if it’s a personal and, at the same time, highly universal, metaphorized and symbolic interpretation of the world and relationship with its elements, and not merely their realistic photography. That is why I turn to myth, fairy tale, parable, allegory, poetic language and rich imagery. In doing so, however, I try to talk about this world and its shortages, which I feel as my own. At forty-five, not far removed from a mid-life crisis, what I need most is contact with a vital source. Surely, there are many paths to it, but mine leads through attempts to create the kind of myths that could move, stimulate empathy, and give hope.

I’m interested in fiction only if it’s a personal and, at the same time, highly universal, metaphorized and symbolic interpretation of the world and relationship with its elements, and not merely their realistic photography.

How do you feel about the translation of your work? Are there words and concepts you feel cannot be transmitted from one language/culture to another without losing something essential?

BN: It’s wonderful how thoughts can transcend the language they are expressed in. Depending on how distant the culture is, it can be a long journey or a risky trip to the unknown. Each of these perspectives is exciting because, during its adventures, the text meets the reader. They get to know each other, study one other, talk or remain silent; they are either fascinated with each other or, having exchanged but a few sentences, they part ways. Contact between the reader and the text is an encounter of two people and has all the features of such an encounter. I’m grateful I can share my way of experiencing the world with my readers. I think everything that relates to universal experience is translatable. Everyone in the world knows what love, sadness, loneliness, death, metaphysical experience, sensual pleasure or joy are, though in each culture they may be defined, experienced, inscribed in rituals, and visualized in various ways. I think difficulties in translation arise when you need to translate the description of something ‘endemic.’ I imagine, for example, that in some place on Earth there lives a tribe that feels an emotion completely unfelt in our culture or felt but nuanced enough that it is unnamed. Maybe somewhere there exists a color that has a name but is absent from the palette I know. How do you translate it when there is no word in this language to describe this color because it isn’t part of that world? My texts and poems have been translated into thirteen languages and I’ve had the great pleasure to meet each of the translators. Our conversations concerned not only the book – its idea, the world it depicts, the protagonist, plot, and language – but also literary and painting fascinations, didactic experiences, travel, culinary tastes, frustrations and passion. It was interesting and inspirational. During the translation process, Hendrik Lindepuu, an excellent Estonian translator, asked me what a “mouse tail with a ribbon” was. In Estonia, it’s not a phrase to describe a thin, woman’s braid. One of my texts features a personified Sunday. She is a mentally ill woman who wears a hat and a brooch, and she puts her hair in a thin braid. In French, Sunday is masculine. A he Sunday. Cécile Bocianowski, the French translator, and I discussed extensively what to do with this multiplied transgression. Conversations with translators are fascinating because they specialize in transferring things and phenomena to another world; they’re the pilots of the strangest expeditions, the sensuous smugglers of meanings.

And how have you engaged with Katarzyna in the translation process?

BN: The majority of my English translations and publications have appeared in the United States, thanks to Kasia Szuster. Three years ago Kasia sent several translated fragments of my poetic prose. I read the translations aloud. It struck me that in the English texts I heard the same rhythm as in the originals. Marek Bieńczyk, a notable Polish writer, describes a phrase as “a breath”; the breathing capacity of the author or narrator. In Kasia’s translations, I find my breath and the breath of my protagonist. There is some organic truth in it, the truth of the lungs: how many thoughts and images one breath can hold. I think Kasia has a brilliant sense of hearing and rhythm, which is after all, about timing. She uses these talents to measure human breath in another language. I appreciate that Kasia is in touch with live American English. Her husband, Mark Tardi, an American poet, interdisciplinary artist and educator, has lived in Poland for over a decade. Both of them are making efforts to publish my prose poems in the United States. They are talented, reliable, the salt of the Earth. I trust them and am happy to have Kasia translate my next stories and books. Another thing not without significance for me: when I met Kasia for the first time, after we had breakfast together, drank coffee and talked, I felt: she is a good, harmonious person, in touch with herself. I felt I could trust her. My intuition didn’t fail me.

Translators are the pilots of the strangest expeditions, the sensuous smugglers of meanings

In 2015, To Feed the Stone won Poland’s prestigious Nike Literary Award. Tell us how you came to the idea of To Feed the Stone? And why did you choose to present it as a prose poem?

BN: To Feed the Stone is a narrative that haunted me. I use this word fully aware of its meaning. I had to write this book. It was a necessity and a long, painful process, without which I couldn’t go on as a human. The volume consists of forty-four poems in prose. Each title is the name of an object. Its image is tied to a micro-story, which affects a human, and not a material, component. The central object in the story is the stone. The protagonist of the book, a girl a few years of age, tries to feed it and to do that, she’s looking for the right kind of food. The child believes she can feed the stone with her own senses: sight, hearing, touch and taste. That’s why she puts the stone in her mouth – the head seems to be the center of the senses. The child speaks to the stone, thinks at the stone, looks around on behalf of the stone. She wants to animate it and keep it to herself. The child–stone relationship – tragic due to its impossible nature – is the axis of the book. There are also threads related to complicated family life, emotional and physical violence, aging, death, illness, insanity, and sadness. It is a difficult book. But it has a silver lining. It comes from the child’s faith she can feed the stone. I wanted to create a metaphorical figure of an impossible but not entirely tragic relationship, because what is impossible, dramatic and upsetting in the child-stone relationship gets sublimated in the opening up of all senses to the world, in vulnerability laid bare because the child tries to feed the stone by means of senses. Everything the girl feels, sees, everything she touches and tastes is meant to nourish the stone. Keep it from dying. In fact, it also keeps the child from emotional death; a child who can’t find the emotions she needs in the living world and doesn’t receive enough love from adults. The story of the child and the stone wanted to be embodied in a matter different than the ones I had used before. It didn’t wish for me to photograph, stage, x-ray or film it. It wanted to be depicted in poetic language. Matching form to content isn’t dictated by the creator’s affiliation to a specific discipline, confirmed by a diploma or professional practice. I believe in the sacred ‘what’ which is preceded by the ‘how’: when the content is ready to emerge it finds a form itself. It does so somewhat beyond the creator, which it uses as a tool. The choices made by the ‘what’ are unforced, devoid of speculation, and natural; hence, I accept them as natural – without being taken aback. At the Lodz film school, my professors taught me one should not speculate about form until one knows everything about the content. They captured this principle, which is sacred to me, in a simple sentence: ‘WHAT before HOW.’ Once you follow it, the merit of this principle is that form manifests itself, in a way, as a reward for caring about the content. An authentic and cultivated ‘what’ naturally grows into shape. Before I started writing the ‘stone,’ I had watched it for a long time. I studied what it was, where it lay; what pain, malady or deficiency had bred it in me. When I was ready to make a text sample, the form presented itself. I also owe this form to my tendency for maximal synthesis and a certain reluctance to construct long, linear stories. It’s a matter of sensitivity, tendencies of perception, and dramatic preferences. I like stories built of pieces, shreds, micro-stories, and short scenes that comprise a portrayal, regardless of whether it’s built in the matter of language or image.

At LIT, we’re thrilled to have recently published your story Regnum. In it, we encounter four women – mad Mary, Ursula, insane Nina, and haunted Agnes – all of whom are in predicaments because of the fact they are women. And yet, as women they appear to possess secret powers and influence over objects and nature. Why did you feel impelled to write this story?

BN: I am also thrilled about this publication. Thank you for giving it a place in LIT. Regnum presents the stories of different women, whom some people call: a ‘nutcase,’ ‘crazy,’ ‘loony,’ ‘off’ or ‘strange.’ The story’s protagonists are highly sensitive. This feature may provoke people who lack empathy to abuse all sorts of things. Hence, the women in Regnum suffer abuse, passive and active forms of aggression, and experience exclusion and ridicule, also by loved ones. However, each of these women, thanks to their unique, heightened senses, experiences unusual contact with their internal life, their individual and collective unconsciousness, with the space of creation, symbols, the animal world, and other elements of nature. It’s a gift. However, they must ‘pay’ for it by ‘feeling too much,’ by being ‘hypersensitive,’ which is difficult to bear. I’ve created this narrative, first, because I have a natural weakness for freaks and sensitive people. I watch them with attention and respect. I look out for signs they send. Second, I have a debt to femininity – my own and in general. For over thirty years, I have been in touch with the world and people through the male side of my personality. I was guided by logic mainly, I didn’t have faith in my intuition, I was extremely task-oriented and demanding of myself and others. I gave up motherhood. My breakthrough experience at forty allowed me to pivot to my own femininity. This didn’t come without an internal struggle. The male part of my personality was convinced it was losing something: a dispassionate view of matters, impeccable discipline, the exclusive claim to be right. Once I tapped into my feminine element, I gained more empathy, I became more forgiving to others and myself. I began to have better contact with the subconscious, such as the sphere of dreams. I gained an appreciation for women. Their skills related to sensing emotions, conducting dialogue, seeking peaceful solution to conflict, readiness to help, multi-potency – “I’m stirring soup with one hand, and painting a picture with the other.” I owed Regnum to myself and other women. However, this story isn’t just about the feminine. It was spurred into existence by my desire to get closer to a life-giving source – a space that was spiritual, though unrelated to any religion, which in this story I refer to as the kingdom (‘regnum’ in Latin means ‘kingdom’). Recently, I’ve read a book by the Jungian psychotherapist, Marion Woodman. It was entitled, Conscious Femininity. Woodman writes about feminine nature, corporeality and power; in a compelling way, she explains what anima – the feminine element in a man – is and how it works. However, what I liked most about her book is how the psychoanalyst, who for many years had been working in in-depth psychology, talks about a woman’s attributes – care, maternal instincts, responsibility and safeguarding – as the only way to save the world, for example, from ecological disaster. It resonates with me. Not only because I’m a woman, but also because I care about the future of the Earth.

I believe in the sacred ‘what’ which is preceded by the ‘how’: when the content is ready to emerge it finds a form itself. It does so somewhat beyond the creator, which it uses as a tool.

Turning to your film work, such as Postmortale. Father and Postmortale. Mother, Aparat, and Ikona Regnum you’ve chosen to move away from conventional storytelling in favor of a more poetic, symbolic, at times almost clinical, narrative in which humans seem to play a secondary role, becoming archeological objects of a sort.

BN: Because your question is mainly about tomo-video works – films for which I obtained material using a computer tomograph (CT or x-ray) scanner – I will tell you why I employed this medium and why I’m attracted to clinical (I like your expression) narratives. While working on my doctoral thesis, I collected stories of relations between people and their things: sentimental, evoking the dead, recollected – they did not exist as matter but only as its image in memory; still alive, but condemned by their owners to annihilation. In this ‘research,’ which offered a canvas for my videos, I devoted special attention to the last category of objects. I tried to illustrate their path from matter to memory. Thanks to CT, I obtained graphic images of matter about to be destroyed. I x-rayed old suitcases, things left behind by the dead, the contents of boxes piling in basements or attics. I borrowed these things from their owners. With a CT, you can get not only static but also a moving image. The operations performed with the CT-scan reminded me of film staging: a close-up of an object, zoom, panning. Moving images reflect well the processes of transformation occurring in time, because they contain ‘time captured.’ It’s their component. Images in motion are suitable to express the remembered – film is one of the current metaphors of memory. This convinced me that the tomographic image is great for narrating something that changes, transforming from matter to memory. The original scan allowed me to obtain 3D reconstructions of each x-rayed object. These images not only testify to the appearance of things, but also to the veracity of their existence, confirmed through a medical device examination. They are a kind of ID for things. My clinical narratives are short documentaries. X-rays permeate matter. Their penetrative capabilities mean any image obtained with a CT can be delaminated. By removing the layers of an image, I was building associations related to memory: the degradation of memories, the process of forgetting. CT has a number of functions used to diagnose specific parts of the human body. Using these functions to shape images of inorganic matter produced a variety of poetics: ranging from hyperrealistic drawings to ephemeral ones, associated with the elusive, and by extension, the recalled. It helped me find a poetics fit for telling a narrative about the transition from material to recalled. The tomograph also allowed me to discover the traces of the past hidden in things. I took my old toy – a teddy bear – to the first tomographic session. X-rays showed the presence of sand in his ear. This sand could only come from two places – either my grandparents’ or my parents’ house yard. I thought: these houses are gone. And so are most of the people who lived there. Those sands are gone, but in the ear of my more than thirty-year-old teddy, there are still grains of one of them. Retrieving them is like turning back time. My teddy underwent a procedure by a professional surgeon. The doctor extracted clumps of dust from the teddy’s ear, a piece of wood shaving, probably from a crayon, and a dozen grains of sand. In this way, what existed only in memory regained material form. The film showing the “teddy surgery” became part of a gallery installation. The tomo-videos Postmortale. Father and Postmortale. Mother were based on scans of items left behind by the dead. The text accompanying the images refers to objects, but is designed so it can also metaphorically describe people, their characteristics, inclinations, weaknesses: mother – a birdcage, father – a doll collection, mother – a tailor’s mannequin, father – a silent radio, father – a closed box .

Where do you see your place within the world of European letters and art today? And how do you see your work addressing the issues of concern in Poland, Europe and the world?

BN: On March 12, the anthology Europe28 was published in England. This book consists of scientific and artistic statements of European women. They offer a vision of the continent’s future. It was an honor for me to participate in this project. The anthology featured my short story entitled “Void.” In the outline for the publishers, I wrote: “I want to write a story about the nature of a parable, where the construction of the characters and the plot is simplified in favor of symbolism and a moral message. As a humanist and artist, I believe that the basis for building European structures and social relationships should be empathy, communication, cooperation, creativity as well as a respectful attitude to remembering our ancestors and caring for those who will come after us. I am going to apply these values in my story.” I created a narrative about lessons: speech, looking, yearning, remembering, forgiveness, feeding, and enjoyment. These lessons are given to people by Master Craftsmen – mysterious beings. The workshop takes place in the conditions of the Void, when everything has disappeared: the landscapes, objects, relationship patterns, and even language. I do not condone the lack of empathy, the lack of respect for otherness and minorities. I deplore the lack of respect for animals, the Earth and pro-ecological activities. I’m terrified by xenophobia, myopia, a view of the world as if it were only a few square meters delineating the area of someone’s ideological trench. What can I do to express my disapproval? I can write. And give my support to people with open minds.

Can you share with us who your influences are, both early in life, in your career and now, Polish and world literature? And how have they influenced your writing and art?

BN: I think reading is one of the most sensual pleasures – I’m addicted to it. And I don’t want to be cured of this addiction. When I was a teenager, my relationship with books resembled falling in love. Dostoyevsky gave me genuine fevers. I found Kafka both alluring and disturbing. I was addicted to Hesse, Mann, Cortázar, and Márquez. Camus hypnotized me. Later, Joyce engulfed me whole. I was fascinated by Beckett. Enchanted by Pessoa. Moved by Márai. Amused by Michaux. Lima seduced me in a few minutes. Cioran attracted me intellectually. It was a frenzy that lasted for years. Then came Witkacy, Schulz, and Gombrowicz. Today, it’s a treat for me to read Herta Müller’s novels and collages or plays by Elfriede Jelinek, but I’m most drawn to literary borderlands, because that is where interesting hybrid genres and inspirational thoughts are born. One of my favorite authors, Piero Camporesi, a late philologist and cultural anthropologist, placed himself between literary studies and history, sociology and theology, psychology and dietetics, and in these unusual brackets, he created texts of world renown. The allure of Camporesi results from a clash between the documentary and the poetic, the factual and the unbridled imagery. Camporesi examines bygone bodies, studies the foods they were served and the rituals and repressions they underwent. Reading his Anatomy of the Senses, I discovered why butter and cheese were made from human milk and for what purposes these specialties were eaten; in which year a French midwife sewed the first delivery mannequin – an educational tool made of rags for women who were about to or had just given birth; and what the seventeenth-century backyard anatomical theaters looked like. I also read a lot of books in the fields of psychology, neuroscience, memory psychology, cultural anthropology, and psychophysics. I’m passionate about all types of histories: A History of Private Life, City: A Global History, History of the Body, Concepts of Cleanliness, History of the Body in the Middle Ages, Faces: A History of the Human Visage. I enjoy reading books by Draaisma, Ramachandran, Harari and Bergen. I’m also engrossed by Jung and Marie von Franz. My earliest and strongest reading fascinations set me in the poetics of magical realism, the later ones allowed me to appreciate the charm of departing from the classic narrative and psychology within it. My current readings correspond to my interdisciplinary interests. I think that the world of strictly defined fields, impermeable formulas, and tightly fenced areas of knowledge and art has come to an end. This is one of the reasons why I’m increasingly attracted to books written by cognitive international teams of scientists trying to find answers to questions about the roots of language, and the processes of remembering or creating meanings with our mind.

What are you currently working on and how do you see your work evolving in the future?

BN: I find a lot of joy in teaching. I teach at the National Higher School of Film, Television and Theatre in Lodz, where I have my own Inter-Faculty Workshop of Image and Word. I also have two other original classes. In the workshop, my students prepare film études based on contemporary Polish literature. These films go to The Creative Process international platform. My contact with students inspires me and mobilizes me to continue making an intellectual effort. I will definitely want to develop my classes and modify their program to strengthen their interdisciplinary character. I want the school to be my anchor, a place of inspiring meetings, and a litmus test of my intellectual condition. A new story has been brewing in me for some time. Regnum is its prelude. I think after the summer the book will be ready. One of the protagonists, my yuródivyy (holy fools) tries to create the world from scratch. Not because she can do it better than the original creator, whoever or whatever they might have been. She wants to see the point of existence of each thing and phenomenon anew: for example, the singing of a bird:

When forming a bird, remember that it is little more than adding a shell to the voice. Take the sound, coat it with flesh. Roll the flesh in down. A dandelion or poplar dust will do, snow not so much – it will produce a short-lived animal. Use horn for the beak. You can hew bones out of matches, if need be. Sew tightly the paired lung bag. Inflate it, slide it inside. Finally, put on some color, though it’s not necessary. Singing can soar in something as gray as wrapping paper.

Tell me, where are we now in space and time as this interview ends? (Again, this can be literal or imaginary).

BN: This is a time and space where gratitude can take the floor. Thank you, John, for giving me your time and an opportunity to reflect. Thank you, Kasia, for allowing me to share my thoughts and work with readers in the United States. I started with a kind of anxiety but the inner journey of seeking answers has soothed me.

***

Katarzyna Szuster

JPA: So tell us about the setting and place of this interview. Where are you as you answer these questions? (This can be literal or imaginary).

Katarzyna Szuster (KS): I’m sitting at a narrow desk in the sunroom. My laptop is on a pile of books, which is to simulate ergonomic working conditions (but fails), and my toddler’s toys are scattered all around.

Your first love was poetry. Can you tell us how you’ve come to be a translator of poetry and literary fiction? What are notable personal experiences that led you to become a translator?

KS: Ten years ago, my husband guest edited an issue of Aufgabe devoted to Miron Białoszewski and contemporary Polish poets. He invited me to work on it. At that point, I was a graduate student and hadn’t had much translation experience so it gave me chance to open myself to this trajectory. Another reason why I translate poetry is because on a daily basis, I translate all types of texts that are not particularly scintillating or potentially are, but to a very small group of experts.

What attracted you to Bronka’s work that you felt impelled to translate her poetry and stories into English?

The very first poem I read of Bronka’s was the opening to To Feed the Stone:

Sorrow teaches me that I’m used for living.

– When you’re eating – it says – your job is to remember to chew and swallow, that’s all. You see, your hair grows without your help, breathing and sleeping happens on its own, your eyes know how to close. Basically, you almost don’t need yourself for anything.

And it resonated with me – I loved the pivots, how the language seemed simple and effortless, yet the poem left you with things to ponder and feel.

Your translations of Bronka’s stories To Feed the Stone and Regnum are fluid and engaging, so that we have the impression they were actually written in English. What has been your creative approach and process to Bronka’s work? And how have you engaged with Bronka in the translation process?

KS: Very quickly, I realized that I could do a good poetry translation only if I genuinely liked the work and I could connect to it. To Feed the Stone is about objects that we all have at home and a child, who we all once were, and who some of us have at home. The book is a moving reminder of a child’s perspective; a child who is surrounded by unmagical things; things that are sad, ugly, serious or just ordinary. It is that lens of a child that breathes magic into them. I’ve used my two-year-old son to help me understand the book better, and the book to understand my child better. I don’t think I’ve ever contacted Bronka with questions in the translation process. It has never been unclear to me what she was trying to do. Some poems or parts may have been more challenging than others, but I’ve never really been puzzled by or unsure about the meaning of her work.

How do you view the craft/the art of translation, both literally and philosophically, within the wider realm of literature and the arts?

KS: I don’t think translation is much appreciated as art or even as activity. For example, the university system in Poland, which is strongly based on points these days, doesn’t credit points for translation while it does for other publications. Translators are often ghosts behind someone’s work midwifing it to a wider audience. Rarely are there translation celebrities. I speak generally, as Bronka’s has been appreciative of my work.

Translators are often ghosts behind someone’s work midwifing it to a wider audience.

As a translator, do you feel, as some have claimed, that translation is the ‘art of loss’ and that some words and concepts are untransmissible from one language/culture to another? How do you approach what seems to be lost in translation and untransmissible?

KS: I believe in a ‘good enough translation’, which I based on a concept from parenting, ‘a good enough mother’. Sometimes good is better than super (and surely, it’s better than bad). A poem especially has to read well, whether it’s in the source or target language. A translation that is too faithful and tries not to lose anything will seem contrived. So yes, you have to be able to lose some things gracefully and hope that the translation as a whole maintains the style and the feel that the original exudes. And perhaps along the way the translation gains some things too. I guess you can compare it to a song cover – it’s still the same song, but played in a different key.

As a woman translator, do you feel women bring something different to the craft/art of translation?

KS: I think that women definitely bring a lot to poetry, a certain lightness of touch. (I’m thinking partly of how Italo Calvino so astutely defines lightness in his lecture on the subject.) In translation, I only try not to lose it.

Can you share with us who your influences are, both early in life, in your career and now, within Polish and world literature and among writers and translators? And how have they influenced your writing and translation?

KS: One of the first poets I translated is Justyna Bargielska, a Polish female poet who definitely influenced my feel for translating poetry. My husband, Mark Tardi, who is also a poet, helped me realize that any piece of art has to make you feel something before you can engage with it. I would also mention the work of Miranda July, who is so wonderfully weird and talented, and, at the same time, honest and unsarcastic about human relationships that it gives me hope.

How do you see the role of translation within literature today in Poland, Europe and the world, and within larger issues of global concern?

KS: I hope that translation puts people from Central and Eastern Europe on the literary map (and not only a token person here or there) and helps break or challenge some stereotypes. Translation presumes that people in one place have some basic curiosity about cultures, people, and places different from their own, so I do worry that the surge of nationalism and xenophobia in various countries makes the work of translators (and translation) only more difficult.

What are you currently working on and how do you see your work evolving in the future?

KS: I’m finishing the manuscript of To Feed the Stone, which will be published by Dalkey Archive Press. My time to work on creative things is rather limited these days, but I would love to translate a book of fiction.

And finally, where are we in space and time as this interview ends? (Again, this can be literal or imaginary).

KS: I managed to translate one poem and finish this interview before my son is back from the nursery. It doesn’t seem like a lot but I see this as success. Dictionaries and diapers can go together, you just have to appreciate the quirks and scale back your ambitions to what is humanly attainable.

*** *** ***

BRONKA (BRONISŁAWA) NOWICKA is a Polish theatre and TV director, screenwriter, poet, and interdisciplinary artist. She is a graduate of the National Film School in Łódź, Poland, and the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts. Her literary debut, Nakarmić kamień (To Feed the Stone) was awarded the 2016 Nike Literary Award and the Złoty Środek Poezji (Golden Mean of Poetry) award. In 2017, she was a laureate of the New Voices from Europe project.

KATARZYNA SZUSTER is a translator. She earned her M.A. in English studies from the University of Łódź, Poland, and was a lecturer at the Department of Foreign Languages, University of Nizwa in Oman. She has translated various Polish poets into English, such as Miron Białoszewski, Justyna Bargielska, and Bronka Nowicka. Her translations have been published in Aufgabe, Free Over Blood, Moria, Biweekly, Words without Borders, diode, Toad Press, Berlin Quarterly, Seedings, Michigan Quarterly Review, and Tripwire.