Growing Up with a Low Rent Robin Williams

By Simon A. Smith

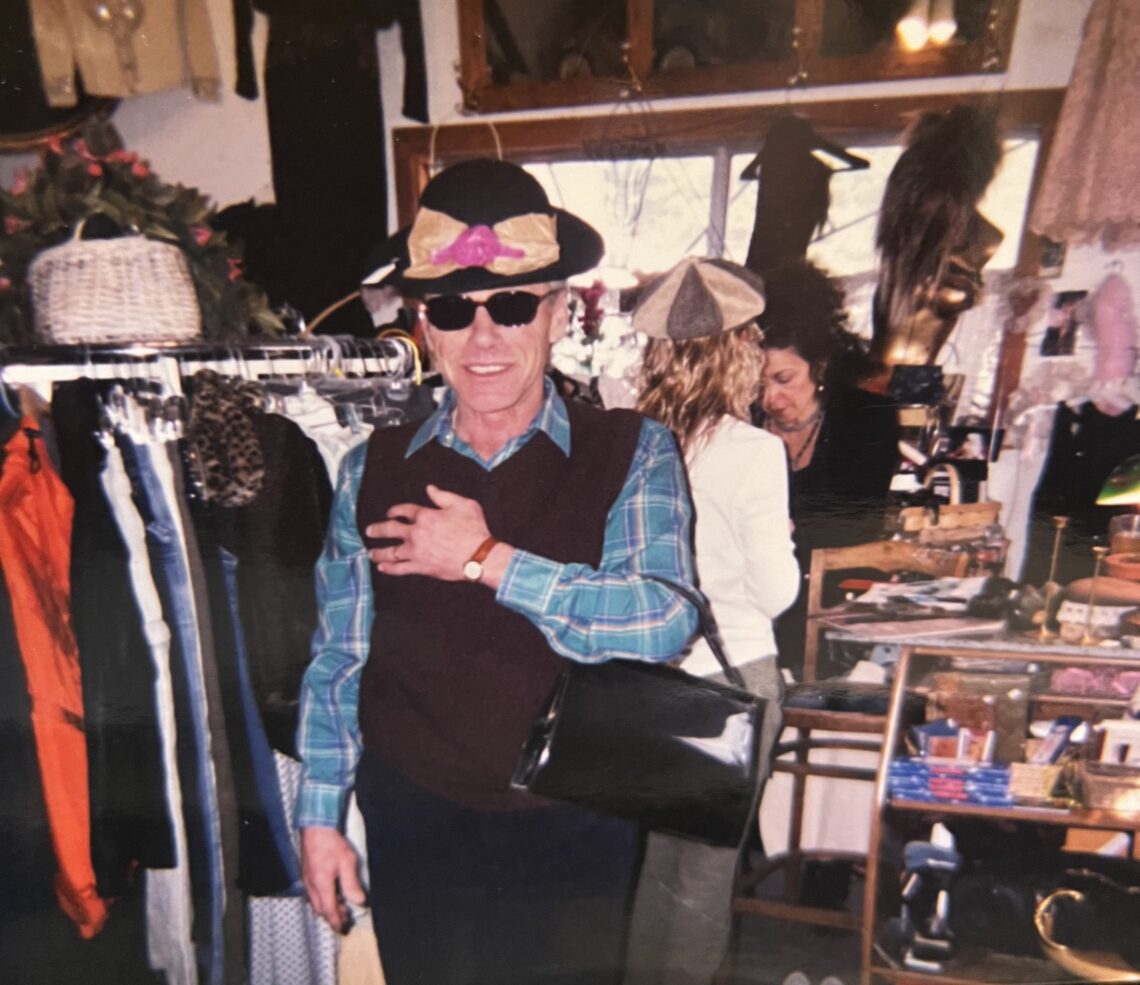

photo by the author

You never told anyone the whole story about your dad. You let most people think he was little more than a kooky horndog or dirty sailor. It was better for both of you. He got to see himself as the comedian he always wanted to be, and you got to pretend you weren’t dying inside every time he told another unsettling joke. That way, your friends felt it was harmless to laugh at all his unsavory antics. Like when you were at the pizza joint downtown, and your dad told your buddy that he’d like to hump the waitress. He laughed so hard that soda gushed from his nose.

Once, when your freshman crush came over to do English homework, she asked your dad if he could think of a single word that contained seven total syllables. The assignment was to write a haiku. You and your flame were at the kitchen table, sitting so close an envelope could have scarcely been slipped between your elbows, and your dad took that moment to come humming into the room, pull a beer out of the fridge, and announce, “I’ve got a compound word that might do the trick.”

“Oh, really?” she said. “Lay it on us.” She had this playful way with banter, half-biting and half-flirtatious, which drove you wild. It made things worse that your dad was a sucker for it too.

He gulped his beer. You watched him cycle through the word in his mind, counting and recounting the syllables on his fingers. When the calculations ended, he nodded and smiled. “You ready for this?” he asked.

“Hit us with it,” your crush said.

He lingered, drawing out the suspense, then let you have it. “Je-sus-mo-ther-fu-cking-christ,” he intoned.

Nobody moved at first. You closed your eyes because you couldn’t look at your dad, and you definitely couldn’t look at your crush, and because you still had that childish belief deep inside that if you couldn’t see anybody then nobody could see you either. And when you felt her arm slide from the table, you were not surprised that she was pulling away. You were not surprised that she’d decided to pack her things, leave your house, and never return. What you were shocked to discover, when you opened one eye, was that your crush had only removed her hand so that she could raise it and place it over her quivering mouth. You were shocked to find that she was now lost in convulsions, great gusts of laughter you worried might topple her from the chair.

Your dad shrugged and left you there, alone with your gasping dream girl, wishing she’d never asked him a question, yearning to rewind time and go to her house instead, or maybe be born to a different father who wasn’t some screwball prone to deranged outbursts.

After she calmed down, after she dried her tears, and took several deep breaths, she put her fingers on your bare wrist. Waves of nausea churned in your gut. “Man, your dad is something else,” she said. She looked you straight in the eyes and said, “I wish I had a dad like yours.”

**

He’d gotten out of jail only a few months earlier. His road in was paved with a different kind of indignity. For years he’d driven drunk, PBR wedged between his thighs, careening down backstreets with you riding shotgun, struggling to endure the cigarette hotbox that was his 1985 Datson. You were his little crony, his plus-one at all the dive bars, places where he gave you quarters to play shuffleboard, ordered you fried chicken, and let you drink Pepsi while he sat at the bar and told crass jokes about homosexuals and potheads. It wasn’t that he disapproved of the lifestyles, only that he considered laughter so much more important than dullness or decorum. On the way out, he’d ruffle your hair, ask you not to tell mom when you got home.

Mom already knew. You didn’t have to say a word. Between his slurs and stumbles, he was his own worst secret-keeper, a walking confession before he even hit the living room. The confrontation went the same every time. Mom fixed him with her infamous glare, the narrowed eyes and chiseled lips, and Dad responded with mock consternation.

“What?” he’d say, throwing up his arms. “What is it now?”

You’d go to your room and play video games or maybe go outside and shoot basketball with your next-door neighbor, Kevin. You’d try to take your mind off how lousy things were, how despite the mounting aggravation from his wife and law enforcement, your dad’s drinking was only getting worse. It was so bad that Officer Shifflet snatched his driver’s license, and when he didn’t quit, Shifflet added two years to the suspension and fined him 5,000 dollars. And because your mom knew that he was still picking you up from school and soccer practice, she took the type of action that only a desperate mom would. She called the cops herself and told your dad’s secrets.

On the day the police came to arrest your dad, you were the only one home. The bus had just dropped you off, and you were probably watching cartoons, doing what every thirteen-year-old did to unwind after school. But if you were a normal kid, you wouldn’t have a dad who came bursting through the door, shouting for you to flee the scene.

“Hey! It’s me. Get out. Go! They’ll be here soon!”

You leapt up from the sofa, zero-to-sixty in record time. “What? Dad! What’s going on?”

“The cops. They’re after me. I didn’t do anything, okay. I didn’t do anything!” he repeated.

That’s when you looked out the window and noticed your dad had parked his car in a very odd location. Instead of pulling it up to the garage like he usually did, he tried hiding it far back in a wooded area at the edge of your property. It wasn’t even really hidden, just… out of place. If he’d had the chance, you thought, he’d likely have covered it with leaves for heavier camouflage or something. The whole thing was so conspicuous, and you know that if you could see it, the cops would see it too. You wanted to help, but there was no time.

“Don’t tell them I’m here,” he said. “I’m not here, okay?” His voice was shrill and teetering on the edge of breakdown. He was on the verge of crying, and because you’d never heard him cry before, and because he was your father and protector, you started to cry also. “Don’t cry,” he told you, even though you were pretty sure he already was, and then he opened the door to the attic, slammed it shut, and dashed upstairs.

You stood there and tried not to weep. Tears rolled down your cheeks. Your knees wobbled, and your heart raced. The Captain Planet theme song played in the background. There was no way you could run.

Moments later, you watched a police car come rushing up your driveway. Two officers stepped out and made their way straight to your front door. You’d never seen either of them before, which was even scarier, because at least you knew Officer Shifflet, at least he’d been to some of your baseball games and was the husband of your gym teacher, Mrs. Shifflet. They knocked hard, and rang the doorbell, then knocked and rang again. It went on like this for a while, until you were unable to resist any longer, until you felt as though you might pass out or pee your pants if you had to hold them off for one more second. You wondered if they could arrest you too, so you opened the door. They came at you full throttle.

“Where’s your dad, son?” the man asked. There was one male and one female officer. “We saw his car already,” he said. “We need to come in and look around. Son? Son, you need to let us in, and do what we say. Do you understand what he’s done? Do you know what’s happening –”

The female cop intervened. She put her hand on the man’s chest and spoke over him. “Hey, buddy. Listen. It’s okay. We aren’t going to hurt you or your dad. Can you please let us in? Do you know where your dad is?”

You couldn’t speak, but you could move your head. You shook your head no, but you also let them in, so it was impossible to tell what your headshake actually meant. It didn’t matter because they were inside now. They were spreading out, calling your dad’s name. They had their hands on their holsters, but they were not raising their guns. The man located the door to the attic. He put his palm on the doorknob and turned to you. He addressed you and his partner in tandem.

“Is this a door that leads to a basement or attic?” he asked. “Am I going to find him in here?”

Because you were simultaneously covering for your dad and trying to avoid a horrendous disaster, and because you were more frightened than you’d ever been in your entire life, you shook your head and nodded at the same time. Because you loved your dad, and because you were also dying to make the nightmare end, you let them open the door and slowly walk up the stairs. You knew they’d found him when you heard your dad wail. You heard him make the most excruciating sound, like a dog that had been kicked hard in the ribs. It was the saddest noise you could ever imagine anyone making.

**

The strange thing was that you’d seen pictures and heard stories about your dad when he was growing up. One thing that was easy to tell was that he came from a very religious family. If the bible verse needlepoints in Grandma’s kitchen didn’t give it away, the Billy Graham radio program playing in Grandpa’s sitting-room would. Getting more information was hard, especially when you were younger. According to your Uncle Les, when he was in high school, your dad was shy and reserved, the type of kid who would go out of his way to avoid attention. If he was called on in class, he responded so quietly that the teacher had to yell at him to speak up. In his senior picture he looks handsome with his square jaw and razor-sharp crewcut. In his twenties, people told him he looked like Charlton Heston. If you’d only heard stories from your three uncles, you’d have an impossible time trying to piece things together. How did this God-fearing, clean-cut boy with movie star looks, turn into the loony father you knew?

For better or worse, you also had aunts, three ladies who were a lot more candid than the men. They were more willing to talk about the darker sides of their childhood, and the older you got, the more open they became about the sinister parts. Your aunt Susan in particular, a self-proclaimed “basket case” and the only sheep blacker than your dad, told you about your grandfather’s rabid temper. When your dad was about twelve or thirteen, Susan told you, Grandpa beat him so badly that he needed to be rushed to the hospital. Before that, she said, he would rough your dad up, come into his room at night in a psychotic rage and punch him and his brothers in the head for some reason that only made sense to his own schizophrenic mind, but there were times when he went way too far. Schizophrenia ran in your family, she said. She bet you didn’t know that, but it was true. The two of you sat there for a long time after, silently lamenting, and when you hugged afterward, things made a little more sense.

It made a little more sense now that your dad had turned to alcohol to medicate all the trauma he’d experienced as a child. You had a little more insight into how he became the man who got drunk every night after work, took steaming baths after dinner, and then wandered around your backyard in a bathrobe, muttering to himself as he scooped birdseed into the dozens of feeders he’d strung up all over your property. All the mortification you used to feel as you thought about the neighbors who might see him out there, babbling in his manic stupor, buck naked under the robe, it started to lose some of the anger that used to surround it and was replaced with a larger dose of sorrow.

**

When you were in Little League, your dad was still your hero. When you told him you wanted to be a catcher, he carved you a home plate to squat behind and a pitching mound for him to perch atop. He was a hell of a carpenter. Everyone said so. In fact, concocting baseball apparatus was about the lowest form of construction he did. He built your entire house with his bare hands, no matter how inebriated he was during the process. It was the same resolve he used during your pitching sessions as a boy. You practiced for hours on the weekends. Say what you will, but he made time. Every Saturday there he was, Winston pinched between his lips, whipping fastballs in the dirt or airmailing cutters over your head just to test your reflexes. He was almost as good of an athlete as he was a craftsman, snockered or not.

The following spring, despite your dad’s efforts, you weren’t the starting catcher. In your defense, your team was stacked. It seemed like every season your team, The Warriors, won the county championship. Half the players made the All-Star squad every year. That wasn’t the point, your dad said. He said that the point of playing Little League baseball was to have fun. The coaches took things way too seriously. He wasn’t wrong. The year before, Coach Hubbard slugged a fan on the opposing bleachers because his raucous whistling was annoying the crap out of him. Your dad said your coaches were a bunch of lame brains, and you couldn’t really argue. You went along with whatever he said, until the day you couldn’t anymore.

It was following the last regular game of the year. Everyone was circled up under the big oak tree beside the field, listening to Coach Hubbard prattle on about preparing for the playoffs. He started in on some of his favorite topics, “manning up,” “putting away your skirts,” and “pulling on your big boy pants.” It must have been ninety degrees, and everyone was sopping with sweat, especially the catcher, Andy, who was completely cooked, pink as a boiled ham and soaked to the bone.

Hubbard kept yapping, and then all of a sudden he trailed off. There were footsteps creeping up behind you. Coach stopped talking and everyone turned around. There was your dad in his corduroy pants, his button-down shirt, and leather sandals. Your dad was often overdressed for occasions but none more than this one. He was short and wiry, but on this day his shadow loomed over all of you like a behemoth twice his size.

“Hey, Coach,” Dad said.

“Hey there, Mr. Smith. What’s up?” Coach asked.

“Have you gotten to the part yet where you tell the kids that the most important thing about Little League baseball is having a good time?”

“That’s nice,” Coach chuckled. “Sure, I like that. But winning is even better. These boys are trying to bring home a trophy.”

Your dad laughed. He folded his arms over his chest and grinned. “I see. So, then you’ll finally be able to quit your day job and go on The Johnny Carson show with all your fame?”

“That’s funny,” Coach said. “I don’t need Johnny Carson to tell me I’m right about this.”

“They’re eleven years old, Hubbard,” Dad said.

“It’s never too young to build a winning mindset.” Hubbard took a step toward your dad, so that their pelvises were almost touching, but Hubbard’s head was a good five inches higher.

“You’re ridiculous,” Dad said. He considered stepping closer himself, giving him a little crotch bump, but thought better of it. “I guess you don’t get it.”

“Nice talking to you,” Coach scoffed.

Your dad turned to leave, but right as he did, he got in one last comment. “Well, fuck you very much,” he said, tipping an imaginary hat.

Hubbard returned to you and the rest of your team under the tree. He looked right at you and shook his head. “Jesus,” he sighed. “Well, like I was saying, it’s time to lock in, boys.” For the rest of the lecture, everyone stared at you instead of Coach. You looked at the ground. You picked blades of grass and tried not to scream.

Afterward, in the car, Dad asked you if everything was okay, even though he knew it wasn’t.

“Why do you have to do that? Why can’t you just leave things alone?”

“I’m a poker, I guess,” Dad said. “I like to poke big old dopey bears.”

“Nobody else does that. You’re the only one!” you said. You cranked the window down so hard you hurt your wrist.

“Robin Williams does shit like that all the time, and people eat it up.”

“Who is Robin Williams?” you asked.

“He’s a comedian. He’s hilarious.”

“You are definitely not Robin Williams,” you said.

You sat there for a while in the heat. You could tell he didn’t know what to do. “He should put you in,” he said. “You’re better than pig-faced Andy.”

You shrugged. He was hurt, and you felt bad, but neither one of you was good at saying what you were feeling, so he just started the car, and the two of you drove away in silence, trying not to think too hard about the damage you’d both caused.

**

While your dad was in jail, you did everything you could to keep his incarceration under wraps. When your buddy Nick asked why he wasn’t coming to any of the basketball games anymore, you told him that your dad was fishing in Raystown Lake, and a few weeks later when he asked again, you said he’d gone on a hunting trip with some friends. Your neighbors started getting curious. Kevin’s dad, Albert, came outside one day while you were mowing the lawn and asked where your dad had been all summer. You told him that he was working as a foreman on a new housing development up in Lackawanna. Albert looked at you like he knew you were lying, but he didn’t want to upset you. He nodded and patted you on the back.

“If you need any help around here, you let me know,” he said. “I’m just a house away.”

“Thanks, Al,” you said, “but he should be home soon.”

That night you told your mom what you’d been doing, weaving tales all over town. She was somber in her response but also resolute. She didn’t want to back down from the decisions she’d made.

“I’ve been telling people that he’s visiting a long-lost aunt in Millcreek,” she said.

The two of you sat there at the kitchen table for a little while, feeling sorry for yourselves and then suddenly it hit you how comical it all was, making up stories about all the ridiculous journeys your dad was supposed to have taken but had no knowledge of. You started laughing, and then your mom caught the bug too. You both laughed for a long time, until your eyes and noses started running, and you went through wads of Kleenex. Then you put on your dad’s oversized sandals, grabbed his bag of birdseed from the garage, and walked around filling all his goddamn bird feeders. Outside, the night was serene and starry. Dry grass crunched softly beneath your feet. The world was fresh and freeing at this hour, receptive to your every whim, and by the end of the task, you finally understood your dad’s attraction to these evening rounds.

**

During his final days, when your dad was sick and wasting away, you went to visit him at his small house in the mountains. He’d moved 2,000 miles west to escape all the people in his life who thought he was too delusional to deal with. In Grass Valley, there were no Coach Hubbards, or ex-wives, or even sons to tell him that he was off his rocker or causing too much pain. Maybe he thought that if he could outrun the lame brains he could outrun throat cancer, but it was no use. The most heartbreaking thing was that if he had managed to arrive in California five years earlier when he was still healthy enough to sit on a back porch, drink rum, smoke weed, and listen to classical music, he would have been in heaven. Grass Valley was the perfect place for your dad. Plenty of birds, solitary walks, and lots of artsy residents who looked upon his mental illness as more of a daffy eccentricity.

Instead, what you found was a frail man who could hardly breathe. A man who spent most of his days sky high on morphine. The whole time you were there he kept trying and failing to give you a tour of his house. He didn’t have the lung capacity, so most of what you did was help him back into bed and watch him drift in and out of sleep.

“I should probably get going,” you said.

“Huh?” he said, coming to, bolting upright. “No, no!” he said. “First,” he said, “you have to throw baseball with me. I promised myself we’d throw baseball one more time. I have my glove,” he said, and then he reached under the covers and pulled out a baseball glove that you hadn’t seen in twenty years. It was moldy around the hand opening and rotted at the tips. It looked like something a rottweiler had been using as a chew toy for decades. Inside the glove there was a baseball, and somewhere inside that baseball were all the memories of every time you’d ever played catch with your dad. It took all your might not to break down and start sobbing right then and there.

You watched him wiggle his bony fingers into the glove, watched his lids flutter and his arm twitch with every movement, and you knew that there was no possible way he’d be able to toss the ball more than six inches.

You put your hand on his shoulder and squeezed. “Dad,” you said, “it’s okay. We don’t have to do that. I appreciate it, but…”

“Oh, come on, fucker!” he shouted. He reared back with whatever strength he had left in his entire body and socked you on the arm as hard as he could. It hurt a lot, and you were glad it did. He wasn’t dead yet, and he needed to feel something real one last time. He started coughing, and his face turned red and swollen. He sighed and swayed back against his pillow.

“It’s okay,” you said again, and now you were really going to bawl. If you didn’t get out of there soon the floodgates would open, and you’d really be in trouble. “We don’t have to throw now because I remember,” you said. “I remember all the times we ever threw baseball, and… and, I will never forget.”

He was already half asleep again. His battery was drained. It had been a tough day. He let the glove fall from his hand and closed his eyes. “Alright,” he whispered, “okay then.”

And then you took the biggest, deepest breath you’d ever taken. You kissed him on the forehead and you left.

**

On the day your dad came home from jail, you could tell his first priority was getting things back to normal as fast as possible. He spent the morning organizing paperwork, and then preparing his coffeepot, lunchbox, and tool bag for work the next day. During the afternoon he sat at his workbench in the garage, listening to Tchaikovsky on his small radio and super-gluing knickknacks back together that had broken while he was gone. Before the sun went down, he got his wheelbarrow out, filled it with a shovel, a rake, a couple beers, and some Quikrete, and headed down to the bottom of your driveway. There had been some heavy rain the previous week, and the water had washed a bunch of stones out onto the street. You watched him wheel the things down from your bedroom window. You wanted to help him fix the driveway. You wanted to talk to him and just be near him, but you didn’t know what to say. You didn’t know how to be close to him and also get close to him, and the prospect of just standing next to him and sifting concrete in a bucket while no one said a word seemed gut-wrenching in so many different ways. But you decided to go help him anyway.

When you were about halfway down the driveway, you noticed that Kevin had gotten there first. You guessed he’d been outside already, maybe shooting basketball, and he had seen your dad working. Kevin, being who he was, a smalltown kid who had been raised to help an elder carrying shovels and rakes, jumped right in. You quickened your pace, and as you got closer you could hear their conversation.

“So, how was it then,” Kevin asked. “All your hunting and fishing trips?”

“What?” Your dad said. He set the bag of Quikrete down and looked up at him from where he kneeled. “What the hell are you talking about?”

You tried to move faster, but you knew it was too late. You couldn’t just shout something to drown out their conversation. What would you even say? How could you possibly explain what you’d done over the last six months? You couldn’t just holler, Wait, Dad! I’ve been telling absurd lies in a pathetic attempt to save your reputation and preserve my own pitiful existence! There was nothing to be done, so you just stayed where you were, paralyzed with humiliation.

“I thought you were off living it up with your boys. I wished you’d taken me and Simon with you,” Kevin said.

“Shit, I wasn’t on any trips with my boys,” your dad said. He laughed hard. Some of the chalky dust from the sack had gotten on his face and hair. “I was in jail!”

You and Kevin were both done for then. You, frozen in the driveway, Kevin paused in mid-thought, leaning on the shovel.

“What?” Kevin said, and he was sort of laughing too, but in a much more nervous way.

“I mean, it may have felt like vacation from time to time, to be honest. It wasn’t as bad as people say it is.” He stood and clapped the soot off his hands. He picked up his bottle of Pabst Blue Ribbon. He held it aloft like he wanted to toast Kevin, but Kevin didn’t have any beverages. “As I always say,” he said, smirking, “if it wasn’t for the grace of God, I’d be sipping a pina colada on the beaches of Jamaica right now.”

And just like that, he was back. The typical dad moves were still intact. Kevin reacted the way everybody did who didn’t understand the role your dad was playing, the charade that only he could envision in his tragic mind. He chuckled for a second, then stopped abruptly. He looked closer at your dad’s face to see if he was joking or not, but he couldn’t tell. Nobody ever could, and that was part of the reason he ended up so alone and ravaged in California, but it was far from the only reason. It was nobody else’s fault. You don’t know how many hours of your life you lost pleading with him to see a therapist, or join a group, but he never listened. Humor, alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana were his self-proclaimed remedy. And for a long time, it made you so angry. It made you angry enough to almost hate him. In the end, for Christ’s sake, in the end, he did turn out like the real Robin Williams. Two tortured souls, performing away their buried suffering until they couldn’t conceal it any longer.

Goddammit. And as much time as you’ve spent agonizing over how much you wish he had been different, how much you longed for him to be ordinary and sane like everyone else’s dads seemed to be, the only thing in the world you want to do now is return to the bottom of that driveway. You want to go back in time to that very moment. If only you could walk the rest of the way down that driveway and wrap your arms around his scrawny body, you would give him the biggest hug. You would never let go. No matter how much he cursed and cackled and said the weirdest shit anybody had ever heard, you would not let go.

Simon A. Smith is a Chicago teacher and writer. His stories have appeared in many journals and media outlets, including Hobart, Whiskey Island, Chicago Public Radio, and NewCity. He is the author of two novels, Son of Soothsayer, and Wellton County Hunters. He lives in Rogers Park with his wife and son. You can find more of his work at https://www.simonasmith.com/.