In the Old Capital

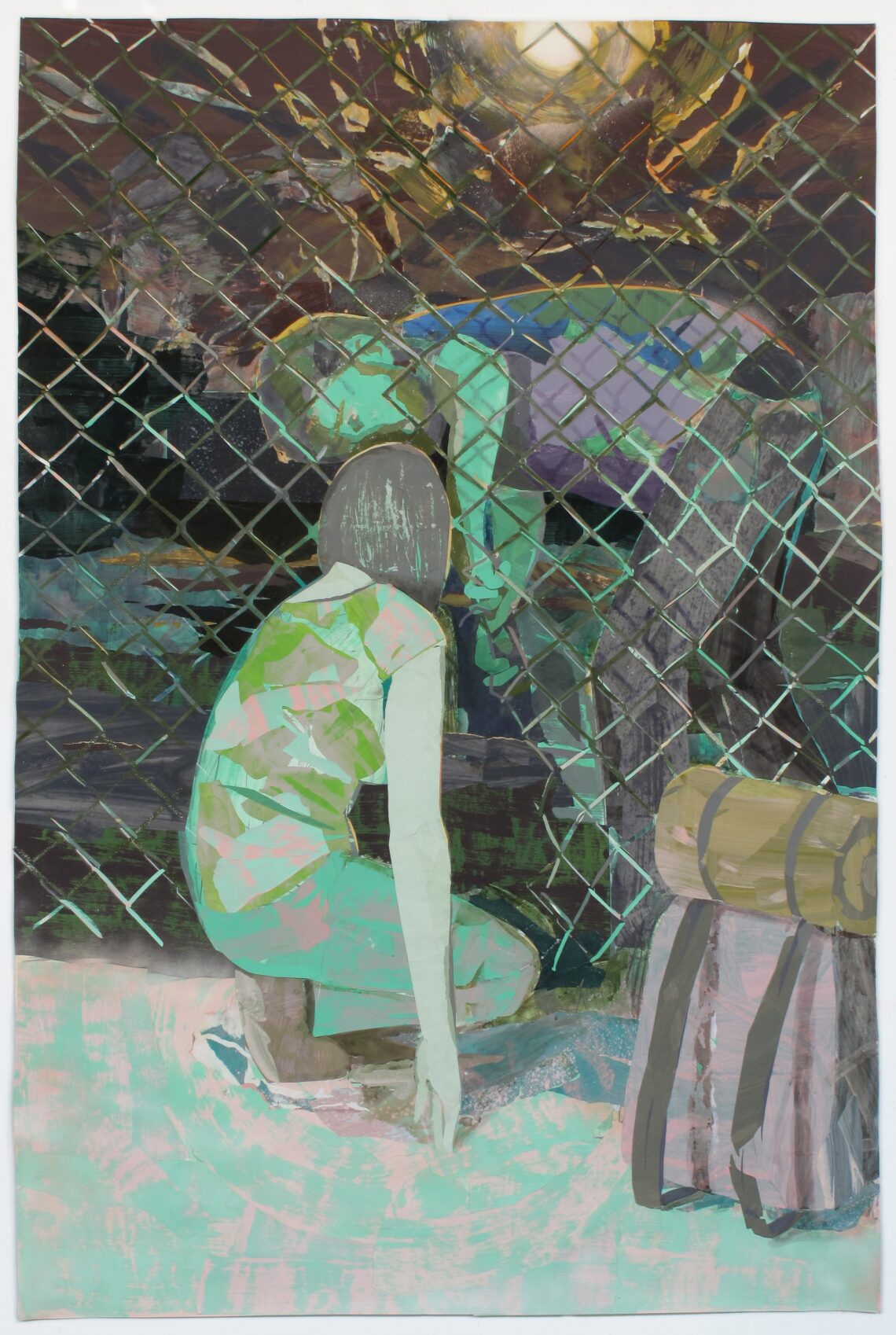

Art by Matt Bollinger

by Yuko Iida Frost

One night after work in December, I decided to hop on the express train to visit Masa unannounced. The restaurant where he worked was tucked behind a quiet street, off the Imperial Palace. The oldest in Kyoto, it used to serve the emperor until the capital moved to Tokyo, formerly called Edo, in the late nineteenth century. The street was dark. Their unassuming façade disguised its legendary reputation and looked more like an entrance to an old merchant’s house trying to hide his wealth. The sliding door was almost invisible with only two dimly lit paper lanterns hanging on both sides. The kitchen was hidden behind the tall weathered wooden walls, almost invisible from outside, but if I stood close to the wall and stretched my neck, I could see inside. I might have looked like a burglar casing the property, or a woman spying on her unfaithful lover, but luckily no one was around. I settled myself in that position and watched the world of imperial cooking unfold in the nearly three-century-old kitchen.

Masa and his fellow apprentice and chefs all in the long white starched aprons seemed laser focused at their assigned positions. Middle-aged waitresses in graceful purple silk kimonos came and went carrying black lacquer trays. The steam from a large pot of boiling water made the windowpanes cloudy, but I could still see them hustle. One cook was slicing a block of raw tuna into thin pieces. Another poured kelp and fish broth into black lacquer bowls with gold chrysanthemums, the imperial crest, painted on the lining. The sound of traditional shamisen guitar floated out. I studied Masa’s face, wondering how I should surprise him. He moved his long torso from the front to the side rhythmically, placing finely curved root vegetables, that were made to resemble lotus flower petals, onto the porcelain plates. He was sweating slightly on his forehead. I had never seen him so spirited.

The last time Masa and I were together in his apartment, he’d talked about moving to Tokyo, to be near his family in Sendai, a large city by the scenic port in the north, where he was born and grew up. “I could open my own restaurant someday.”

“What about us?” I asked.

“You’ll join me, of course. Won’t you?” A dark shadow ran across his face.

“What do I do in Tokyo?”

Looking incredulous, he said, “You’ll be with me. Isn’t that what you want?”

Was that what I wanted? I still hoped to go to a university someday somewhere.

A few years earlier, as a high school senior I failed my initial university entrance exam. Instead of encouraging me to try it again, my father said I didn’t deserve education. “Girls don’t need to be educated anyway,” he slurred, putting down his sake bottle on the table like a judge pounding a gavel. Years before, he had promised not to stand in my way so I could realize my dream, whatever it might be, as his own father had done. What happened to that promise? The alcohol must have erased his memory. My dream shattered, I promised to myself to work hard, save money, and find a way to educate myself.

Shortly after I landed on my first full-time job at Daido Life Insurance, I reached out to my former high school teacher and asked how I might be able to earn a university degree while working. He wrote back explaining different options including correspondence school and night courses both of which would take years to complete. His letter ended with this question: “Why bother with a university education? A university degree usually won’t further a woman’s career. Besides, women quit working once they get married and have a child, right?”

I began to explore the idea of studying elsewhere, perhaps in the United States. Then I met Masa.

“The beginning is most important,” Chizuyo had said to me when I told her about my first date with Masa. My then eighteen-year-old friend at work and I were in the women’s locker room changing into our company uniform.

“You must tell him what you want, how you’d like to be treated, and what you don’t like at the very beginning so he will learn and remember. Don’t wait till it’s too late.”

I was young, too, and didn’t pay attention to her warning. I should have.

In the dark street outside the restaurant, a snowflake perched on my face and made me shiver. It began to accumulate on my shoulders but I wanted to keep watching him from the darkness. The world inside—the traditional art of Japanese cuisine, the sound of shamisen music and silk kimonos rustling, paper shoji screens, and old black wooden lacquered bowls–was not where I belonged. It looked like a scene from the tenth century Heian period.

Earlier that month of December, I had performed a soprano part of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with a professional orchestra and soloists at Osaka Symphony Hall. I was one of the hundreds of the amateur singers who had passed the audition to join the choir. We practiced in German every night for three months. On the day of the performance, I stood on the highest stand as a soprano, facing the large audience under the blinding lights, I was Maria Callas, screaming from my diaphragm the highest, the most climactic notes of the entire German score. Among the audience was my mother, her sister, Chizuyo, and a few other friends, and my colleagues. Masa was not there.

I was beginning to tremble in the wet snow. It was then I heard the music in my head. It wasn’t the shamisen’s sinuous tune. It was Beethoven’s choral music and it warmed me. The sudden wind made me step back onto the alley now covered with the white flakes. I pulled out a handkerchief to wipe the snow off my face, and began to retrace my footsteps to the bus station. The cold wind intensified, hitting me hard as if to push me back into the darkness. I steadied myself and reached the main street that was much brighter with street lights. I began humming Beethoven, thinking of the stage under the blinding lights, and hearing more voices singing the familiar song.

In the new year, Masa called to tell me he was in Tokyo and that he would not be coming back. He was about to land a new job. He would arrange a train ticket for me to visit Yokohama to meet his sister and her husband. He would join me there. From there, two of us would take a north-bound train to Sendai and meet his parents. That was his plan. He called a few more times but did not leave a phone number where I could call back. He called less frequently. Four months passed without hearing from Masa.

During those four months, I did things I hadn’t done before. Chizuyo and I traveled to a small inn with a hot spring and enjoyed our girls time. I read more books—my favorite became The Soul Enchanted written by Romain Rolland about a young woman who decided not to marry her fiancé when he turned out to be far more conservative and controlling than she had realized. I registered with a modeling agency and began working part time as a model. I also began taking classes at an English language school which provided not just language lessons but also helped young people prepare for studying abroad. I was moving a step closer to my dream.

One late afternoon Masa finally called me at my office. “Oi, I’m back.” His voice sounded tired, like an old fisherman who just returned from a rough sea.

“Where are you?” I whispered covering the receiver with one hand trying to be discreet in the open office.

He said he was staying with his old master in Kyoto. “Can I see you tonight? I’ll take a train to Osaka.” His voice had never sounded so accommodating.

“You disappeared for months, and you want to see me now?”

“I cut myself badly last week. Had to go to an ER.”

“I’m sorry,” I said and recognized the pattern. He evaded my question and kept our conversation only about himself.

“Meet me at Osaka Station at six-thirty.”

Chizuyo saw me, looking concerned. I got up from my desk, and left the room, pretending to go to the bathroom. Chizuyo followed me to the locker room.

“What happened?” She closed the door behind us.

“Masa’s coming to see me tonight.”

She squealed, raising her both arms. “He surrenders!”

I did not feel as victorious as she thought I should.

“Why are you so upset?” she asked.

“I don’t know. Part of me still wants to see him. We might be able to work things out, but I doubt it. I need to have a serious talk with him and he won’t like it.”

“Maybe that’s why he’s coming to you.”

It was a warm spring night. I wished for a storm so it would sweep away all the car exhaust and muddy clouds hanging above our city. It might also clear my head. Masa was leaning against a wall, wearing blue jeans and black leather jacket, hands in his pockets. He saw me and pulled both hands out, straightened his posture, and waved his left hand, wrapped in white bandage. It did look like he was holding a white flag. His face was thin, eyes sunken, and his skin lost its luster.

“It’s been a long time,” he said.

“Four months.”

The train station made a loud announcement. He suggested we go to a quieter place and held my arm with his uninjured hand.

“What’s your plan now?” I asked.

“I’m back in Kyoto only for one day. I’m leaving tomorrow for Sendai.”

“What happened in Tokyo?”

“It didn’t work out. I’m going to get a job near my family. I want you to join me.”

I didn’t respond. He lowered his eyes as if searching for any trace of disagreement.

“Did you miss me?” he asked.

“What do you think?”

“I don’t know. You seem so aloof.”

“You never gave me your phone number.”

“I didn’t know what I was doing. But you seem more certain. What’s on your mind lately?”

I told him all what I’d been doing. “I love my part-time modeling job. It pays me more than what I make with a full-time job. I’m saving it all for my education.”

“Why modeling? I can’t imagine you doing that. You’ve already got a job.”

I told him about the French Collection at Osaka Festival Hall, the stage I walked in the famous designers’ clothes like Kenzo’s elegant long dress. It was the same place where I’d sung Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. “I loved it.”

“I’m not sure that’s for you. Modeling sounds so dangerous.”

“How is it dangerous?”

He looked grumpy. We came to the narrow street where numerous restaurants, bars, cafes, and pachinko parlors competed for space. Masa lowered his voice and said, “See that woman over there?” He pointed with his chin at a demure looking young worker in a white apron sweeping the sidewalk with a broom in front of a sushi restaurant. Her hair was tied in the back of her head in a bun. Her slender body was bent forward as she swept away from the door, occasionally stopping to let a group of customers come into the restaurant, greeting them politely. “That’s what you’ll be doing once we open our restaurant,” he said nonchalantly. “That’ll be you someday.”

Suddenly I remembered all our time together like watching a flash forwarding film, our first kiss on Kiyomizu, our first love making, holding hands as we walked in Kinkakuji, watching him work in the kitchen through the narrow window, many moments of embrace. And all this time, he was thinking of his dream only.

The woman was already behind us, but her image was burned inside me. Her sweeping movement, her bamboo broom pushing the dirt out of the entryway, bowing to the customers. Her youthful face looked tragic. I had once adored Masa, dreamed of being married to him, imagined our utopia somewhere far away.

“Are you listening?” He stopped. I looked up. The moon was emerging from the clouds, showing a patch of yellow light. I squinted as it brightened his profile. He looked dreamy as if envisioning running his own restaurant somewhere in Sendai with me sweeping the entryway.

The dark clouds were coming. Masa put his arm in the heavy black leather jacket over my shoulder and I almost lost my footing. A siren blasted in the distance, sounding like a high-pitched scream. The clouds were about to cover the sky as the moon cast its last light and made everything clear for me.

Yuko was born and grew up in Osaka, Japan. With a BA from Smith College and an MBA from Yale University, she has worked for nonprofits such as The Brookings Institution and Save the Children. In 2021, she retired from 15 years of teaching math and science in Japanese at an immersion program in Virginia. Her writing was nominated for the 2023 Pushcart Prize. Some of her nonfiction pieces have appeared in Arcturus (Chicago Review of Books), LIT Magazine; Hippocampus Magazine, the 34th Parallel, and Apple Valley Review.

Matt Bollinger received his BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute in Painting and Creative Writing and his MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in Painting. His work has been exhibited in solo shows in New York, Dublin, London, Paris, Los Angeles and elsewhere. He is represented by mother’s tankstation and François Ghebaly Gallery. He lives and works in New York state.