Jim

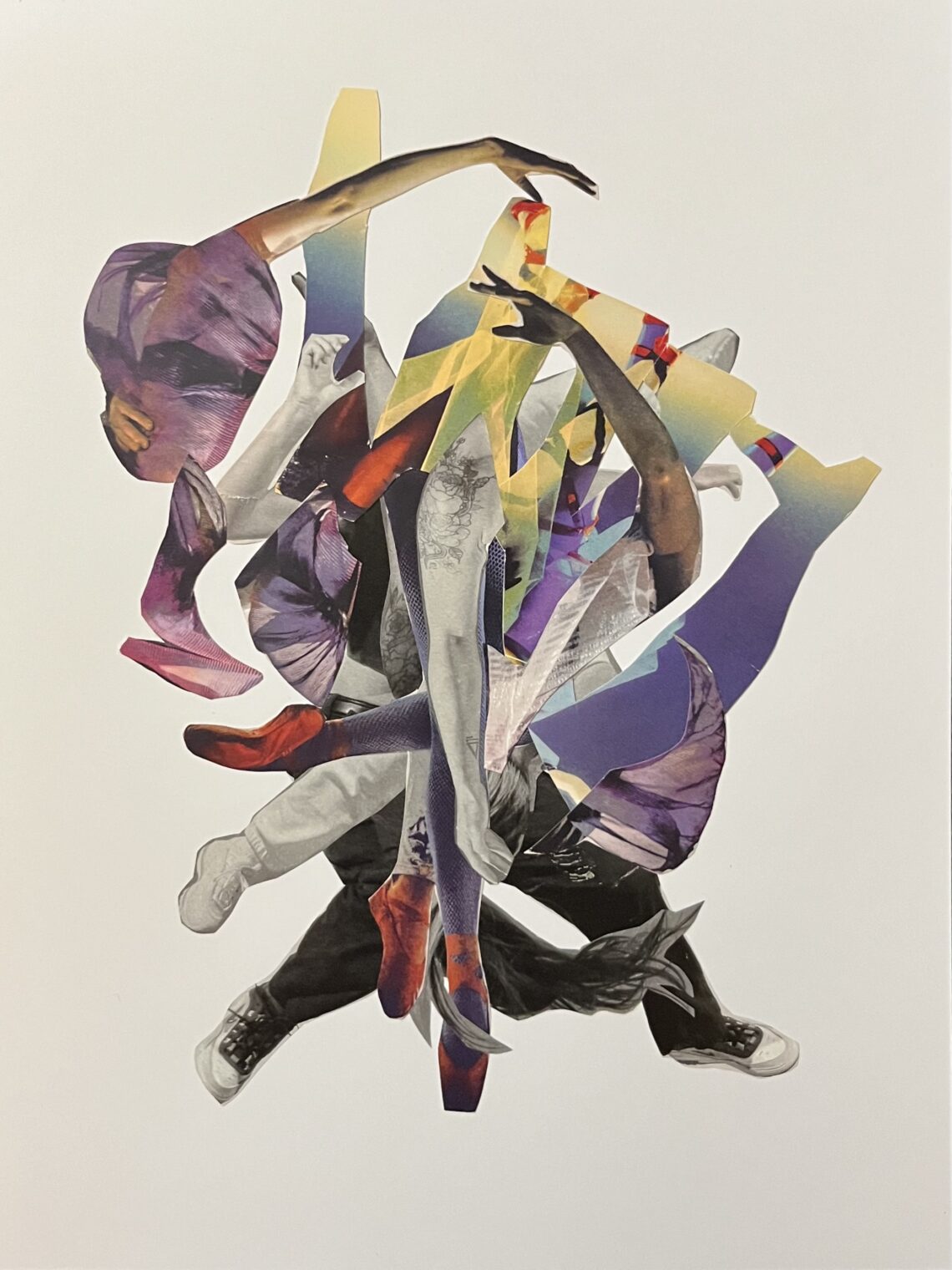

"Flare" collage by Tiffany Dugan

by Peter Allen

Since the beginning of term, I had been haunted by a boy at school, a boy with dark hair, pale skin, and features that looked as though they had been cut and polished out of some kind of white marble that had only the faintest tinge of warmth. Not that he wasn’t animated: I often watched him moving quickly across the playing field, or walking, gregarious, laughing with his friends as they headed off campus during a free period, disappearing around the corner of a leafy street while I lingered behind, holding a notebook, wishing I were there, just me and him, hand in hand. And sometimes he would notice me, if only for a moment, wielding a curious, penetrating gaze that stole my breath before I turned my eyes away, before I blushed.

I thought of him before I went to sleep every night, and wondered what it would be like to run my tentative fingers down his white back, down to the band of his briefs, to breathe in as he breathed out, to stroke that smooth, straight, black hair. I thought about him during the day, too. He was always in my head when I was on the subway steps, climbing up to the rickety elevated terminus on my way home, thinking about whether he’d noticed me that day and when I’d see him again; and then he’d be back with me before eight in the morning, as I was climbing down on the way to school.

I shivered, trading my bookbag to my left hand as I struggled with the zipper of my jacket. It was the beginning of October, 1969, and there were dried leaves blowing around in the trash in the gutters below—random newspaper pages, stained paper coffee cups, a cigarette butt still burning after someone had thrown it away at the beginning of the daily climb to the downtown local. The stop was 242nd Street, Van Cortlandt Park, and while it was the end of the trip for me, it was the beginning of the ride for most people, as they left Riverdale for Manhattan and the working day.

The wind blew colder. The whole sky was covered with grey clouds, dense in some places, translucent in others. Fall was early this year, and October already saw the trees mostly bare, the rutted, raw earth poking out, uncovered, in areas where the browning grass had been torn apart by a sliding baseball player or a troop of schoolchildren. I could see the wind blowing across the park, its icy clarity, tinged with cloud-grey, heading around and past me, off towards the river and south.

Shivering, I stumbled into motion, pushing my way through the crowds rising up to the station. Routine took over: I was down at street level and then climbed the four long, steep blocks, scarcely noticing where I was. Up the twisted concrete steps with their pipe railing, onto the roughly landscaped campus, into the brick monolith of Guggenheim Hall, to my locker, and up to the fourth floor, where I found the usual small cluster of seventh-graders outside the English classroom. I went over my homework with them without really paying attention: every other minute, I was looking down the hall toward the stairway, hoping to see Jim as he headed for his first class. I turned around so often that I could see the other boys starting to notice, following my gaze, so I stopped and turned back to the notebook in front of me.

“It’s a subordinate clause,” I pointed out, in an irritated tone.

“Oh,” said Braverman. “What’s a clause?”

I never was quite comfortable with Braverman. He had a certain swagger that was aggressive and seductive at the same time, and I could tell he kept an eye on me, showing an awareness of something in me. I didn’t know exactly what it was, but I knew he did, and he used that knowledge to keep me subtly under his thumb.

Despite the swagger, however, Braverman wasn’t particularly good at most of his academic work, and so he always found somebody to help him. In English, it was me.

“Looking for someone?” he asked.

“No. I just want to make sure Warriner doesn’t see me helping you with your homework.”

“Yeah, I bet.”

I blushed a little.

“You need a semicolon there, not a comma.” I attacked his punctuation—his weakest point.

English was uneventful; so was the next class, math. Then, at 10:30, I walked across campus to theatre class. Theatre was a new subject for me, and I didn’t quite get the point: we would sit scattered throughout the semi-dark auditorium, listening to the teacher tell stories about his career on Broadway, years before. My mind often drifted to homework—the next English paper, math problems I hadn’t gotten right on the last exam.

All of a sudden, I realized that Jim was sitting next to me, his hand on my arm.

“If you were a girl, I’d kiss you,” he whispered.

My heart stopped. What had he said? I stared at him, but he was looking away, focusing on Mr. Shorter, twenty rows ahead of us.

“If you were a girl, I’d kiss you.” The sentence echoed through my mind, resounding in all those crevices whose existence I’d hidden from everyone, I thought— but I was wrong.

My immediate reaction was to think that I had imagined this, but I knew I hadn’t. My second response was to wait for a kiss. I wasn’t a girl; he knew I wasn’t a girl; did it matter? Could I pretend to be a girl? What would happen if he kissed me? I started dreaming again, wondering whether I could cross the heavily guarded frontier of my isolation. Yet despite the strangeness of the moment, I was not anxious: I had wanted Jim so long, without even knowing exactly what I wanted, that when he let me know he knew, and that in some way he wanted me, too, a self-confidence I had never imagined suddenly took my hand.

Thinking back, it only made sense that this should have happened in the theatre, which was what had most drawn me to Hamilton. True, I’d been eager to benefit from the school’s academic reputation and prestige; and the fact that it had a real gym, playing fields, and a pool called to my urban, skinny-kid imagination, my desire to become bigger, stronger. The fact that all the students were boys hadn’t seemed like a bad thing, either. But when, as a sixth-grade visitor, I had walked into the theatre, I’d known that a school that contained this place was the school I wanted to attend. It hadn’t been clear why, since I had no particular interest in acting, but there must have been a premonition in the curving rows of blond wood seats, the modern pipe organ, and the shadows and lights of the stage, that one day I would be there with another boy next to me whispering, “If you were a girl, I would kiss you.” And on that day, I discovered that the barriers between inside and outside that had been an indispensable part of my childhood were, all of a sudden, transformed from concrete to paper, subject to a push, a knock, or, even more vulnerably, an imagined, and now spoken, wished-for kiss. From a boy. From Jim.

Nothing more happened then. The usual round of chores and preoccupations resumed: lunch in the cafeteria, earth science class, getting off the subway at 96th Street, on the way home, to pick up my little sister at the babysitter’s; Sunday school at the West Side Synagogue; homework every night. But every subway trip, every math problem was shot through with the glowing, golden threads of the kiss that Jim had almost offered that day in the theatre.

And that kiss—or, more precisely, the hope of that kiss—shaped not only my inner life but even my academic career. Our school had a subject called “General Language,” which we called “G.L.” To counteract the students’ tendency to gravitate to the most familiar languages, Hamilton had created this seventh-grade course. Between September and May, we were exposed to doses of Latin, French, German, Russian, Spanish, and the principles of Indo-European linguistics. The teacher enlivened the class with numerous eccentricities, adding elements like Daily Vocabulary, with odd terms like “zarf” and “strigil”; and other classroom sports, including dictionary-catching and the regular provocation of the designated Class Blusher, a sweet but shy fair-haired boy whose face, regardless of his will, invariably responded to the teacher’s command, “Blush, Paul!”

Latin came first in this parade of languages, and I did not like it. The problem wasn’t lack of motivation: I had conceived a goal of going to Oxford, where classical languages were required for entrance, and I had even tried to learn Latin on my own in sixth grade. But I just didn’t catch on to Mr. Dunhill’s instruction. Perhaps he didn’t clearly explain the principles of declension and conjugation; perhaps I simply didn’t yet know how to memorize effectively. In any event, I didn’t do well, and I remember being at my father’s house one wintry Saturday evening and typing, slowly, line by line, “I loathe Latin” on his portable electric Smith-Corona until I had filled an entire sheet of bond paper. Dad remembered it too, and quizzed me about the apparent incongruity when I signed up for five years of classical servitude. But I couldn’t explain it to him.

The reason was that Jim had enrolled in Latin for the following September. And as if the prospect of daily classroom contact were not enough inducement, there was also Stonyfield. Group by group, eighth-graders from Hamilton were sent up to the Richard Stonyfield Nature Lab, a piece of property in rural Connecticut owned by the school. The goal was to give us some experience in the world outside New York City, to toughen us up a little, expose us to something other than the race to the Ivy League. French and Spanish classes, being large, went up in batches, but the smaller language classes, like Russian and Latin, went up en bloc. And to me, in seventh grade, the prospect of spending a week in a lean-to in Connecticut the following year with Jim Thornton was enough to overcome my fear and loathing of ablative absolutes and perfect passive participles. I admit it: I took Latin so I could spend a week in the wilderness with Jim. But I couldn’t say that to my father at the time.

Seventh grade ticked forward. On cold winter days, we would dash across the gray Bronx campus, from the pool to the cafeteria, our wet hair freezing in strands in the icy wind and melting, drop by drop, as we waited in the cafeteria line for lunch. If I ran into Jim, I would smile, and sometimes get a hi or a knowing look—or, if he was in company, as he often was, only an embarrassed sideways glance. Jim was popular in a way I wasn’t: while my acquaintance progressed stepwise, one by one, his social circle broadened out in round, magnetic ripples, with no apparent effort on his part. He was beautiful, and charming, and flirtatious; boys came to him, sought him out.

Jim’s closest friends, as far as I could tell, were three very different boys. The one I liked the least was Nat Engel, a small kid from some paunchy New Jersey suburb inhabited by mothers on Valium and cigar-smoking fathers in Cadillacs and Lincoln Continentals. Engel seemed to me kind of a juvenile delinquent, or at least as close to that as boys could be in a highly competitive, predominantly Jewish New York prep school at the turning of the ‘seventies, which was not very much. But Engel and Jim and other boys from cliques I didn’t know would wander off campus during study hall periods and smoke dope on the curving streets of Riverdale, in the shadow of large, manicured houses deserted for the day by their city-employed owners.

The second of Jim’s close friends was Randy Braverman, the Boy Who Knew Too Much. Braverman was an anomaly in the class in many ways. He had reached puberty early, and was bigger than most of us; and somehow he was gay and out, though we didn’t have these words or even concepts, and were completely unaware that the history-changing Stonewall rebellion had happened in Greenwich Village just a few months before. But even at 13, Braverman was surprisingly confident in his sexuality. He would walk into math class before the teacher arrived, look around at the rest of us, and announce, “Hello, girls.” And I heard from Jim that Braverman had initiated a number of boys in the class into sex—including Jim himself. I had no desire to get any closer to this dangerous young man than I already was, but he somehow dominated us, and it was strange but not entirely surprising that we elected him president of our class.

The third of Jim’s close friends was Jeremy Kazan, a patrician among the many Jews at our school. Tallish and slim, Kazan had full brown bangs, a delicately featured face, and a quiet, slightly hesitant elegance that invited protection. If I had been taller and older, I might have fallen in love with him; as it was, we revolved around one another in our spheres, crossing paths without ever getting too close. He too fell into the circle of Jim’s charm, and for a while they were inseparable, though Jim would never tell me whether they had sex. Eventually Kazan drifted off into a tight bonding with Eberhart, a handsome basketball player from New Rochelle with whom he would remain intimately, if seemingly Platonically, paired through college and beyond.

Couples were not unusual in our class. Sometimes the boys involved had sex; sometimes they didn’t. The rest of us would watch and speculate, but we didn’t find the connections shocking; they were just how we bonded with one another in this pressured, young, male environment. And when boys made plans to get together outside of school, we would say we were having a “date.” My stepmother tried to correct me once: “Boys don’t have dates,” she told me. I shut her down, though: “We call it a date.”

I watched and waited, hoped and suffered. Winter thawed into spring. In Central Park, the fresh season was marked by pussy willow buds and wafting boughs of forsythia hanging yellow over the transverse roads, 66th Street, 79th Street, 86th Street, stirred by the breeze of cars, yellow cabs, and green crosstown buses. On campus, our roster of sports rotated by the season. Winter had a demoralizing insistence on basketball (which, being small and not well coordinated, I was useless at), though the cold months were somewhat redeemed by the intimate enticements of swimming and wrestling. Spring brought the outdoor pursuit of baseballs, tennis balls, and golf balls, the better to prepare us for our future lives as members of the business class. And as the weather grew warmer and we started wearing sneakers and left our coats at home, the date of Mr. Lawson’s Washington trip arrived.

Stan Lawson, with his graying brush cut and short-sleeved white dress shirts, was a legendary figure at the school, from which he had graduated 30 years before. Every seventh-grader had Mr. Lawson for American history, and as a class we memorized the preamble to the Declaration of Independence, the names of the Supreme Court justices, and the racist machinations of the Three-Fifths’ Compromise. We listened to Mr. Lawson’s lectures on the importance of a single vote in a close election, and to his confessions, no doubt repeated every year, but also no doubt true, that had he lived in the American colonies at the time of the Revolution, he might well have been a royalist, given his antipathy to change.

Change did not come easy to Mr. Lawson. He admitted that he resented the fact that the school had abolished its dress code the previous year. If he saw a boy in jeans, let alone the newly fashionable bell-bottoms, he would stop the student and start to lecture him about proper attire—and then realize, halfway through, that the regulatory basis for his reprimand had vanished, and he would sputter, and stop, and walk away shaking his head.

It wasn’t just bell-bottoms: Mr. Lawson was fascinated by pants in general. Sometimes, during class, he would unbuckle his belt and adjust his shirttails over his boxer shorts. “I guess I won’t be able to do this when they let girls in here, eh, men?” The oddness of the scene was striking, even then: the suppressed and heavily denied eroticism of Mr. Lawson’s self-exposure, his anxiety in the prospective presence of girls (a fear that seemed to haunt many of the school’s teachers), and the absurdity of addressing a group of twelve-year-old boys as “men,” as if we were a group of Marines.

Stan Lawson wasn’t the only teacher who behaved inappropriately with us. In fact, years later, it came out that many of the faculty members were having sex with students, and since the school was prominent, the story flooded the pages of all the New York media. But it was Lawson who opened the door to what I had been hoping and waiting for for months.

To augment the schoolteacher’s salary on which he supported his large Catholic family, Mr. Lawson was a small-scale entrepreneur. He made some extra money by driving a van full of boys from Connecticut and Westchester to school every day, but the bigger enterprise, the one that touched far more of us, was the Washington trip. Over spring break every year, Mr. Lawson would charter two buses, fill them with seventh graders, and bring us all to the nation’s capital, where we would walk among the institutions we had been learning about all year. We had visits to the Senate, with its odd little subway; to the monumental architecture of the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials; to Arlington National Cemetery and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier; and to the National Gallery of Art. It was worth it, I guess, for educational purposes, but more important to me were the iridescent opportunities the trip offered to be close to Jim.

Per tradition, our class stayed in an aging hotel where, for reasons of economy or propriety, we were lodged in threes: one in each of the rooms’ double beds and the third on a rollaway cot. I shared my room with Tim Garber, a gregarious, smart, if slightly neurotic boy from upper Manhattan (eventually, like so many of my classmates, to become a lawyer) and with Dave Zambrino, who had a broad smile but was not a gifted student. Zambrino, unlike Garber, did not go off to a professional career: When I met him at our tenth reunion, he was dressed in a mismatched jacket and pants and shiny tie, driving trucks for a dairy company.

Among the bustle of these and other classmates the trip advanced, day by day, with the expected amount of noise and bickering, as well as a good deal of flirtation, jealousy, and sexual innuendo. And as our bus drove to the National Archives, I sat next to Jim.

“Do you know about wet dreams?” he asked me, with a little smile.

“No,” I said, sensing that the conversation was moving into exciting, dangerous territory. Nobody else talked to me about sex, certainly not like this, and I could feel a warmth spreading from my groin to my chest.

I realized that Jim was leading me where I most wanted to go, where I didn’t dare to go, and I changed the topic.

“I saw you steal something from the souvenir shop,” I said.

“Oh, you did? So what?” There was that smile again.

“You could get into trouble, Jim.”

“I guess I could . . . .”

I was the good boy to his bad, and our differences in temperament and behavior excited both of us. Jim was the boy who broke the rules, offering to me a world of unknown pleasures and risks; I was the compliant model student he could tempt beyond his limits, exercising his power and attractiveness, but also entering into the black-and-white intensity of my moral sphere. Did he like me because he was attracted to me, or was it because I made him feel powerful? I couldn’t tell. Maybe it was both.

And in my head, underneath every conversation, every calculation about where to stand in the line of boys waiting to get back into the bus so that I could sit next to Jim, was the never-voiced question, “How can I get him to kiss me?”

Surely he could feel this, and surely he wanted it, too. Without entirely acknowledging where things were going, we looked at the various angles and how to create the opportunity. By the final night, we had managed to convince Garber to change rooms and roommates, and Jim was bunking with me.

Lights out, Zambrino, Jim, and I piled into one of the two double beds. We talked; we groped. There was a hand on my hand, a hand on my chest, and then a star exploded and I felt someone’s lips on my mouth. Jim was kissing me, and I couldn’t think of anything else; I couldn’t think. It was happening.

That night changed my life.

I don’t think it did for the other boys. Zambrino probably doesn’t even remember it. For Jim, it was a moment in his relationship with me, but maybe not an important one. Later that spring, the night before my bar mitzvah, he stayed over in my apartment, and we went a couple of steps further. And throughout the rest of our years at Hamilton, we continued to flirt, and have sex, and exchange letters which we delivered through the air slots in one another’s lockers. When Jim’s parents found my letters, there was a confrontation, and then I wasn’t welcome to visit their house anymore, even though Jim was the one who had seduced me. But Jim also slept with other boys, and even girls, so I was just one conquest among many. Part of what made him so exciting was the fact that he was a serial seducer, an adolescent Don Juan, and the first boy to break my heart.

But there, in that double bed, in that hotel, on Stan Lawson’s Washington trip, in the spring of 1970, none of that had happened yet, and though it would happen later, though the outlines of the story were already laid down, the fractures of my emotional life starting to show, none of it mattered. For me, it was magic. Because even though we weren’t in the theatre, and even though I wasn’t a girl, it was the night I got a kiss from Jim.

Peter Lewis Allen was educated at Haverford College, the University of Chicago (Ph.D.), and Wharton (M.B.A.), and has taught at numerous universities, including Princeton and Yale-National University of Singapore College. Publications include articles in The New York Times, The Chaucer Review, the MIT Sloan Management Review, and the McKinsey Quarterly and books published by the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Chicago Presses.

Allen lives in New York with his Singaporean husband, Jet Heng.

Tiffany Dugan grew up in a California creek town and lives in the big city. She makes art and writes in her home studio in Inwood, NYC. She has exhibited in 30+ solo and group shows and is in collections throughout the US and Europe. Publishing her work in literary magazines bridges her love of art and writing. She received the Sarah Lawrence College Gurfein Fellowship in Creative NonFiction (2019) and wrote a memoir “Love and Art” about growing up the creative daughter of an abstract painter and the art legacy she inherited after he died. Tiffany went to Sarah Lawrence College (BA) and is a proud Milano, The New School alumna (MS). For more of her art, visit W: tiffanydugan.com IG: @tiffany.dugan