Leather Jacket

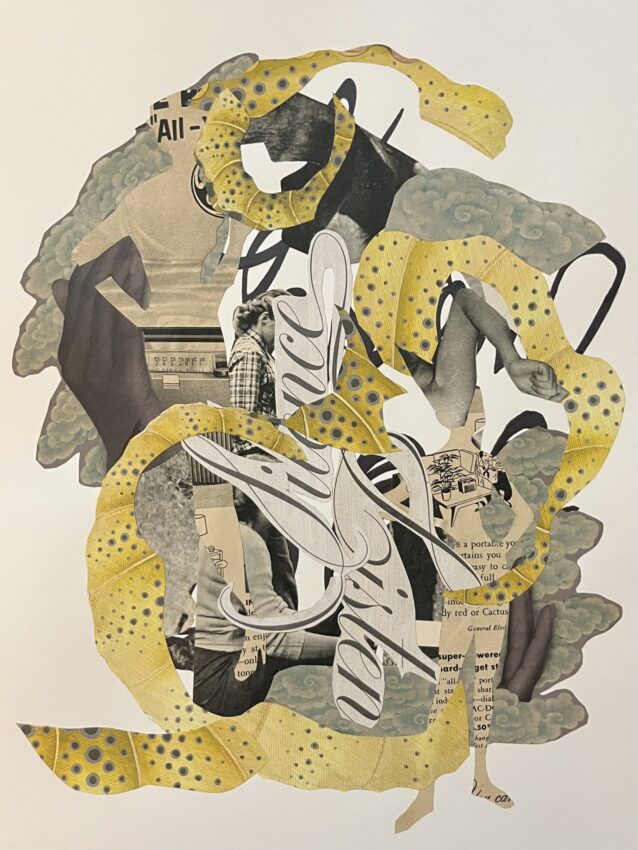

"Primarily Black and White" collage by Tiffany Dugan

by Sarah Seybold

In eighth grade, I ached for a leather jacket. The kind the popular people wore. A brown bomber with a world map lining the inside.

I saved for months, nearly a year. Babysitting money from the single mom down the road. Long hours after school, changing her toddler’s poopy diapers and chasing her two little girls whose hands were stinky from Cheez Whiz. Their small, musty house even messier than my own cluttered trailer. Occasional weekend jobs in town for the Air Force major and his wife. Their well-behaved blonde triplets already bathed and pajama-footed when I arrived. Their large house so neat and clean I was afraid to touch anything.

Last week of December, my mom drove me to the mall for the after-Christmas sales. I searched all over Sears, JCPenney, and Roots, trying to find the perfect leather jacket. But that late in season the only coats left dangling from the shiny metal racks were too ugly or too big. I felt embarrassed being with my fat mom who plodded so slowly along. I hoped I wouldn’t see anyone I knew from school. I hoped no one would see me.

I worried as we walked into Elder-Beerman, the last department store left. The fanciest and most expensive. My mom and I wandered, lost and overwhelmed, past the dizzying smells of the perfume and make-up counter, the careful order of the fancy dress shoe displays, the neat organization of the home section with uniformly folded towels arranged by color, the well-tended rows of women’s clothing and lingerie, until we found the coat section in a quiet corner at the back of the store.

I knew instantly when I saw the jacket, hanging on the picked-over rack. An expensive bomber, the exact style I wanted. Marked half off for the after-Christmas sale. Dark brown, a shade darker than what most popular eighth grade girls wore. But I decided I loved that, mostly. A jacket slightly different but not too different.

A saleslady with salt-and-pepper hair and kind eyes asked if I’d like to try on the jacket. She was the first person in the mall to offer help. She unlocked the security cord, removed the jacket carefully from its sturdy hanger, and opened it to me, and I could see fully the map print inside, the shades of brown and tan indicating mountains, rough terrains, oceans marked between continents. I slipped in each arm easily. The slick lining slid smoothly over my shoulders. A perfect fit. I couldn’t believe I was trying on something so expensive. I was wearing a map of the world.

I had to have that jacket. But I worried I didn’t have enough. The woman down the road didn’t pay me much to watch her kids. The Air Force major paid me a lot more than she did, but those jobs were rare. And there had been all those times my dad’s child support checks hadn’t come. I’d given my mom money for groceries, McDonald’s, her prescriptions, and bills.

I took off the jacket and returned it to the saleslady. She looked at it admiringly as she hung it back on the hanger and placed it on the rack beside the cash register. She smiled warmly at me and said I’d found a good bargain, such a nice coat for the price. My hands shook as I took money from the envelope I’d kept tucked under my mattress. All those dollar bills softened from the times I’d spread them across my bed, smoothing them out, recounting. One hundred dollars. Exactly enough.

After she closed my money in the register, she gently draped a thick plastic Elder-Beerman shopping bag over the coat. She took her time to bend down and carefully tie together the bag’s corners at the bottom. As she prepared the jacket to leave the store, she mentioned I’d need to get a protective spray to waterproof the leather.

My mom seemed exhausted and distant. She stood awkwardly beside the checkout counter, unable to stop yawning.

The last days of Christmas break I was stuck at the trailer. It stunk from the overstuffed garbage can, piles of dirty clothes, and unwashed dishes towering beside the sink. I couldn’t stand my mom’s clutter. The kitchen table was covered with old newspapers and unopened mail, wadded up McDonald’s wrappers, and empty plastic bags from the pharmacy. And the floor needed to be swept. Food crumbs and tracked in dirt clung to my bare feet or grayed the bottoms of my socks. There was always so much mess to clean, but I never knew where to begin.

I kept going to my bedroom closet to peek at the jacket. I’d untie and lift the plastic bag so I could take deep breaths of the rich leather smell. I always made sure my hands were clean and dry before removing the jacket from the strong hanger and trying it on again. I loved how the leather felt on my shoulders and back. A pleasant weight.

I wore the jacket inside for just a little while at a time. I wanted it to stay new forever. Through the dim hall, I walked back and forth, stopping to look at myself in the full-length mirror. I felt rich, like those rare occasions when my mom was better, the trailer tidied, and the bed sheets clean and fresh, pulled tight against the mattress.

I imagined myself walking proudly through the locker-lined halls at school. I imagined blue-eyed boys saying hi to me during passing period and flirting with me during band and lunch and me knowing how to flirt back. I imagined being friends with the popular girls, their crimped blonde hair always perfectly styled and their new well-fitting clothes neatly pressed. Those girls who’d had their leather jackets for more than a year, bought at full price. Maybe now that I had my leather jacket they wouldn’t notice my flat brown hair with split ends, my too long bangs, my thick dorky glasses, and cheap Payless shoes with that growing hole in the sole I hid. Maybe they wouldn’t notice I had just two pairs of jeans, both too short, too tight. The waistband and rough seams pressed into my belly and hips, leaving marks and indents on my skin.

Mostly, though, I imagined myself no longer so afraid to talk. I pictured myself raising my hand in class instead of keeping my head down, trying to avoid eye contact, hoping the teacher wouldn’t call on me. My face would burn, and my stomach would churn when I had to talk in class. I wanted to speak, but by the time I mustered enough courage and energy to get the words to my mouth, somebody blurted out something else, and everybody moved on while I stayed quiet and dumb, still going over in my head what had just happened. But I was finally going to change all that. In my diary I hid under the mattress, I’d written my New Year’s resolution in swirly cursive with hot pink ink: Stop being shy! Be confident!

The night before school started again I could barely sleep, so excited to wear my jacket. I worried, though. What if something bad happened? What if the jacket got damaged? What if something got spilled on it? What if the soft leather got scratched? What if someone stole the jacket from my locker?

I also worried about the waterproofing spray the saleslady had mentioned, but I didn’t know where to buy it or how much it cost. I mentioned it to my mom a few times, but she said she didn’t know either, and we’d figure it out later. And then she’d take a nap. She was too tired to drive all the way back into town. And too sad. Crying in the car, crying in the shower, crying in her bed. Always crying or sleeping. I didn’t know what to do about my mom. And I had no money left.

In the morning, I opened the door to rain. A cold January rain. I wondered for a second if I should leave my jacket at home. But I was afraid if I did, people would think I didn’t get anything for Christmas. And I didn’t want to wear the ratty pink too-short Kmart coat with the stained cuffs and chipped oblong buttons I couldn’t fasten around my waist anymore.

I stepped out the trailer door and onto the porch, lugging my clunky saxophone case and my scuffed backpack slung over one shoulder, filled with all my textbooks I’d brought home over break, though I didn’t need any of them, my gym clothes, deodorant, and those flat pretend Keds that hurt my feet. I worried my heavy backpack would scrape my nice leather.

As I stepped out from under the porch roof, morning dark as night, I realized the rain was harder than I thought. I ran down the cinder-block steps toward the chain-link fence, flung open the wet metal gate, and headed for the side of the garage to wait for the school bus. On the way, I heard each fat raindrop plop the leather on my shoulders.

Under the garage’s narrow awning, I hunched, trying to make myself small, praying for the rain to stop, for the rain to quit splatting my leather. But rain started rushing off the garage roof, a cascade in front of me. Water gushed from the gutter and bounced up off the driveway gravel. I held my breath. I felt my throat close. An ache under my cheekbones. A surge straight to my gut. I’d messed up.

I thought maybe I should run the bomber back inside, but it was too late. I heard the bus chug down the country road, saw its white strobe light flash leafless trees in the distance. When the bus turned the corner at the cemetery, it was time to run up the side road to the bus stop. As the bus approached, its light kept flashing our home. The hail-battered trailer, the dumpy car, the muddy pen with the chained-up dog, the short pumphouse with a growing hole in the roof rotting over our well.

And the embarrassing brown garage beside the trailer. Years ago, before my dad had left, he’d splashed a bucket of white paint in an angry arc across the siding. Paint had dripped in lines from the underside of the arc. When I was younger, I tried to pick off the paint with my fingernails, starting with the dried bubbled globs at the bottom of each line, but my nails chipped, and my arms got tired, and I didn’t get very far. The ugly streaks still clung to the dirty brown metal.

I darted through the rain pouring off the garage roof and ran up the side road as fast as I could. But I was awkward, slow, and out of breath. I felt the quickening raindrops pellet my jacket. I huffed up the bus steps and walked the dark aisle to the back row. My leather smelled like wet dirt.

At school I walked into the bright gym where students waited on the bleachers until the bell rang. So much of junior high took place in that space. Pep rallies, band concerts, award ceremonies, dances, gym class. That morning everyone’s wet shoes squeaked as we walked across the slick gymnasium floor. That shiny floor the fat girls swept.

Each grading period, when we had to run the mile for the Presidential Fitness test, the gym teacher made the two fattest girls in eighth grade clean the floor instead. While the rest of us ran laps, those girls walked slowly behind wide janitor brooms, pushing dirty gray clouds of our hair and dust around the edges of the gym.

I hated to run the mile. I was always so far behind. Out of breath with a painful stitch in my side. Plodding along with those flat cloth shoes. And the pull-ups test was just as embarrassing. I felt sick waiting in line for my turn. I could barely heave myself up to reach the metal bar. And when I did finally manage to grab ahold, all I could do was dangle there.

In gym, I wasn’t picked last for teams, but I was always picked next to last. I hoped the teacher would never make me sweep the floor, too. I wasn’t as fat as those couple big girls, but I didn’t have a perfect figure like the popular girls either. I worried I’d get fat like my mom someday. I already had those ugly streaks I couldn’t make go away on my belly and hips.

One day in the locker room, some popular girls noticed those lines. She’s got stretch marks! She’s got stretch marks! They chanted and laughed when I had to walk the classroom aisles to turn in an assignment at the teacher’s desk, or when I walked through the cafeteria with my head down, trying not to drop the tray. She’s got stretch marks! She’s got stretch marks!

That January morning everyone looked so clean and fresh, rested from two weeks off school. Under the bright yellow gym lights, they all gloated about what they got for Christmas: Liz Claiborne purses, Benneton bags, Esprit shirts, Guess watches, and Guess stonewashed jeans with the triangle label on the back pocket. My sock was soggy inside my holey shoe. The bangs I’d teased high that morning drooped, weighed down with wetted hairspray, and stuck to my forehead.

I looked down at my arms and shoulders. Under those blaring lights, the rain streaks dried into slightly raised, shiny lines. Ugly and permanent. I slumped in the gym, trying to make myself small, hoping no one would notice my jacket. The leather that held me as I looked in the mirror was no longer perfect. Ruined.

Sarah Seybold’s poetry and prose are published or forthcoming in Alaska Quarterly Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, ZYZZYVA, Arts & Letters, The Indianapolis Review, Great River Review, and elsewhere. She grew up in Terre Haute, Indiana, and earned her BA in English and Gender Studies from Indiana University and her MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Oregon. She lives with her husband and daughter in Columbus, Ohio. Sarah is on Bluesky @sarahseybold.bsky.social.

Tiffany Dugan grew up in a California creek town and lives in the big city. She makes art and writes in her home studio in Inwood, NYC. She has exhibited in 30+ solo and group shows and is in collections throughout the US and Europe. Publishing her work in literary magazines bridges her love of art and writing. She received the Sarah Lawrence College Gurfein Fellowship in Creative NonFiction (2019) and wrote a memoir “Love and Art” about growing up the creative daughter of an abstract painter and the art legacy she inherited after he died. Tiffany went to Sarah Lawrence College (BA) and is a proud Milano, The New School alumna (MS). For more of her art, visit W: tiffanydugan.com IG: @tiffany.dugan