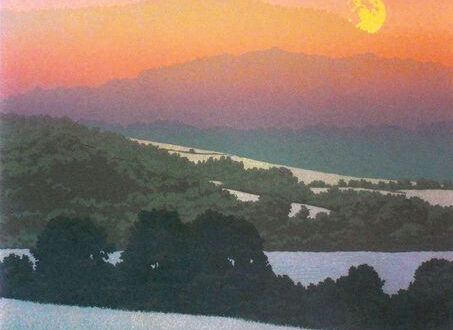

My Father’s Iris

Art by Andy Mister

by Marilyn Martin

Nine years after my father died, my mother dug up a clump of wild irises from behind the New York suburban house where she still lived and where I’d grown up. At the time, my two young children and I were visiting, and the evening before we were to leave, my mother tenderly swaddled one iris in damp paper towels and placed it in a shopping bag. On the plane, the iris balanced between Sara and John who put their arms around it as we cruised 30,000 feet above the earth.

A few days later, I planted the iris in our garden in suburban Chicago behind the black-eyed Susans and coneflowers. Standing upright, the plant’s sword-shaped leaves measured up to 2 1/2 feet, almost as tall as a two-year old, and while I smoothed the soil around its roots, Sara and John bounced from foot to foot. I don’t think the two of them understood why the iris meant so much to me even though I’d explained it. They were only ten and six, and my father had died in 1983, the week of Sara’s second birthday; two years before John was born, so no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t find the words to make him come alive for them.

Still, when it came to figuring out my feelings, my children were human Geiger counters. If I were excited, they were excited. After I planted the iris, Sara and John asked to phone their dad at his office to tell him all about it. It was late August. I was eager to see the iris bloom in spring.

*

In 1957, right after my parents, baby sister and I moved into our first and only house in a postwar suburban subdivision, my father began to travel with a spade in the trunk of the car in case he spied a specimen while he was running errands.

He aimed to replicate a northern deciduous woodland, the dominant landscape in our part of New York, along the western boundary of our property. The maples, oaks and white birches were already growing there, and on weekends when he wasn’t at the lab, I trailed after him as he constructed a wall of boulders and began filling in the area between the existing trees with rhododendrons and dogwoods he’d dug out of the forests along the roadways.

Like my own children and the iris, I didn’t fully understand what this project meant to him. Turning our side yard into woodland took five years, and my father wasn’t really a gardener. Still, he was a person driven by a relentless curiosity, particularly when it came to native plants and animals so his mini-woods was the perfect undertaking for him: a low maintenance, self-supporting system that he could fashion by observing the natural world.

I found his insatiable curiosity contagious. Once, when I was much older, I got up at sunrise to explore gardens with him in the neighborhoods next to the motel where my family was staying overnight in South Carolina. When the other members of my family heard Dad moving at sunrise, they moaned, pulled pillows over their heads and kept sleeping, but I wanted to go. As he and I hung over white picket fences taking in Spanish moss and camellias, his need to puzzle things out buzzed around me until Ifelt those flashes of light settle inside me.

His curiosity served him well as a research chemist who was tasked with finding antibiotics for a pharmaceutical company. “Finding” struck me as a strange word as if my father walked up and down the corridors at Lederle Laboratories searching like Lucy Locket who lost her pocket. To me, he was more like the explorer Henry Hudson who I’d been taught had “discovered” the Hudson River, since Dad uncovered new antibiotics after searching through living and nonliving things like mushrooms or soil.

I loved being his accomplice on his plant reconnaissance missions particularly since whoever owned “the woods” was a mystery, and Dad usually so law-abiding–he refused to cross against the light–wasn’t the kind to trespass. This was in the late 1950s, early ‘60s, when our county was transitioning rapidly from a semirural landscape to a suburban one, so the notion that Dad and I might be stealing from the contractors who cut down the trees and turned the land into tract housing made me feel like Robin Hood. I reasoned that the forest must be like the ocean, a place Dad said everyone should have access to even if it meant crossing privately owned land to get there.

In the beginning, I could barely see over the dashboard, but I’d note my father’s eyes combing the woods on either side of 9W while he turned the steering wheel with one hand and smoked a cigarette with the other. When he caught sight of something he wanted, he’d pull over onto the shoulder, retrieve the shovel from the trunk, and disappear into the woods until he re-emerged, grinning, holding up an uprooted mountain Laurel. I helped him lay the plants on newspaper and rope the trunk shut before we rode home on back roads to steer clear of trouble.

When I was older, I helped him choose the plants. By then, I could rattle off their common names as easily as a jump rope song–dogtooth lily, sour grass, lady slipper, princess pine, ghost pipes, May apples, skunk cabbage—so when I spied something along the side of the road my father needed, I shouted it out, and he pulled over.

Every tree and rock formation I glimpsed from the window were familiar to me, but for my dad, who’d grown up in the boreal forest 2,750 miles from New York, everything was new. Both my parents were from Canada and on the day we moved into our house, they had only lived in the United States for five years. My mother was from Edmonton, Alberta, a six-hour drive north of the US border. Drive six hours farther north, and you’d arrive in Fairview part of “The Peace River Country” where my father hailed from. Flowering dogwoods were not native to Alberta, so perhaps the northern deciduous forests were for my father as exotic as those gardens in South Carolina would later be for me. His side yard a woodland homage to a new topography.

The creation of my father’s northeastern woodland coincided with a time of national optimism as postwar entitlement programs made it easier at least for white middle class families like my own to obtain a mortgage and buy a house. Even though I was too young to understand the history, I felt the collective hopefulness vibrating around me the way I sensed my dad’s relentless energy. My father, the scientist who never thought he’d go to college, was married to my mother, the father of two, soon to be, four children, and was making good enough money to finance the green Cape Cod with its wooded half-acre.

On summer evenings, as we kids trailed after them, my mother and father surveyed the dogwoods and flowering cherries blooming on our property. True, our green Cape Cod was basic, designed to provide “the best shelter for the least price,” but for my parents, who’d traveled almost 3000 miles, then moved six times in five years, the days of renting rooms in other people’s houses was over.

They didn’t have much, but they had what they needed. “Man of property,” my mother teased as they surveyed everything coming up sweet and green. As far as they were concerned, there was nothing John and Bernadette Martin couldn’t accomplish as long as they had each other.

*

Back in Chicago, I was excited when the first green shoots of iris pushed through the dirt in late spring 1992. Wild irises die back in winter, and they also preferred swampy and marshy places, so when the iris my mother gave me emerged from the earth, I figured it had adjusted to the drier conditions of my herbaceous border.

In the evening, after supper, Josh, Sara, John and I walked the length of our garden as the tulips, peonies, and the climbing roses bloomed in succession and the iris regained its former height. I knew that transplanted plants did not usually produce flowers the year after they’d been uprooted, and also that wild irises were particularly loath to bloom when relocated from one place to another. Still, I was hoping.

I visited every morning after breakfast, longing for a hint of purple, but nothing. I was certain the next year would be different. I was bereft when the iris did not bloom that year or the one that followed or the one after that.

*

The spring I turned ten, my father asked me if I’d seen any wild irises in the woods in the vicinity of our neighborhood. He needed one, he explained, to plant in the side yard.

By local custom, the neighborhood woods were not a place for adults. We kids played there, but adults stayed out as if a wood goddess had erected No Grownups signs at every entry. But I knew every inch of it, so after I told Dad I knew where an iris was growing, he went to get the shovel.

We followed a convoluted route. When we first moved into our house, the woods was visible from the kitchen window, but now, five years later, the trees that once dominated the landscape had been reduced to an archipelago of forested islands scattered among suburban housing, making it impossible to go anywhere in the woods without detouring through backyards and streets.

Dad and I turned left onto Virginia Street. I almost never knew something that he didn’t. Guiding him was something I had to get right. I worried that I would misremember where the iris was or that someone else had dug it up. I felt my heart drumming like a metronome.

At last, we cut through the backyard of a split-level so new that it didn’t have any lawn, and ducked into a narrow corridor of trees bordered by the traffic on Route 304. We followed the stream for a while.

“There it is,” I called out, pointing to a spot just before the stream was directed through a culvert and then underneath the parking lot of a two-store strip mall. I steadied the iris while Dad loosened up the root ball. After the plant was completely excavated, its roots encased in mud from the stream turned out to be bulkier than we’d anticipated. Dad said he’d run home and get the car and park it in the meat market’s parking lot while I stayed back to guard the plant. That way we wouldn’t damage the iris when walking back.

By the next morning, the iris was growing in our side yard in a spot next to a dogwood where water pooled in rainy weather.

*

When I was a child, I didn’t understand the correlation between what my father did in the lab with his desire to acquire wild irises or to replicate native forests. But he started out in mycology, the study of fungi, originally classified as a branch of botany for the pharmaceutical company, Merck in Montréal, where I was born. Then, when I was a only a few months old, a fellow Canadian chemist convinced my father to emigrate to the United States to join a new lab at Lederle Laboratories, a conclave of stark, brick buildings nine miles from our home.

On Saturdays, he and I might be returning from buying apples at Tice’s Farm or excavating day lilies in an abandoned field when Dad detoured into Lederle’s parking lot, announcing he’d be back in a minute, a minute often stretching into three quarters of an hour. I watched him stride up to the guarded entranceway, exchange pleasantries with the attendant, and then he’d disappear from sight, as if an invisible curtain had fallen pulling him further and further away from me.

I did not resent the waiting even though it required fortitude. In an era with no Internet or iphones, children were expected to deal with tedium. If my mother and siblings were in the car, I “drove” them to Maine or if Dad were really delayed, to California. If I were by myself, I daydreamed, made faces in rear-view mirror, or stared at the attendant in the booth, willing Dad to reappear. When he finally did, he apologized, promising an ice cream cone or some other treat.

When I got older, I wondered what it must be like to discover a topic you were so curious about you never stopped thinking about it. Because I’m not sure Dad ever switched off the part of his brain that thought about chemistry. Rummaging through the kitchen junk drawer, I found chemical formulas scribbled on envelopes or grocery receipts among the spare shoelaces, the scotch tape and the change. Many nights, he’d barely finish dinner than he’d grab his car keys, announce he needed to adjust a pump or other apparatus, promising he’d be back in a jiffy, a jiffy a unit of time as elastic as his minute.

Even if Dad’s lab was closed to me, so much of what he did there spilled into our family life and dinner conversation that our Cape Cod felt like an outpost of Lederle. In school, I wrote with Lederle pencils, calculated my math homework on yellow legal pads from the lab and celebrated holidays with two other Lederle families whose extended families also lived in other countries. Once, dad brought home pure tetracycline powder, which he stored in kitchen cabinet in an effort to save on doctor bills when my mother was suffering from repeated bouts of strep throat.

I was desperately proud of him. My mother told me that he and his colleagues were engaged in important medical research unlike chemists who dreamed up formulas for Breck shampoo or perfumes, products Lederle also manufactured. I understood that his work was stimulating, but I also recognized it had a darker side.

His career coincided with a time of massive innovation — 95% of antibiotics in use today were invented then– but also a time of feverish competition among drug companies. Dad watched friends let go when they didn’t produce enough, and others fired a few months away from retirement, so Lederle wouldn’t have to pay their pension. Losing his job terrified him. If a project required him to handle foul-smelling substances or to stand in direct radiation as he did for a couple of years, he didn’t object. For the duration of the “skunk” project, he removed all his clothes at the backdoor; then, he jumped into the shower before he sat down to eat.

At dinner, he railed against a system that often favored profit over science, particularly when Lederle started selling tetracycline as a growth promoter for chickens even after Lederle’s own staff veterinarians counseled that adding antibiotics to chicken feed would lead to antibiotic resistance. If only he had a PhD, he once told me, he could work for a university; conduct his own research; not be a pawn of industry.

Still, Dad’s work was exciting. We cheered him. I knew whenever he produced crystals, a sign he’d isolated an antibiotic, he brought home ginger ale and ice cream. We toasted him, calling out skal, fervently hoping his antibiotic made it through further testing so his name could appear on yet another patent.

In the end, he wasn’t fired, but he wasn’t able to retire either. He’d put in his time, and in 1983, the same year my first child turned one, he was two years away from retirement after thirty-one years of pouring chemicals inside a small building that I would never see.

*

Back in Chicago as the years inched closer to the millennium, my father’s iris broke through the soil every spring, taking up its established spot at the head of the border. I no longer expected the plant to flower, accepting the way its tall reedy leaves tumbled over and made a mess in the garden. It was enough that my father’s iris had survived. It reminded me of so many passages: my father’s death, the disappearance of the woods where I played as a child, the way the pastoral world gave way to the suburban. The least I could do was to preserve it.

Then, one Saturday, sometime in the late 1990s, I stepped outside in the early morning to be greeted by a single tightly coiled cocoon-like bud peeking out of one of those grassy iris leaves. I didn’t believe in a transcendent being, but I felt tears well up. Even though my father would have insisted that what I was seeing was a biological process — brought on by a protein the iris produced that could either turn into a leaf or flower — I couldn’t help feeling the iris was speaking to me. After all these years, the protein had chosen to come into bud. I half believed my father was the iris, his essence caught up in the petals. I only wished I had I better words to explain what I was seeing.

I knelt down until I was eye-level with the bud, gazing at the delicate blue caught up in the unfolding petals. The truth was the wild iris I was staring at probably wasn’t the exact one Dad dug up in the 1960s. Wild iris typically live for twenty years, and over thirty-five years had passed since Dad dug up the original one. But they spread by way of underground rhizomes so the iris I was staring at was likely a relative of the one I found in the woods.

*

Two years before Dad was due to retire, strange things began to happen.

My nineteen-year old sister told me how, on a family vacation to Maine, our typically frugal father spoiled them, insisting that she and my younger brother book as many pricey deep sea fishing trips as they wanted and order the most expensive item on the menu while Dad, a man who loved eating, picked at his food.

He must have known something was wrong, my sister later hypothesized, hoping to make his last summer unforgettable for his two children who he’d never see graduate from college.

Then, a month later, he fell on the tennis court. He’d been on the Lederle tennis team for almost thirty years, and although he no longer took home the “Men’s Doubles” trophy, he still had a reputation for being fast. That evening, though, as he lunged forward to return a serve, his customary agility failed him. He became dizzy. The court started to spin, and he fell forward and landed on his head with such force that the other players were surprised he didn’t lose consciousness. When he finally came to rest on the court’s asphalt surface, the three other players rushed over to help him up, asking if he needed an ambulance. My dazed father sat for a while in the center of the court and kept repeating, “What happened?” Then he stood up and finished playing the match.

Not long afterward, my mother called me in Chicago. It was 1982. I was 29, and as I juggled one-year old, Sara, on my shoulder, my mom filled me in.

“Dad’s been feeling really tired lately.” My mother’s voice sounded strained and frightened. “I never told you, but last month, when Bessie and Johnny were home from college, we went to Maine, and he stayed in the cabin while everyone else went hiking. ”

The muscles in my shoulders clenched. Refusing to hike might not be strange for some people, but it was for my dad, who sometimes parked the car miles from his final destination just so he could walk a little more.

“So” my mother continued, her voice steady so as to not alarm me, “He went to see Dr. S. who thinks he has primary liver cancer, which doesn’t make sense because apparently the liver is a usually a place where cancer metastasizes to, not its starting point, so Dad’s getting a second opinion at Sloan Kettering. I hope the doctor there knows what to do.”

In the weeks that followed, my father underwent a series of tests to locate the other tumor growing in his body, but Dr. S’s initial diagnosis turned out to be correct. The only tumor was in his liver, a tumor that turned out to be exceptionally rare.

Immediately, people at Lederle started asking questions.

Why would a man in excellent health who came from long-lived people develop a rare tumor? His own mother, 89 at the time my father got sick, would survive him by four years when she finally died at age 93. Was it possible, his colleagues postulated, Dad had been exposed to some type of carcinogen in the lab?

In a matter of months, he lost forty pounds, and as his flesh melted away, the bones in his face seemed to lift out of his skin, and his trousers, when he bothered to get dressed, ballooned around his stick-like legs. One morning when I was visiting, he shuffled out of his bedroom just as I was preparing to drive him to a doctor’s appointment. He lifted up his pant cuffs to show me his grotesquely swollen ankles and feet as if some diabolical imp had taken a bicycle pump to them while he was sleeping. He couldn’t get his shoes on; he could barely walk. “What’s going on?” he asked, his dark eyes plaintive; I wanted to weep.

At first, Lederle people streamed in and out of the house. Some, family friends, brought casseroles and offered support for my mother who barely left the house in my father’s final weeks. Others arrived on official business, gathering around his bed with papers about patents or procedures for him to review and sign.

Then, there were those who wanted to save him or at least to figure out why he was dying. Several colleagues wrote letters to Lederle’s medical director asking for an inquiry. Someone else arranged for my dad’s slides to be sent to another major cancer center in another part of the country for a second opinion. One of their own was dying, but they were also nervous. I imagined them whispering among themselves: what if what is happening to John Martin happens to someone else?

I know my father thought about what might be killing him. During his final months, he tried to identify the mystery compound even though he knew it was futile. He’d handled so many unknown substances in his thirty years as a chemist. As he explained to me when I was teenager, his job was to discover new antibiotics, to identify the ingredients before him. It was also an era of lax safety standards at a time when conducting chemical experiments was more hands on.

My father did not go into that good night gently. His was not one of those “good deaths” immortalized in my mother’s ladies magazines where the family gathers around the bedside, murmuring heartfelt goodbyes in anticipation of visitations from angels or mystical tunnels. In the final weeks, he was in a lot of pain, and there were few ways we could ease it. The hospice movement was in its infancy in 1983, and palliative care was difficult to secure.

Earlier in his illness, he’d spent a night in hospital, and after an uninvited chaplain wandered into his room and offered to pray for him, he flung an empty coffee cup at the wall. So I imagine Dad would have been furious if he knew the image that kept returning to me in his final weeks was that of the crucifixion even though I wasn’t religious either. However, witnessing the mortification of my father’s flesh and psyche awakened childhood memories of a series of stained-glass windows, whose brutal images of The Stations of the Cross I used to puzzle over. Looking back, in addition to my grief and outrage, I think I was terrified. Death looked so much more difficult than I’d imagined that I wondered how I’d ever manage when my time came. At the same time, I also remember sitting by his bed, aching to take his pain into my body like food or drink, to carry it around for him if only to ease his suffering for an hour.

*

Every spring after that first time, the iris continued to bloom in my garden. Never more than one or two blossoms at a time, but on sunny days, the quality of light pouring through the petals reminded me of the flower’s fragility. Delicate flowers blooming on sturdy stalks, a cycle that I hoped would go on forever.

Then, in 2006, after the company my husband worked for in Chicago offered him a transfer to New York, he and I decided to move back east.

At first, I didn’t think about the iris. I was busy with work, graduate school, and mothering my two college-aged children. The move was months in the future although if you’d pressed me, I would have said that I planned to dig the iris up, swaddle it in damp paper towels like my mother had and take it back to the land where it had started.

Then, complications started to crop up. For one thing, Josh and I planned to rent a van in order to travel cross-country, a two-day journey. I imagined the iris jostling around on the floor of the back seat while our two terrified cats mewed in their cages. Then where would we plant it when we arrived? We planned to live in a furnished short-term rental in Manhattan for several months to give us the opportunity to go house hunting. Everything we owned would be storage. The dishes, the picture albums, and the pheasant feather my son found in Wisconsin, would survive, but an iris?

Still, right up until the last minute, I planned to bring it with us. How could I leave behind a living entity so intertwined with my father? Then, a few days before we were due to leave, I pictured my father in his lab where he’d handled so many substances. How once he developed an allergic reaction to one of them, blisters oozing over his entire body until his skin resembled the peeling bark of an ornamental tree. He eventually recovered, but for several weeks, when I arrived from school, a sightless monster greeted me from his perch on the couch. When he got up to use the bathroom, his eyes concealed behind those horrible blisters, I clandestinely trailed behind him shutting the door to the basement, so he wouldn’t fall down the stairs.

Living things require certain conditions, and even if I bequeathed my father’s iris to a gardening friend or replanted it back my mother’s yard, what were the chances of this homebody of a plant surviving another transplanting? It had already weathered two relocations, so why gamble on another? Better to leave it where it was next to the cosmos and coreopsis. That somehow the iris would radiate its presence, and its past, and be allowed to thrive.

Time passed, and every now and then, I searched for my former house on Google Street View. By that time, I’d settled into a new house in New Jersey, and the first time I pulled up an image of the Chicago house was a year or two after the new owners had moved in. The house was painted a different color, but everything growing in the front was as I’d left it. I zoomed in and out, following the camera along the foundation, past the weeping cherry, the hostas, the spirea sporting clusters of pink blossoms. I turned and investigated the side path almost up to the side door. Then, my virtual visit abruptly ended, feet before the gate that led to my father’s iris in the backyard. I could go no further. I hoped the new owners would be versed in the language of flowers.

Marilyn Martin’s work has appeared in Third Coast, Gulf Coast, Catamaran, Lake Effect, Chautauqua and elsewhere. Her essays have been cited as notables in Best American Essays 2016 and 2018. More at www.marilynmartin.com

Andy Mister’s work has been exhibited at OCHI Gallery, Ketchum, ID; Hirschl & Adler Modern, New York, NY; Turn Gallery, New York, NY; Lowell Ryan Projects, Los Angeles, CA; Commune Gallery, Tokyo, Japan; Joshua Liner Gallery, New York, NY; Morgan Lehman Gallery, New York, NY; Geoffrey Young Gallery, Great Barrington, MA; Dieu Donné, New York, NY; Sevil Dolmaci, Istanbul, TR, and elsewhere. His next solo show, I always knew it would come to this, opens in November at Rebecca Camacho Presents in San Francisco. https://www.andymister.com/