On Language, Connection, and Peculiar Literature: an Interview with Claire Donato

by LIT Fiction Editor, Jerakah Greene

THE CULT OF CLAIRE DONATO

I first met Claire Donato through Pratt Institute, where many of my friends have studied with her. Before we met in person, I had heard dozens of stories about her teaching ethics, her fascination with poetry and literature on the internet-plane, and her ghostly Victorian style. I admit that I idolized her a bit; she is the kind of literary citizen everyone should aspire to be, a fixture of the New York literary scene, with impeccable taste in film and aesthetics (she recently curated a diptych of Bonjour Tristesse and David Lynch’s Fire Walk With Me at Roxy Cinema, which, like, yeah. I don’t have to tell you how cool that is—you already know). Two years later, I can confirm that the cult of Claire Donato remains strong. With the publication of Kind Mirrors, Ugly Ghosts, a collection of short stories and one novella out now through Archway Editions, and her poetry chapbook Woebegone with Theophora Editions, the world is finally waking up to Claire’s circular genius. I had the pleasure of speaking with Claire about her new projects and influences. Welcome to the cult of Claire Donato!

JERAKAH GREENE: First, I want to say congratulations on publishing two books this year. I’ve seen you described as a longtime legend in underground literature. How does it feel to be emerging from the underground, as it were?

CLAIRE DONATO: As Jack Spicer once said, “Words make things name themselves.” While I’m totally flattered by and blushing about Archway’s description of me as “a longtime legend in underground literature,” I would never think to refer to myself in these terms. But… I’ve lived in New York City since 2009 and have therefore clocked thousands of hours on the subway (predominantly the F train and C trains). So I suppose I’ve been emerging from the underground for a very long time, but also descending. The trains are unfortunately not that reliable, and sometimes the subway stations have aboveground platforms.

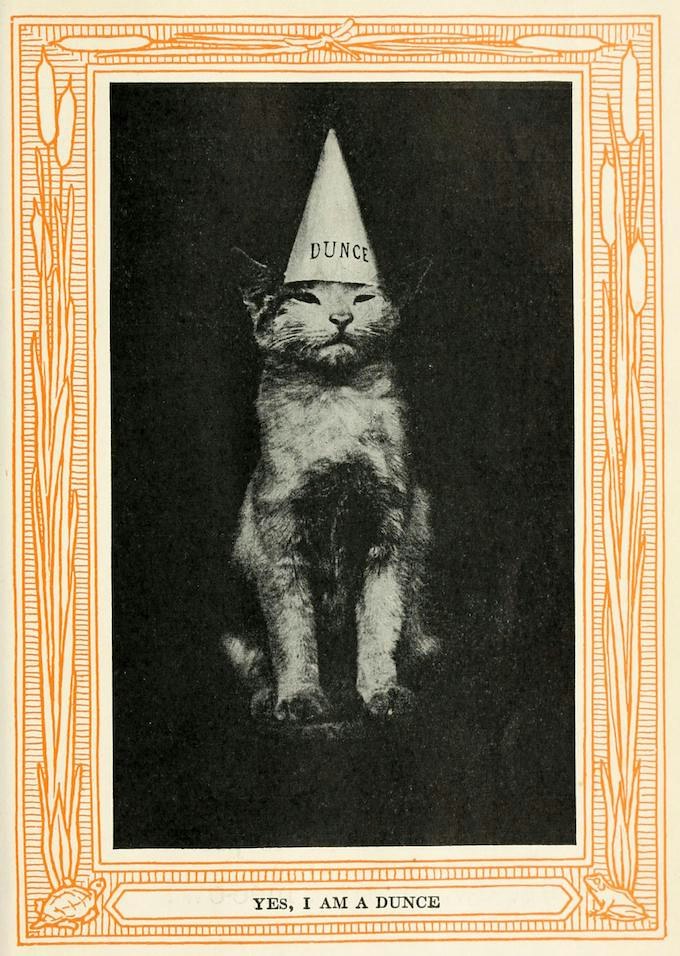

JG: Your cat, Woebegone, is a featured character in both of your new works. What is it about Woebe that you find so inspiring? How is she handling all the attention?

CD: In a Q&A at Twenty Stories Books in Providence, RI, my friend Adrian Shirk and I were talking about animal sanctuaries, and the presence of nonhuman animals in our work. Prior to the Q&A, Adrian read an excerpt from her book Heaven Is a Place on Earth: Searching for an American Utopia about Cracker Box Palace—a private animal shelter and sanctuary at Alasa Farms in Alton, NY—and I read a short story from Kind Mirrors, Ugly Ghosts called “David.” In “David,” Woebegone’s fictional likeness appears as a newly adopted kitten whom the story’s narrator has trouble gracefully integrating into her apartment, as she’s still mourning the loss of her elderly cat Brix. After adopting Woebegone, the narrator cries and cries and cries for three days straight as Woebegone “sniffs her apartment like a task.” She even sings Woebegone a welcome song through seemingly endless tears while wishing the kitten would die.

To the Twenty Stories audience, I reflected upon my narrator’s relationship to apartment: both psychic apartment—as in loneliness—and also to the physical one-bedroom apartment where “David” is set. I had not before considered that someone’s psychic and physical apartment can serve as a nonhuman animal’s sanctuary, and that this feedback loop between the nonhuman animal and the human being can be healing.

Back to Woebe, and your question. A few months ago, I had to prepare a Safety Plan for my psychiatrist. In case you’re not familiar with it, a Safety Plan is a worksheet upon which one can lean during times of personal crisis. It includes a list of warning signs a crisis may be developing, internal coping strategies (things one can do to take one’s mind off of one’s problems without contacting another person), people and social settings that provide distraction, and people whom one can ask for help. The Safety Plan worksheet ends with a prompt: THE ONE THING THAT IS MOST IMPORTANT TO ME AND WORTH LIVING FOR IS: ________________. I answered “Woebegone,” which feels sad to admit, on the one hand. On the other hand (or paw), Woebegone inspires me to stay alive in part because she doesn’t know she’s getting as much attention as she is, and yet nevertheless continues to give me energy that feels like unconditional love. And maybe the most inspiring thing is that Woebegone doesn’t even know she’s giving unconditional love, because cats don’t know about verbs such as to give or nouns such as love.

JG: KMUG is a collection of stories, each told in different conventions and forms. In “Analyst,” you explore some interesting ideas about what a novel can be (a bowl of chopped vegetables, a balloon filled with scraps of language). I’m interested in how your work in psychoanalysis, meditation, and music contribute to how you view the elasticity of the novel form. How did the form of KMUG come to you?

CD: The form of Kind Mirrors, Ugly Ghosts revealed itself over a period of about eight years. In 2016, I began to work on the novella that concludes the book, Gravity and Grace, The Chicken and the Egg, or: How to Cook Everything Vegetarian, which I thought would exist as its own standalone book. Separately from that project, I began to craft many of the short stories that constitute the first part of the collection. I called those short stories Kind Mirrors, Ugly Ghosts, and also perceived those stories as a standalone book. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I sent out the two manuscripts to literary agents. The books did not get picked up, although one agent wanted me to revise the novella as a full-length novel—to expand it by 50-100 pages—which I never did.

In 2021, my now-boyfriend Nik Slackman (who was then my good friend with whom I didn’t know I would fall in love) inquired about my works-in-progress and encouraged me to assemble a new manuscript for submission. Nik offered to help me, and via his editorial feedback, I located KMUG’s ultimate form: short stories leading into the novella, which serves as a coda. It feels worth mentioning that Nik and I met working on Mark Baumer’s posthumous collection, The One on Earth: Selected Works of Mark Baumer (Fence Books), which begins with short stories and also ends with a novella.

I think about that moment in “The Analyst” you reference in your question often, and find it delightful that Jamieson Webster called KMUG a “novel” in her blurb for the book, perhaps in homage to that story. In real life, I don’t know that I truly believe a novel can be a bowl of chopped vegetables, though I appreciate the whimsicality of the narrator’s assertion. What I do know is that my many practices—writing, music-making, psychoanalysis, personal training, etcetera—pour into one another like cups, and this fluidity informs the open-endedness of my relationship to form, to the architecture of books, and to the novel.

JG: Speaking of scraps of language—I was struck by the story “Bone Piece” and the way language becomes a living, breathing thing. All of KMUG seems to push the boundaries of language. How did you come to view language as something so alive?

CD: My mother is a French immigrant, and my father is a linguist who fluently speaks several languages, including French. French was my first language, but I stopped speaking it at home when I started elementary school, as is the case for many bilingual children of immigrants. I feel like there’s a dead first language (French) inside of me. In less melodramatic terms, it is a fractured first language for me. When I hear French—in a film, in a song, or on the street—that fractured part of me stirs, becomes animated. Feeling my first language stir is how I know language is a living, breathing thing.

JG: Your newest poetry chapbook, Woebegone, is accompanied by a video game. Where can we find the Woebegone video game? How involved were you in bringing it to life? What was that experience like?

CD:Woebegone’s Song, AKA the Woebegone video game, is forthcoming this Spring from Theaphora Editions (http://theaphora.biz). It is lovingly conceptualized and designed by one of my best friends, Anastasios (Taso) Karnazes. My involvement in bringing the game to life primarily entailed sending photographs of my apartment to Taso, which he brilliantly rendered as the game’s setting. As we prepare to launch the game, I’ll be revising a bit of its language, and I’ve also been providing feedback on drafts throughout Taso’s process of developing it.

In Woebegone’s Song, Woebegone roams my apartment, searching for bells with which to compose “Woebegone’s Song.” This is the goal of the game. The game depicts my apartment’s floor plan from an aerial perspective, where the player controls an avatar of Woebe. She scours furniture and objects for the bells while having occasional thoughts about the objects she encounters. It’s adorable and also very existential, as Woebe is trapped within my virtually rendered 1.5 bedroom apartment, like in real life. But to see Woebegone and my apartment immortalized in a video game has been a once-in-a-lifetime gift, like receiving a homemade dollhouse.

JG: Many stories in KMUG explores failed connections and the limitations of heterosexual dating, whether these connections are made via online spaces or IRL. Can you speak to this idea and why it interests you?

CD: In the context of heterosexual dating, there always exists the specter of patriarchy, which is rife with troubling power dynamics and entire histories of violences against women. As a female-identified person, I’m always shocked when I encounter brutal descriptions of ways men treat women in books, even though I’ve lived through similarly brutal experiences. For example, I’m currently reading Patrícia Melo’s The Simple Art of Killing a Woman, which is about domestic partner abuse and femicide, and I’m surprised and grateful to encounter unflinchingly grim facts on the book’s pages. It’s a brave act to write down the truth, because women are so often gaslit into not believing themselves or the truth. Lynne Tillman’s work functions on a similar wavelength to Patrícia Melo’s. A Tillman narrator might be describing a totally benign date, and then will suddenly say she was raped on the date, with no more emphasis or anything else described. I’m also compelled by dating shows like The Bachelor and FBOY Island, which in the most mainstream, banal way represent the romance myth. The genre of the heterosexual horror show comes so close to self-satire that it tricks you into thinking that women’s perspectives are running the narrative, but we are only ever looking at women being looked at and edited down, performing expectations of themselves as someone like Clayton Echard hurts them and then offers a rose.

I teach a class on the Poetics of Love at Pratt Institute, and what I’m exploring in KMUG is often love’s failure, or its failure to even germinate in heterosexual couplings. I’m not a theorist, and I’m certainly not one of my own work, but I know these subjects are very charged for me, and I’m drawn to them as a reader, which has naturally informed my writing. I tried to push the limits of my exploration of these ideas in KMUG into spaces that were even unknown to me. The book does not attempt to present easy answers or clear value judgments, but seeks to explore, describe, and understand women’s grief and disgust with heterosexuality that stems from very real troubles, from attachment to philanderers to confrontations with frightening systemic issues including rape and intimate-partner violence.

JG:KMUG has been described as Lynchian (the ultimate compliment!), which was really reinforced for me by the many different Claires that appear throughout these pages. How do you recognize these different Claires? Once on the page, do they become separate from you?

CD: Since KMUG came out, a lot of people have asked me if the book is nonfiction due to the presence of its many Claires. Alas, KMUG is a collection of fictional short stories. I opted to include multidimensional Claires and first-person narrators for a sense of coherence across the book’s landscape, in part so readers can feel like they’re with and without one character the entire time. Perhaps this desire for a semi-consistent narrator and an interlinked collection of stories links back to your question about KMUG as a novel.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about how these Claires function almost as clownlike representations of myself, wherein there exists a deep melancholy at the clown’s core. I admittedly also take a kind of perverse satisfaction in writing self-flagellating descriptions of Claire on the page, and am influenced by artists whose work imbues similar gradations of self-flagellation. Some of these artists include Jamie Stewart (Xiu Xiu), Scott McClanahan, Molly Soda, Kate Berlant, Leigh Ledare, Aparna Nancherla, Nathan Fielder, Megan Boyle… the list goes on! As someone who has been in a seven-year course of psychoanalytic treatment and is “in recovery,” it’s interesting to me that a number of these artists are sober and/or also in recovery.

JG: Many of KMUG’s influences are mentioned throughout (Sibylle Baier’s Colour Green, Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, the works of Clarice Lispector and the field of psychoanalysis). What are some other influences that may not be as obvious?

CD: I just listed a few above, and to that list would add my favorite musician Joanna Newsom, poet of harp and mind; my students; my friend and colleague Anna Moschovakis, whom I consider to be one of our greatest living American novelists; and Claudia Rankine, whose book Don’t Let Me Be Lonely changed my outlook on writing as a college senior. I am influenced by Amina Cain’s books—particularly Creature—and am inspired by Ottessa Moshfegh’s darkly humorous writing and work ethic. My former undergraduate teacher Ross Gay’s life force and love for vegetables has affected how I carry myself in the world. Anika Jade Levy and Madeline Cash’s work on Forever Magazine kept me writing during a particular summer when I did not think I could—I remain influenced by and grateful for their vision and generous support. I love Annie Baker’s plays, especially John. I love my friend Christopher Rey Pérez’s wild books Gauguin’s Notebook and Fayuca. I love walking around the Short Hills Mall in Short Hills, New Jersey. I love everything by Sophie Calle but have not visited her installation at the Green-Wood Cemetery. I love the Green-Wood Cemetery, and the Aquatic House and Orchid Collection at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. I love Hal Hartley’s movies—and Harmony Korine’s movies, Brit Marling’s movies, Kelly Reichardt’s movies. I love Emahoy Tsege-Mariam Gebru’s instrumental music (and the pieces in which she sings!), and Marisa Anderson’s too. Maya Erskine, Anna Konkle, and Sam Zvibleman’s PEN15 beautifully invokes so many emotional registers, and so does Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi’s Reservation Dogs. And I would be remiss not to mention that my formal undergraduate and graduate training was in poetry, and to my heart I hold many poets close: Rosmarie Waldrop, Alejandra Pizarnik, Chelsey Minnis, Lorine Niedecker, Lisa Robertson, Raul Zurita, Tan Lin, Inger Christensen, Juliana Spahr, Andrea Brady, my late teacher Keith Waldrop, and my late thesis advisor C.D. Wright. I am undoubtedly omitting too many other influences to count.

JG: As a hybrid writer, I am always torn between writing in my style and writing what is “publishable.” Have you experienced similar hesitation? What advice do you have for writers who are afraid they write too weird for the establishment?

CD: I began publishing 20 years ago, and have experienced hesitation and doubt along the way, as well as feelings of being too weird for the establishment. These feelings come and go, but were especially strong when I attended a graduate program—Brown’s MFA Literary Arts Program circa 2009—that had a reputation of being experimental. That word—experimental—was frequently applied to my writing by family members, friends, and some readers. I felt really trapped by it. The image of a hollow chocolate Easter bunny comes to mind.

I experienced feelings of insecurity coming up again when I sent KMUG out for publication consideration and it got rejected by publishers. As a writer, I try to keep my critical inner monologue in check and possess a pretty strong backbone when it comes to rejection—I actually think rejection can be clarifying, motivating, and a source of protection—but it was also painful to feel like I spent years creating something that was being told no. In those moments of self-doubt, it helped to have other people in my world who believed in my writing. I would often repeat their words of affirmation to myself. It also helped to have other writing projects afloat and other practices altogether: psychoanalysis, acupuncture, personal training, music-making, painting.

Over the years, I’ve been fortunate to deeply connect with other writers whose work is also peculiar, and to find spaces to publish alongside those writers. I’m thinking of the now-defunct HTMLGiant and Fanzine, both of whichmy friend Blake Butler helped edit, and also magazines like Octopus and Fonograf. One recommendation I might offer to weird writers is to find and befriend fellow weird writers, and to support them and let themselves be supported. I think it’s important to do this while remaining open to all sorts of other connections, and not letting one’s soul be corroded by negative thinking.

It’s hard to feel different in a culture obsessed with sameness. As a human being and an artist, I always try to hold in mind that I can only be who I am. And anyway, weird is a word etymologically connected with destiny, originally meaning “having the power to control destiny.” I don’t want to be who I’m not. I just want to cast spells.

Claire Donato is the author of three books, most recently Kind Mirrors, Ugly Ghosts (Archway Editions, 2023). Recent writing has appeared in Parapraxis, Forever, The Brooklyn Rail, Fence, The End, The Chicago Review, and GoldFlakePaint. She also contributed an introduction to The One on Earth: Selected Works of Mark Baumer (Fence Books). In addition to writing books, Claire makes music, illustrates, and has a 35mm photography practice. Currently, she works as Acting Chairperson of Writing at Pratt Institute, where she received the 2020-2021 Distinguished Teacher Award. She lives in Brooklyn with her cat Woebegone.