Pocket God

by T.J. Martinson

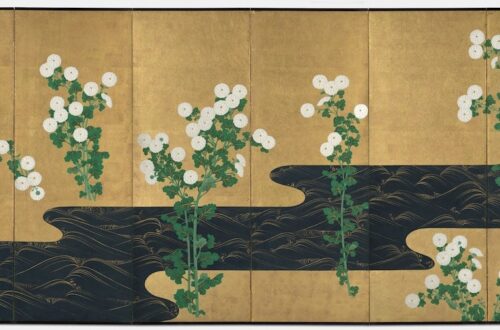

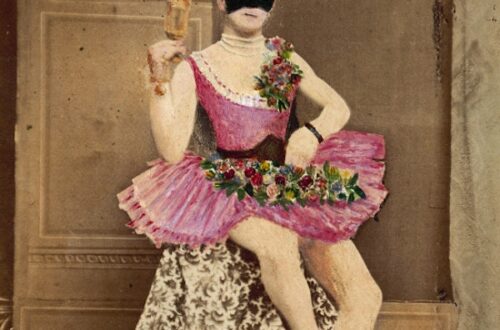

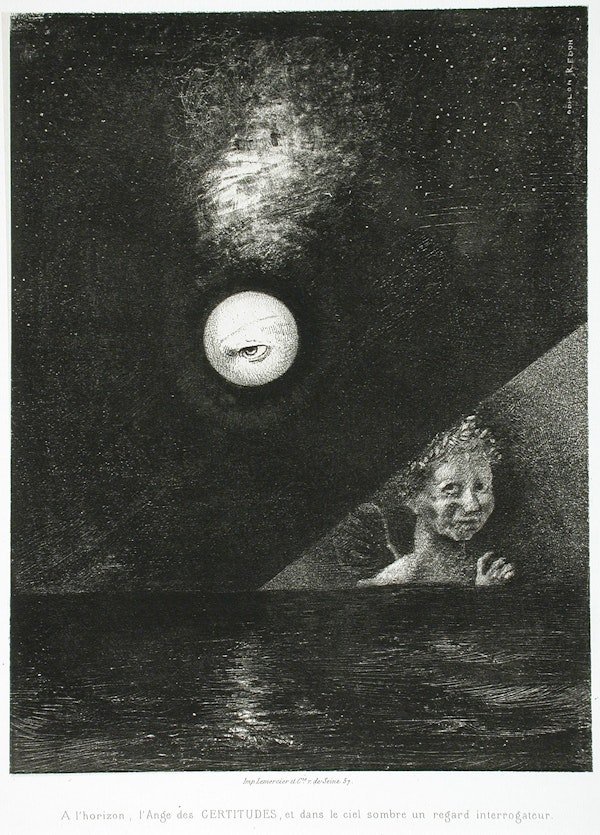

art by Odilon Redon, 1882

Your Pocket God stopped eating last week. For the first few days, it was easy enough to excuse the way it pushed away each offering of raisins like a fussy toddler, but now, eight days later, excuses are hard to come by. Still you try.

“It’s probably just a spiritual fast,” you tell your dad during breakfast as you anxiously hold your starving, gaunt Pocket God, watching it turn over weakly in your palm.

You hope your father will agree that there’s nothing to worry about, but your father makes a concerted effort at pretending not to hear you, taking sudden and intense interest in an off-balanced table leg. He could care less about your Pocket God. He’s said as much several times, the latest of which was during the road trip to Colorado. From the backseat of the Camry, you excitedly told your parents that your Pocket God had made the final evolution from demi god to full-on god, a transformation accompanied by a digital rendition of Handel’s “Messiah” playing from your Pocket God’s mouth. Your dad smacked the steering wheel. “For god’s sakes, put that thing away and look at the mountains.” Your mother told him not to yell, but you know that even she finds Pocket Gods to be a dumb fad, an inarguable indication of your generation’s moral and intellectual decay. Her exact word was sacrilegious, but what she does not understand—no matter how many times you’ve explained it—is that your Pocket God isn’t making fun of any other god or any religion. Like the commercials say, it’s simply a handheld god that you can dress and love and feed and, if you so desire, pray to.

If anything, it’s the opposite of sacrilegious. It’s super religious. You’ve never been so religious in your life. You pray to your Pocket God each morning, while you’re waiting for the bus to and from school, and before bed each night. The morning prayers are the same—Please help today be better than yesterday. To the point. No mincing words, no prevaricating praise, no manipulative self-flagellation—just the truth. And up until last week, around the same time that it began what you hoped to be its fast, your Pocket God would respond to each prayer with a thoughtful “okay” or sometimes just a little chirp, the sound that a gas station door makes when you enter it, as if saying it sees you and it’s happy you’re there.

##

And now this morning, just before breakfast, you could not rouse your Pocket God from its sleep. You did not even know it could sleep. Normally, it sits on your bedstand with its eyes wide open omnisciently. But this morning, its eyes were closed, and it was lying face down next to the alarm clock. Your Pocket God’s once-radiant skin now the color of a gym sock. You might have panicked if you hadn’t noticed that it was breathing, evidenced by the teensiest ripples of its robe draped like a tissue over its sharp rib cage.

It didn’t wake up until you begged, tears forming in your eyes, and even then, it woke just long enough to go back to sleep with a teensy huff, the way a flower might breathe in October.

At breakfast, your father continues to ignore you and you break into hysterics. You present your sickly Pocket God to your mother as she enters the room, pleading for answers to what you fear to be an unanswerable question. “What do I do?” you cry.

Your father says he isn’t getting you a new one. Your mother pours a saucer of milk and sets it in front of your Pocket God, as if it were a stray kitten.

“It eats raisins, not milk,” you explain, unable to control your voice.

She tells you not to talk to her like that; she says she’s only trying to help. Your father clicks his tongue and says they never should have gotten you the goddamned toy to begin with.

You scream that it’s not a toy; it’s a god!

Your mother says if you don’t start watching how you talk, they’ll take your Pocket God away for a week. You can’t risk it—your Pocket God requires your care—so you fall back into your chair and spoon cereal into your mouth without tasting. You can’t help but wonder if your parents know something you don’t. If they suspect that you’re the problem, and the only cure for your Pocket God is less of you.

When your mother isn’t looking, you push the bowl of milk closer to your Pocket God. Just in case. Your Pocket God crawls across the table, passing the bowl, and throws itself from the ledge, landing on the tile with the faintest of whimpers.

##

Before first period, you drag Harvey to your locker to show him your ailing Pocket God. At the private school down the street, they get to carry their Pocket Gods around with them all day, but here at the public school it’s not allowed. It’s bullshit, Harvey says every time he gets caught sneaking a Pocket God to recess, because America has laws and freedom and laws for freedom. When he challenges the teachers like this, they get antsy, especially when Harvey starts talking about the freedom of religion. That’s usually when they’ll acquiesce, letting Harvey push his Pocket God down the slide over and over again, both of them lost in their delight of each other.

Harvey actually owns two Pocket Gods, because his parents are divorced and rich enough that they get their cars washed at least once a week, but probably more. When they pick up Harvey from school, even on a cloudy day, their cars glow. Harvey told you a few days ago that he’s going to get a third and fourth Pocket God for his birthday. “A whole pantheon,” he said, using a word he learned in your English class and hasn’t stopped using since.

If anyone will know what to do about your Pocket God, it’s Harvey. He spends a minute looking it over, lowering his glasses to the tip of his nose like doctors do on television.

His face grows grim and grimmer still as he pokes your Pocket God’s caved stomach. “You said this has been going on since last week?” Harvey asks.

“Friday,” you reply. “Maybe Thursday.”

“What kind of raisins are you feeding it?”

“Same that you feed yours.”

“The red box with the girl on front?”

“Yeah, that kind.”

“Hm,” Harvey nods. “That’s a good raisin.”

Harvey has always seemed older, wiser, and generally better than you and everyone else in your grade. He was the first person you heard openly discuss masturbation, which he described as a genie’s lamp with infinite wishes. He bought a vape from China on the internet and learned to smoke it so that the smoke came out his nose like a dragon or Harvey’s older brother Seth. Harvey is even dating a girl from the private school who gets to carry her Pocket God with her to every class. Harvey said that his girlfriend gets to pray to her Pocket God whenever she wants, even during the pledge of allegiance.

Sometimes it doesn’t even feel like you and Harvey live in the same world. To him, the world is a genie’s lamp—no, that’s gross, it’s more like a book he reads and comprehends at will. But to you it is a sick Pocket God, a mystery that requires people like Harvey’s help to understand, so it terrifies you to see that even Harvey does not know what to do about your Pocket God. It barely moves when Harvey holds it to his ear to see if it’s speaking, pleading, dying, whispering, begging, condemning, granting, prophesying, or damning.

Nothing.

“Wait here,” Harvey says before running down the hallway to his locker. He returns with one of his own Pocket Gods. The first one he ever got. Harvey named it Great Lomax. Great Lomax turned full-on god long before yours and shines even brighter than Harvey’s mom’s Mercedes. It stands on Harvey’s palm, its muscular arms held behind its back like a soldier awaiting orders. “Great Lomax,” Harvey says, placing his Pocket God next to yours in the locker, “can you tell us what’s wrong with my friend’s Pocket God?”

You watch in equal parts horror and awe and envy and guilt as Great Lomax kneels down, the ropey muscles in his thighs pressed against his skin like hieroglyphs, and reaches an outstretched hand to your weary Pocket God’s shoulder. Seeing the two Pocket Gods next to each other, whispering to one another, makes you even more worried than you were before. Great Lomax makes your Pocket God look like a shriveled stick of string cheese that has decided to rot away. As Great Lomax performs his examination, you nervously eye the hallway clock. Two minutes before first period. The thought of spending the entire day locked in this state of unknowing worry, trapped behind a desk while your Pocket God starves and decays, makes you want to hurl up this morning’s Cheerios. But maybe, if you did, you would be sent home. Maybe that’s what your Pocket God needs. You would dote on your Pocket God the same way your mother would dote on you. Grilled cheese and tomato soup for you, piles of raisins for your Pocket God. A few episodes of The Price is Right in the morning, some re-runs of Family Feud in the afternoon. Maybe that’s what your Pocket God needs—a day off. No prayers, no expectations. Just rest.

When you got your Pocket God, you hadn’t imagined nursing it to health, but you would do it just the same, you would do it happily, if it meant today would be better than yesterday.

##

You got your Pocket God for Christmas. You knew it was coming, because you heard your parents fretting about it through the vent in the wall. Your father said it was expensive, your mother said it was sacrilegious, but you heard in their voices the bored resignation mixed with perfunctory worry, as if they were begrudgingly reciting lines for Concerned Parents One and Two. So, when you finally unwrapped your Pocket God on Christmas morning, you really hammed up your joy. You squealed in an octave you’d been rehearsing. You hugged your Pocket God even though it felt like a stupidly childish thing to do, and you held the pose long enough for your mother to take a picture that she could send to her friends. The reaction was a lot, but the feelings were real. The joy was a radiating warmth that started in your stomach and branched into your fingers. It felt just like the commercials promised—the universe in the palm of your hand.

Your father found some batteries in the drawer next to the sink and helped you put them in. That’s when your Pocket God’s eyes first opened. It looked down at its hands, flexing its fingers, and then looked down at your hand, the much larger hand that held it, and then back at its tiny hand. It went back and forth like that for quite a while before noticing you. Your enormous eyes trained on its own.

“What is this?” it stammered.

It was the only question you weren’t ready for. You’d expected something like, “What’s your name?” or “What can I do for you?”

Your father and mother unwrapped each other’s gifts—a box-set of Seinfeld and a bracelet, respectively. You interrupted them to ask how you should respond.

“Just tell it your name,” your mom suggested, holding her new bracelet to the light with the big fake smile that she typically reserved for Harvey’s mom when she dropped Harvey off to play.

“It didn’t ask my name. It asked What is this?”

“What is this?” your Pocket God repeated, taking in the living room, the Christmas tree, the wrapped paper strewn like wreckage. “What is going on?”

“Two-hundred dollars,” your father sighed, getting up to refill his coffee. “The thing doesn’t even know what’s going on.”

“Who said that?” your Pocket God leapt back, nearly falling from your palm, but you caught it with your other hand.

“That was my dad.”

“Where am I?”

“My house.”

“Who are you?”

You told him, but you felt self-conscious with your mother listening now. It felt less like talking with a Pocket God and more like introducing yourself to Daniel, the son of your mother’s college friend, who wore a karate gi and broke your Nintendo because he sucked at Mario Kart even though you were trying to take it easy on him. You think I don’t know what you’re doing? I don’t need your charity! Daniel shouted before kicking the Nintendo across the room with the power and precision of a yellow belt.

Your Pocket God looked as unimpressed with you as did Daniel, but far less likely to attack. If anything, it looked afraid that you would attack it, as if you might close your fingers around its body and squeeze until its godly juices dripped from your fingers.

“Why am I here?” your Pocket God asked.

After your parents cleared out of the living room—mom tending to the crockpot and dad taking a call from grandma—you offered your Pocket God an answer in the form of your first prayer. When you finished, it said, “I don’t know if I can do that.” But it was just a demigod back then, not nearly as powerful as a full-on god, so you were content to just feed it raisins and watch it eat until it asked you to please just go to bed and give it some privacy.

##

Maybe had you named it, you think as you watch Great Lomax take your Pocket God’s pulse, it would be fine. But naming it hadn’t felt right, not to mention you couldn’t think of a name suitable for a god that wasn’t the name of a god already, and the last thing you wanted to do was offend your Pocket God with something ludicrous like Great Lomax, even though Great Lomax seemed to have taken nicely to the name. When Harvey first brought him to school, his Pocket God had introduced himself to you from inside the locker. “I am Great Lomax,” he had said, proudly puffing out his chest, “and I am Harvey McCullen’s Pocket God! It is a pleasure to meet a friend of Harvey’s.”

After a lengthy inspection of your Pocket God, Great Lomax stands up and whispers in Harvey’s ear. Harvey nods along at irregular beats, “Mhm, yeah, okay.”

You wait, watching your Pocket God roll further into your locker, curling its knees to its chest.

“What did he say?” you ask Harvey once Great Lomax has finished delivering his prognosis.

Harvey doesn’t answer right away. Great Lomax touches his arm, a gesture you interpret as comfort, a reminder that it is there with him. “He said you need a new Pocket God.”

“Is mine broken?”

Harvey again looks at Great Lomax, who makes a gesture that you can’t possibly interpret, but Harvey seems to understand it. “Sort of.”

“Isn’t there something I can do?”

“I am afraid not,” Great Lomax says, climbing down Harvey’s arm and into his pocket. “Some of us, we aren’t up to the task. It’s no one’s fault.”

Harvey hurries off before the bell rings for first period. You linger about, just long enough to drop some raisins around your Pocket God in case it gets its appetite back, in case it gets better.

##

But it doesn’t get better. You check on it throughout the day between classes, but your Pocket God is dying. There’s no other word for it because there’s no other explanation. Its skin paling and graying and flaking, each passing hour compressing its body further and further into itself until, by the final bell, your Pocket God could be mistaken for an old hamburger wrapper you’d left in your locker and forgotten.

You place it gently in your pocket like the many times before, but this time there’s no movement—no struggling or discomfort or tiny elbows pressing against your legs. Just an unbreathing lump. Your father will say you broke it. Your mother will act sad and say that everything dies. You’re not sure which is worse. You’re not sure which you wish is true.

Outside, you see Harvey run to his dad’s Camaro, and you shield your eyes against the sun’s reflection on the hood. Through your fingers and the Turtle-Wax glow, you’re pretty sure you see Harvey watching you as the car pulls away. He’s the first kid you’ve ever seen look truly sorry for someone. At this rate, he’ll be the first person you know who won’t need to watch his Pocket God die, and you wonder why the world doesn’t try to hide its affections and indifferences.

To some, it offers a pantheon; to others, a sewer drain next to the bus stop.

You kneel next to the sewer drain, and you know what to do. You wish it was harder to do it. You wish you could cry. You wish there was something to deliberate, a question worth asking, a riddle in need of solving. You wish it felt even a little bit cruel to drop your Pocket God inside the sewer drain without even listening for a splash. You wish for several things at once, like two-hundred dollars, the wisdom to have tried new batteries, a Christmas in February, but today was worse than yesterday and you’re tired of wishing otherwise.

T.J. Martinson is an assistant professor of English at Murray State University. He is the author of The Reign of the Kingfisher (Flatiron Books) and Her New Eyes (Clash Books). His shorter work has appeared in [PANK], JMWW, Permafrost Magazine, Pithead Chapel, Heavy Feather Review, and others.