Regions of Identity by Jeri Griffith

She is me, twenty-two years old, young, younger than I can imagine being from this vantage point. She’s driving a car down a narrow road, wending her way through the New Hampshire woods. That girl is trying to master a stick shift for the first time. She’s not doing too badly, but on inclines, when the gears don’t catch, she finds herself rolling backwards and gets a sick feeling in the pit of her stomach.

My former self is newly married. She blasts the car radio, making pop songs into a soundtrack for her life. Rock me gently. Rock me slowly. She talks to herself. As usual, she’s journaling in her mind, trying to tell someone, anyone really, about what is happening to her.

Most days, during any spare moment, filled with longing, she meanders woodland paths. She’s not even sure what she longs for. If it rains, she dons an orange plastic poncho so she can walk through drizzle without getting wet while brushing away the ubiquitous mosquitoes that buzz around her ears.

Falling droplets of water cause the whole forest to move. The leafed trees quiver and speak. Who can tell what they are saying? The forest is a mat, a living substance with processes involving soil, water, root, and limb. Moisture slithers downward through the needles of the white pines, down and down to seep into soil, to be recovered by roots where it fuels the trees’ upward push toward the sky. She intuits this and it feels comforting.

As it is, they will probably leave their job here at the end of the summer. She likes living in these mountains and forests, but the job itself is tough. At this summer camp and boarding school for kids with special needs, there’s a shortage of house-parents and teachers. She and her husband aren’t really trained to work in this kind of environment. Still, she might choose to stay on because she’s fallen in love with this bucolic, rural place.

Where will they go next? She has no idea. They have just graduated from college. They’ve left the campus with its red brick buildings and maple trees. There, they read Melville and Faulkner. He is planning to write. She wants to paint. These things animate them. They hope to find a way.

She perseverates. Over and over again, she says the word Saskatchewan. Maybe we could go there, she thinks. How would I be in Saskatchewan? In Saskatchewan, maybe I would be different. I would make paintings of the prairie, the wheat fields, and the wide sky. Always, there would be a storm coming in or going. In Saskatchewan, it would be best to work in watercolor. She’d take in the sweep of the wide, open country and let it flow across the page. At night, it would be very, very dark with only the fixed points of stars to light the way. She thinks about Saskatchewan. Meanwhile, her world continues to crack open. It blooms white light, monthly menstrual blood, and blue water.

Often, strong feelings overwhelm her—feelings she can’t always name, identify, or even claim as her own. Sometimes she is euphoric, almost high on life, but she also knows that beneath any happiness there lurks a deep sadness that can border on despair. She swings hopefully from the darker side of the feeling arc toward something that, later, she might even call ecstasy. The shimmering reality of the visible can leave her speechless. It is excruciatingly joyous, even painful to be alive. Her perceptions of the world around her are acute and very sharp. She can look at a gravel drive and see every individual stone, each with its own history and voice.

But this is not something she can talk about. She wants to, and sometimes she tries, but there are only brief moments when that poetry is allowed to surface. Most people are busy with their day-to-day concerns. They don’t want to be like her. They don’t want to dissolve into outer space. She learns to bear the heat of a brightly burning, constant fire. The point is to contain the flame and channel the energy. Sometimes, that’s difficult. She longs for the patience of a stone, for the silence that exists underneath the sidewalks, below the pavement where worms make

their quiet way past boulders through the sediment of soil. Imagining that kind of place helps to quiet her mind.

Six months later, she sits at a kitchen table drinking a cup of tea in the Kansas City apartment where she and Jon are living. The windowsill is always dirty. Particles of soot and dust blow and lift sky high only to settle as black specks marring perfection. She sits there looking out that window at nothing and nowhere. She isn’t even sure what to look for. She feels depressed.

The girl wending her way through the forest was familiar with meandering woodland paths. She had a vision, a way of seeing that nourished her. The trees spoke to her in their own language. Clear flowing rivers were metaphors for her life, and the land itself stretched out freely in all directions. But none of this has anything to do with survival in the city. It takes more than mere euphoria to live amongst so many other people.

II.

Five years later. I am still her, but I’ve changed.

We have, once again, moved back to Kansas City after a stint teaching at a boarding school in rural Iowa. We’ve come here for job opportunities and to be close to Jon’s family. I’m not all that happy about the move. I long for some open space where a sylvan grove of trees thrives. I see them in my mind’s eye, ghostly and insubstantial in light refracted by morning mist, standing tall and together. The trees represent a peaceful state of mind. In my imagination, I reach them and shelter beneath them. In the real world, I am here.

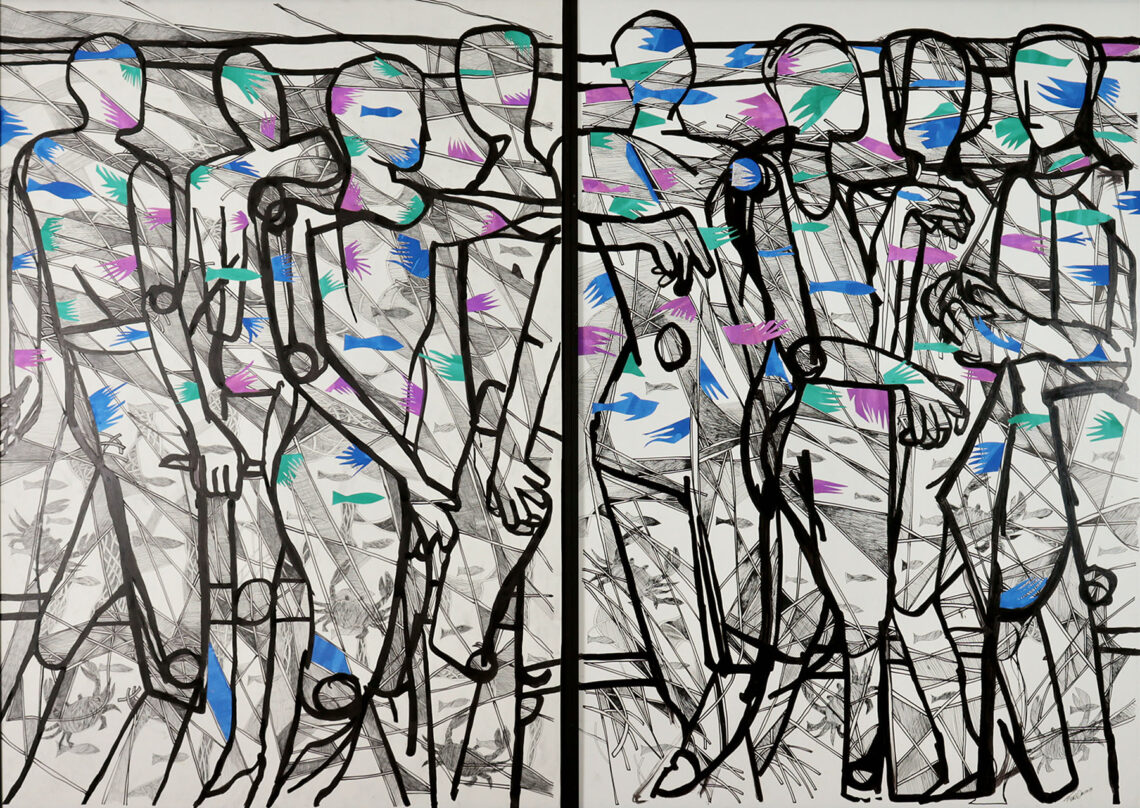

But I’m not sure I want to be here. The truth is, I think I might hate it here. I have always found refuge by being alone in nature. Here, my feet constantly touch pavement. As I wait patiently at bus stops and push my way through street crowds, I know enough to avoid eye contact. A gaze could make me vulnerable. It isn’t safe to issue an invitation to a stranger. Men and women glimpse one another in quick glances, and the seeing is like a jolt of electrical

current.

I ride this bus three times a week. As I stare through the window at storefronts flowing by, I enter a dreamlike state. It is my defense—the place I go to when overwhelmed by the passing collage of images and signs my brain doesn’t even have time to process. I am trying to protect myself, attempting to build a wall that will separate me from what is out there. I often hum softly while I ride. Sometimes, I say words over and over. The 23rd Psalm. Surely goodness and mercy will follow me all the days of my life. Surely.

Every day is an effort to find my way through a labyrinth. I struggle to follow corridors of movement from one place to another and trace the lines of public transportation past numbered streets. While swallows arc through the air between buildings inhaling invisible insects, pink-toed pigeon squabble as they crop remains from discarded fast-food containers. There’s trash everywhere.

This is 1980. I work for an arts organization downtown—a regional arm of the National Endowment for the Arts. I am young and not doing anything terribly important there. Mine is an office job. I pack posters for our touring visual art exhibits, type letters to potential sponsors of dance events, and help prepare brochures that might generate audiences for symphony and theatre. I take the bus from our apartment to and from the office.

My bus stop is at 54th Street and Troost Avenue. It’s only two blocks from our place on Harrison Street. My house key, kept on a chain in my pocket, allows entry into the locked, enclosed space where I spend the night with my human and animal family—Jon, a chocolate lab called Thea, and a gray tabby cat whom we named Ishmael, after the protagonist in Moby Dick.

We kiss, and then share fragrant, herbed chicken and potatoes from the slow-cooking pot. Gradually some poetry of motion and aroma replaces my mental pictures of storefronts and traffic, and I no longer feel I’m someone acting as an extra in an epic cinematic film. Here, the world is reduced to this white bowl in the kitchen light, and we slide into the day’s fatigue at our small table for two. We don’t own a television. After supper we walk the dog, read books, and make love. That is our life. That is my life at this time.

What am I called to do here? I have no idea. I live and breathe each moment as if it were

my last. Never have I felt this close to suicide. Never have I felt it did not matter if I lived or

died. Each day, I sink like a stone.

The Missouri River is wide, deep and brown with farmland silt. It enters town from the north, as does the interstate highway 35 that edges miles of railroad yard and track. This is the hub in the middle of our country. The trains carry steaks and grain, even Quaker Oats. The rhythm of the railway tracks is both visual and aural. It crawls, sounds, traverses, plays outward—to the north, south, east, and west.

This is the heart of the heart of the country, south of the Great Lakes, north of New Orleans, but my heart is not here. I’m not really sure who I am in this place. And I don’t understand how to survive all this pain. The assault of the city is relentless. Every day, I am worn out and used up, and so fearful that I do not, cannot even care what happens to me. In response, I make art. I create papier-mâché sculptures. My praying white figures bend in on themselves and are attached to wooden stretcher frames. They are imprisoned, secured to rectangles, and unable to move. Their bondage reflects my own state of mind. My sculptures pray for freedom. I myself long for the flow of a cleaner river, my body under water, my body in water.

I am without reference points, at sea so to speak. This time is like an illness. But let’s say that none of this is bad. Let’s say that nothing is wrong, that everything is right. Let’s say that spiritual growth requires some element of suffering. Some things I really feel called to do—to love certain people unconditionally, to make art, to cook dinner, to walk the dog. I’ve never had in mind the house or the car I wanted to own. I haven’t imagined the faces of my children or how I would dress them in brightly colored athletic outfits. I have no idea what the future might hold.

And even if I feel like I’m dying, life erupts around me like a volcano. Whole tracts of the city are in the process of being torn down and rebuilt. I pass the wreckage and salvage pits on my way to work. Early in the morning, the bent figure of a man stoops and warms his hands over the fire in a trash barrel. Tongues of flame shoot upward toward the sky, reddening the mist that gathers in the hollow places. The man is always there even before it is really light out.

Does he emerge, like some animal sensing the dawn—driven by hunger and need, seeking warmth that the sun will not provide because it is nearly winter, and the days are not warm? I don’t know. I only see him as I pass by on the bus. In fog, he looms—a faceless phantom haunting that moonscape. There, he shoves another board into the small fire that is his life among the heaps of broken bricks and plaster in that place where old buildings are being

taken down to be replaced by new ones.

Each day, wrecking balls strike edifices cited for destruction, exposing more of their once-hidden rooms to dampening air. One lavender-colored wall is revealed beside a yellow kitchen. Above some careening floor, a bare light bulb suspended from the half-destroyed ceiling is no longer connected to any power. Seemingly ad hoc crews work the rubble, foraging whole bricks from the dust that rains down, stacking boards into piles, and taking anything that might be sold before the rest is hauled away in dump trucks.

Somehow, the old man is part of the process. Perhaps he has always lived here in this neighborhood. Once fine apartments, these former dwellings lined a Kansas City street where radios jived with jazz. People sitting on open porches to escape the summer heat regaled one another, and young folks paraded finery and first cars. Now all that is gone, and this man is alone, warming himself next to the improvised stove. I identify with him. Like me, he seems a lonely sojourner in a world that is being torn apart and rebuilt. What thoughts are in his head? Who does he talk with under his breath?

The bus ride continues. Reality has become a series of disconnected and fleeting images that last only a few seconds. The flow is broken by the shapes, the square windows that reveal other squares—a series of cubes, buildings with open and closing doors, facades that yield little. Each brief, shining, and excruciating moment comes to me as if from behind a pane of glass.

Another day. The man I’ve come to know by sight is there again warming himself beside the fire in the barrel. I observe him from the window of the bus. He does not know that I look for him. Tomorrow, he may be gone. I may never see him again and will never know what happened to him.

My identification with the old man makes me acutely aware of inhabiting a body that takes me through time and space, a body that is the same as the bodies of those around me. We are all passing through. We are burning, and it is good to burn sometimes, and to understand the nature of your own smoke dissipating. I feel the wind talking tunnels in between the buildings as it searches for the liberty of open space. Clouds shift in aimless succession across a gray sky that promises snow.

Somehow, I survive. I know that I will go on. It is not so much an exercise of will as a letting go. I imagine myself floating on the back of that great big muddy Missouri river. I am buoyant. I remain on the surface. I don’t drown. It’s not exactly a form of happiness but it has the potential to become that.

III.

Thirty years later. We’ve made several moves to different parts of the country following a trail of job opportunities. Seventeen years in Austin, Texas taught me to appreciate the Great Plains and the Texas Hill Country where clear streams percolate over limestone. I learned the names of new plants—ocotillo, mountain laurel, agave, prickly pear, and bull nettle. I watched armadillos scuttle through the brush. In spring, I would rush outside when I heard the cries of the sandhill cranes migrating north. In a way, Texas was my Saskatchewan—a whole different way of being with new foods and a different cast to people’s characters. The colors of Mexico crept into my paintings. My art became more and more figurative.

After Texas, we moved east to live in a suburb north of Boston. From there I finally mastered city life. I came to love art museums and other amenities the city offered—cultural events, restaurants, and even sports teams. Opportunities arose for me to visit some of the great urban centers of the world—New York, London, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Montevideo, Singapore. I learned my way around.

At the moment, I’m sitting alone at a table in a café savoring a cup of coffee laced with cream and sugar. The coffee is rich and dark. Boston offers the anonymity of all large urban spaces. I can observe without being observed. The man at a table across the way wears a blue baseball cap. He’s nodding his head as if to agree with his companions. I can’t hear what he is saying, but it doesn’t seem all that serious. His facial expression is somewhere between

thoughtful and silly. He might be smirking a little, but not in a malicious way, not leering, just looking at his two friends, turning from one to the other, sometimes smiling and talking quite naturally while sipping his drink.

Momentarily, a gulf opens between us, a space as wide as an ocean. It’s as if I could never know him—as if one person could never be known to another. He might as well be the old man I used to observe in the salvage pits.

Outside the café’s window, a small but verdant garden, lush with spring, drips rain. Across the street, a gray stone building thrusts upward into a light gray sky. I see a line of figures, human beings like myself, marching down the sidewalk in light fog. They’re ghostly and insubstantial. The sight of them alarms me. Each seems about to disappear like a puff of smoke. I rise from my chair unsettled and bewildered. It’s that old feeling—as if I’m somehow outside my body and behind a pane of glass. But as I walk down the street, I repossess myself. I know where I am going. I take the commuter train for home.

IV.

When Jon and I finally revisit the old neighborhood in Kansas City, we snap pictures of the duplex where we rented the first floor. It’s in better repair than when we lived there. It’s odd to be looking into the windows rather than out of them. Both Thea, our dog, and Ishmael, our cat, are gone. Thea lived for thirteen years, then got leukemia. Ishmael survived until he was twenty and had many cat adventures. At the end, he was completely blind. We would carry him into his Austin, Texas yard to enjoy the sunshine, then set a timer to remind us to go and get him because he was incapable of finding his way back to the door.

We walk together down Troost Avenue, not holding hands but aware of one another, of our bodies that have aged, of all the experiences that intervened between that time and this present moment. Some things are still the same—the Troostwood Garage where we used to have our car serviced and repaired is still there. The bus line I rode still runs regularly. We watch the bus arrive and depart with passengers getting on and off. Small charismatic churches are taking over storefronts in the area. That’s a new phenomenon. But when we veer onto the old streets we once knew, much is the same. The houses and even the plantings and the trees are all familiar.

Nostalgia is something hard to define. I do not long for the girl I was in that New Hampshire woods. I don’t wish to return to that state of narcissism and fear. It’s no longer painful for me to recall the dislocation I experienced as I tried to adapt here. I had to grow and I did grow. I’m glad to have known it all. But passing through, as we are passing through now—there’s a sadness, an intensification of life, of what life is like and what it’s about, a human

quality that infuses situations and makes them both workable and unworkable.

Our red rental car is parked in front of our old place. We finish our walk. The day’s heat is rising, as it always does, as it did when we lived here. I slide onto the black vinyl seat. We’ll set the GPS now and the voice will take us where we need to go next. Turn right at the end of the road. We do. And I wonder. My regions of identity are as elusive as a dragonfly’s shadow. Our human world is oddly made. We are mostly strangers to one another and even to ourselves. The old man in the salvage pits and the man in the café merge into a single enigma. And what of me? What am I really like? Who am I? That’s a complicated question and one I’m certain I will never answer.

Jeri Griffith is both writer and artist. She regularly publishes essays and short stories in literary quarterlies. Many of these can be accessed through her website and read online. Her artwork—paintings, drawings, and films—can also be viewed on her website: www.jerigriffith.com. Jeri lives and works in Brattleboro, Vermont with her longtime collaborator and husband Jonathan, her best friend Nancy, and two beagles, Rusty and Molly.

Jeri Griffith is both writer and artist. She regularly publishes essays and short stories in literary quarterlies. Many of these can be accessed through her website and read online. Her artwork—paintings, drawings, and films—can also be viewed on her website: www.jerigriffith.com. Jeri lives and works in Brattleboro, Vermont with her longtime collaborator and husband Jonathan, her best friend Nancy, and two beagles, Rusty and Molly.