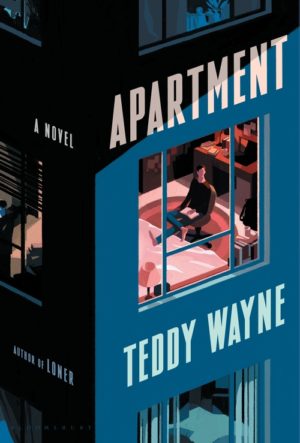

“Apartment by Teddy Wayne” Reviewed by LaVonne Roberts

Apartment is Teddy Wayne’s fourth novel and an easy read in just over 200 pages. Wayne’s novel gets to the crux of every writer’s angst in an MFA program: when you strip away the art of craft, is your writing any more interesting than yourself? Offering a rare glimpse of what happens in a workshop and the sheltered creative writer’s MFA community, Apartment speaks to what a privileged, highly-competitive MFA degree does or does not do for a writer. Moreover, it speaks to male identity in relation to male friendship.

Set in 1996, pre-popularized internet, the view from the unnamed narrator’s two-bedroom rent-stabilized apartment extends beyond Stuyvesant Town into Manhattan to explore geographical, gendered, political, and sexual boundaries in a literary world where intellectualism is currency.

The introverted narrator has been subletting from his great aunt, who’s living in New Jersey, while he was at college at NYU and then Columbia. Wayne’s narrator, a wannabe novelist, sets up his narrative when he reveals, “I didn’t mention how cheap my rent was, nor that it was an embarrassment of square footage, nor that my father, encouraged that I was taking a foal’s first shaky steps toward My Gainfully Employed Future by attending Columbia, had generously offered to pay not only the tuition but also my rent and living expenses for the two years I was in school, a stimulus package I accepted with more guilt than I had as an undergraduate.”

At the narrator’s first discussion of his scheduled workshop submission, from his manuscript, we witness every writer’s worst nightmare when his professor responds, “Of course, that may be the author’s desire, to portray a writer struggling under the weight of his own clichés” shaming him amongst his peers. Another student joins in, “The main character’s not really someone I want to root for,” said another. And the most lacerating dig: “He comes off like an upper-middle-class whiner.”

Wayne zooms in on the only student who speaks up to defend his narrator–Billy, a struggling outsider from Illinois, who’s crashing in a bar basement to afford to study in his elite ivy-league MFA program. Billy’s talent soon becomes evident to all. Not long after, a transactional relationship unfolds between the narrator who’s desperate for friendship, and Billy who’s in dire need of affordable housing. As the narrator says, “I’d spent more time alone in my living quarters than anyone my age that I knew of, and my social muscles had atrophied.” Wayne’s narrator proposes a deal: Billy gets to live rent-free in exchange for helping keep the apartment clean and cooking occasionally.

The men also edit each other’s work; it soon becomes evident that the narrator is the beneficiary of Billy’s talent. “Most of the time, I feel like a fraud. Like I’m sitting at this big, fancy desk avoiding real work,” says the narrator. “Everyone thinks they’re a fraud,” says Billy. “Except for the actual frauds.”

One of Wayne’s many strengths is his masterful talent for descriptive characterization. He describes Billy, whose jeans “came up an inch or two shy of where they should have dropped—which only called attention to his equally unfashionable sneakers, a dirty pair of white LA Gear high-tops with powder-blue accents.” After that, it’s not hard to visualize Billy. “From the waist up, he fitted in; below, he resembled a Times Square tourist” surrounded by classmates the narrator’s age, “with a few late bloomers in their thirties and forties.” Wayne leans into stereotypes, telling us that “the younger ones struck austere poses with their cigarettes, signifying fierce intellect and tormented inner lives.”

Wayne dials up the tension between his characters. Billy is everything the narrator is not. He’s a hardworking, disciplined, church-going Republican, who’s charismatic in social constructs, especially with women. More importantly, he’s talented. Tension builds as a power struggle ensues, and sexuality separates, rather than connects the two men. The narrator’s discomfort becomes palpably painful, as does his isolation as he reverses roles to become the outsider.

Apartment –which opens slowly, but quickly goes for the jugular–is a portrayal of self-discovery at the expense of self-implosion, as it explores the making and decimating of a close relationship in even closer quarters. It’s what they don’t say that most often divides them. Wayne doesn’t ever reveal that the narrator is queer, but his narrator’s obsession with Billy makes you consider the possibility, especially in relation to his roommate’s homophobic ’90s stance. This is a book whose subtext turns a persona inside out to reveal what lies below the surface and what it means to be comfortable in our skin and in our written voices. While written about writers, the identities challenged are universal.

Billy asks, “What kind of people do you think become artists?” to which the narrator responds, “I suppose it’s people who have something to say, with the talent and discipline to express it, and the empathy to see other viewpoints.” Wayne mirrors preconceived assumptions and exposes the truth. “Sure, that’s all true,” responds Billy. “And also the people who have enough of a financial cushion to fall back on in case they don’t make it. Which means not many people like me.”

Seen through the lens of a writer in an MFA program, while shuttered in during a pandemic, as we’re facing elections in a very Trump versus non-Trump world, this book hits many chords. It helped me face some of my own moral conflicts–like, are great writers made in writing programs mostly affordable to only the privileged? Perhaps, the greater question is: am I a part of an inclusive institution that connects and champions all its writers or one that alienates and discludes those without the dollars to match their talents? This truth, I believe, is the question we all need to ask ourselves, individually and collectively. And what better timing than right now, while we’re scattered around the world at a time where our privileged learning environment can’t shelter us from a virus that even the privileged can’t escape.

Teddy Wayne is the author of the novels Apartment, Loner, The Love Song of Jonny Valentine, and Kapitoil. He is the winner of a Whiting Writers’ Award and an NEA Creative Writing Fellowship as well as a finalist for the Young Lions Fiction Award, PEN/Bingham Prize, and Dayton Literary Peace Prize. A regular contributor to the New York Times, The New Yorker, and McSweeney’s, he has taught at Columbia University and Washington University in St. Louis. He is currently adapting Loner and The Love Song of Jonny Valentine into a series for HBO and MGM Television. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, the writer Kate Greathead, and their children.

LaVonne Elaine Roberts is a short story writer, essayist, and memoirist. She is the interview editor of a literary journal Cagibi, the 2020 Diversity Fellow for Drizzle Review, and a member of the Blue Mountain Review Southern Collective. Her work at Drizzle will include curation of a special issue on ageism, due out summer 2020. Her essays, short stories, and poetry have been published widely, including in Our Stories, Too: Personal Narratives by Women, WordFest Anthology 2019, The Blue Mountain Review, LIT Magazine, Thought Notebook, The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature, Litro, among other publications. She is the founder of WRITE ON!, which facilitates free writing workshops for marginalized populations. She resides in New York City, where she is completing an MFA at The New School and a memoir called Life On My Own Terms.

Teddy Wayne will be interviewed LIVE on Tuesday, March 31st, at 6PM