Self-Guided Study

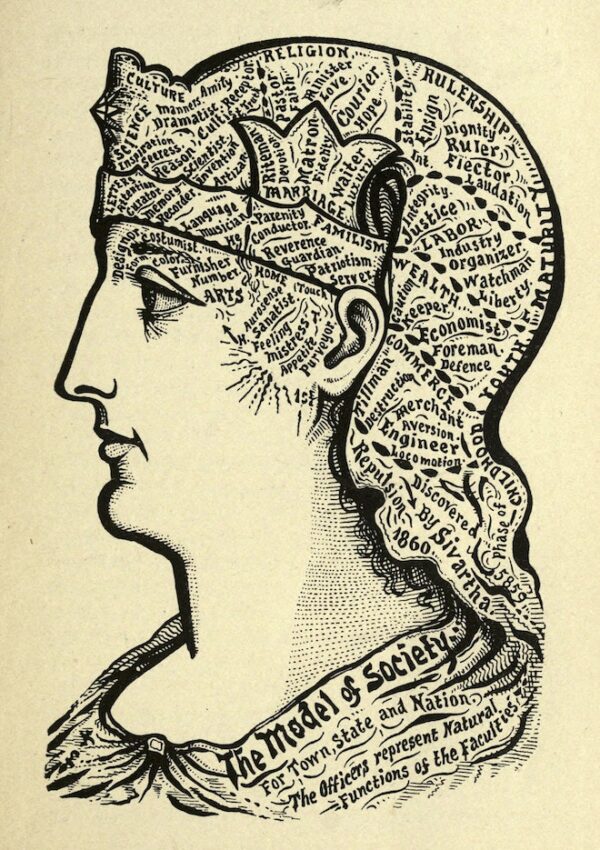

image curtesy of The Public Domain Review

by Meredith Gordon

This quiz is for self-enrichment only. Its content may be triggering.

Any reaction should prompt further self-study. There is one correct

answer for each question, but there are no wrong answers.

A classroom, a back row, a dilemma: A 500-page statistics book sits with

its spine uncracked on your desk. Under your desk, thick, glossy issues of

Cosmopolitan, Glamour, and Self, are splayed open

in your lap. You look down like you’re thinking and hope the teacher won’t

call your name. Articles like “How to Look Like a Happy Couple, Even When

You’re Not” and “Finding Your Path to Professional Happiness and the Man of

Your Dreams” mean more to you than “standard deviation,” “outliers,” and

“protection of human subjects.”

This illustrates:

a. ambivalence about your career choice

b. tension between your inner reality and outer expectations

c. a writing prompt

d. a transcription of a dream

The ambulance brings in the kid strapped to the gurney. The tech with

bowling ball biceps glares at him. The boy won’t stop screaming. The head

nurse, with a white three-fold cap and marshmallow shoes, thrusts a syringe

through the boy’s jeans and into his thigh. The boy passes out and the tech

shakes his head. “Damn. Little motherfucker was giving me a headache.”

This is:

a. the psych unit at the start of the shift

b. the psych unit at the end of the shift

c. the psych unit on Christmas Eve

d. the psych unit during a full moon

There is a chocolate bar on your desk and you want to eat it, but your 2 PM

is here. It’s a couple’s session, but the wife arrives alone with a small

tape recorder, the kind used for dictation that has a little silver speaker.

She places it next to her on the sofa and presses play. Her husband’s voice

crackles through, all tinny, tiny, and far away. It’s his “take on things.”

His “take on things” is that counseling is a crock because you tilt your

head and ask, “How does that make you feel?” And by the way, feelings are a

crock, too. The wife says that your comment about letting her speak without

interruptions got his “goat” and that he ranted about that all week. She

mentions a column in a women’s magazine called “Can This Marriage Be Saved?”

She tells you she wrote to the columnist and is awaiting an answer about her

situation. She feels good about that, she says, and hopes they publish her

letter. You do not tell her that some marriages cannot be saved. She does

not want to attend counseling alone. She peers around the room and points to

the chocolate bar on your desk. That brand is her favorite, so you offer it

to her. She says she will give it to her husband.

Is this:

a. ridiculous

b. proof that food is love

c. smoke and mirrors

d. a true story

The doctor picks up the file and reads it. He tries to remember what he told

the social worker about how they were going to set up charts in the new

year. They hired the social worker because she was supposed to uncomplicate

the doctor’s life by helping with all the documentation he had fallen behind

on with the transition to the new computer system. But now, she has

complicated the doctor’s life because she is too good at documenting and is

better at computering than he is. The doctor wants to fire the social

worker. But he also doesn’t want to fire the social worker because the

doctor wants to flirt with her. The doctor wants to sleep with the social

worker. The doctor wants to be liked and admired, but the social worker is

all business, and the doctor is not used to being ignored. Maybe he will

fire the social worker, even though he had wanted to hire her. But there are

no stupid decisions—right? Or is it that there are no stupid questions?

This is about:

a. a husband and wife

b. a doctor and a social worker

c. the protégé and her mentor

d. the cafeteria lady and her parrot

The trailer smells like human excrement. Excrement has been spread on the

walls and in a stripe down the floor. The patient, age 89, is found in the

unlocked Airstream trailer that was hitched to a Ford pickup truck with no

tires. The trailer is in a lot that had, at one time, housed hundreds of

trailers, including many silver Airstreams like this one, but it has since

been taken over. A sports complex is being built. The patient had already

expired when the social worker arrives. Expired is the word that a social

worker uses on the chart. She does not use die. She does not use

passed away. In this line of work, people have expiration dates.

“Like a carton of milk,” her supervisor says. Inside the trailer, mold grows

on the glasses.

The patient fell in the tiny kitchen that was no bigger than an airplane

lavatory. He was slumped over the toilet next to the sink. The social worker

flings open all the windows and calls her supervisor. She races outside to

breathe, while dragging the thirty-foot phone line down the steps. During

this call, the social worker keeps being asked to return to the inside of

the Airstream, to the decomposing body to obtain the following: patient’s

social security number, next of kin’s telephone number, med sheet, living

will, and insurance card. Requests are given piecemeal. The social worker

does as she is told, vowing to herself that she will quit.

In typical cases like this, the social worker must pretend there is no smell

to avoid perceived slights against the patient. This is to ensure that no

complaints are made to the doctor against the agency because the doctor

might pull referrals, causing a drop in census and revenue.

This is:

a. an example of eminent domain

b. an existential crisis

c. the state of healthcare today

d. the decaying of something old inside, which is turned outward and

released

The psychiatrist walks the patient to the therapy room door and wishes him

good luck. The patient goes in and sits in the empty chair. The patient

becomes agitated upon seeing that the psychologist who is running group is

in deep conversation with a bearded man who is a hospital chaplain. The

hospital chaplain makes his knee touch the psychologist’s knee. Aroused, the

patient gets up and leaves.

This is:

a. the patient’s transference

b. the patient’s libido driving the bus

c. the chaplain’s way of exerting control

d. a memory

You find the note taped to your office door. It’s a little pink page printed

with the words: While You Were Out. The message written on it states:

Your mother called. Twice. She’s holding.

You stare at the blinking red light on the black phone, hearing, feeling,

dreading the lexicon of your mother’s anxiety. It threads through you

intricately, like petit point or crewel, embedded like a primary language.

There are too many metaphors and they all fit. You lift the receiver and

press the flashing cube. “Hello?” Wait, it’s not your mother, and the call

is for someone else. You slump down in your chair and close your eyes, too

aware of the muted voices coming from next office. From the reception area,

you hear the coffee pot hiss and a door close. In the office next to yours,

you hear the muffled sounds of therapy. You swivel your chair between your

desk and the two empty guest chairs. You need to have a little talk with

whomever posted that pink note to your door.

This is a brief study in:

a. attachment theory

b. jumping to conclusions

c. research known colloquially as Pavlov’s dogs

d. the real meaning of psychology today

Down a long hall, the hospital has a room behind a door with many locks. In

the middle of this room, there is a bed, and beneath the bed, there is a

pole that bolts the bed to the floor. There are straps attached to the bed

and buckles attached to the straps, and those straps are long enough to

criss-cross the vinyl mattress. Go off, break down, and crack up, and you

get the mattress, straps, and buckles. By the way, this is how the patients

talk, not you. Seclusion is for fighting, for going AWOL, and then being

fetched three blocks away at Burger King. For being a danger or being in

danger. For veering too close to the edge. For not knowing where you start

or someone else ends. This is how the staff talks. Some patients hate

restraints; the leather bands make them feel trapped. Others beg for them;

they want to be held, and restraints are the only way they feel safe.

Is this a lesson about:

a. what we talk about when we talk about mental health

b. what the boy is question 2 is screaming about

c. pain we all suffer in different ways

d. love

There is a carousel of charts, a black pen, and a cubby. You are taught to

chart with as few words as possible.

What happened? What really happened?

You translate and reduce the complexities of an individual into ordinary

language. There are legal reasons for this, practicalities for taking the

arc of a life and reducing it to pronouns. It saddens you. It scares you how

easily this is done, how normal it seems, how quickly you learn. But it is

harder than writing a story, which is a contrivance of a real life. This

dichotomy makes no sense.

This is an example of:

a. metafiction

b. macroeconomics

c. hospital policy

d. self-awareness

You dream at night about the mind being like a broken piece of bone china

that needs to be held perfectly still so as not to show the lines, the marks

where the pieces broke apart from one another, so as not to fall into jagged

fragments where the edges form points and spires and bulges that might cause

pain if they aren’t put back together the right way.

This is:

a. symbolism

b. real life

c. overly descriptive and distracting, yet you can’t stop thinking about it and it worries you

d. being dramatic

You sit in the corner of your bedroom floor, with a desk lamp teetering on

the carpet and a miniature spotlight on the part where you write in your

college major on the declaration form. You let your finger take you down the

long rows of choices and hover over English. You abandon it and then return

to it. You take the application and pencil in: English. Your

parents scream at you when you tell them. They tell you that you will never

do anything with that major and that they will have nothing to do with you.

So, you go back to your room and sit there and stare at your declaration,

your declaration, with the fear of a child who’s up too late to

read and is afraid of getting caught. The air feels electric and it’s

buzzing in your ears. But you bask in your own words until, finally, you

take the pink Pearl eraser from your desk drawer. You rub the letters one by

one and make your choice and yourself disappear. You put the eraser down

and, as silently as you can, lift the ball point pen and click the

cartridge. You stare at the word MAJOR and the blank space waiting to be

filled. You jam the tip of the pen into the paper, drag it in huge slashes

across the page, shredding the very fiber of your being into pulp.

This is:

a. what you’ve been wanting to say all along

b. an example of unflinching sadness

c. regret

d. the truth

You work with the dying, with people just like your mother. You sit in their

homes, at their bedside, in their living rooms, at their kitchen tables. You

are sent to the homes of people who have fallen, who have been abused, who

have already expired, who are ready to cross over and leave this world

behind. You do clinical assessments. You talk to families. You witness

grief. Between visits, you sit in your car and write in your journal. You

are left-handed, but you force yourself to use your right hand, and it is

more like drawing than writing, more like fingerpainting than composing. You

are bad at it; you are good at it. The past may live inside you, but you are

ready to shed its conventions and resurrect it on a page like this one. You

understand that what comes next has been unfolding inside you, two

narratives at once, a mobius strip and a ticker tape, a mystery from the

depths you’ve longed for, that has been waiting for you all along.

This is:

a. fabulism

b. speculative fiction.

c. a personal statement

d. self-actualization

Meredith Gordon has published creative work in JAMA, Santa Monica Review, Lilith, The Manifest-Station, Literary Mama, Motherwell, Psychology Today, The Washington Post, Citric Acid, Newsweek, Los Angeles Times, and elsewhere. Her story “Patrice” was longlisted for SmokeLong Quarterly’s fiction prize and was published in Flash Fiction Online. She holds a license in clinical social work and is the coauthor of All the Love: Healing Your Heart and Finding Meaning After Pregnancy Loss. Her byline has also appeared as Meredith Resnick. https://meredithresnick.com/