-

Three Poems by Peter Spagnuolo

Above: “The Repast of the Lion” by Henri Rousseau

Cartographer

The monkeys scold that I lost my way, I’ve gone

mad on the march through you, a hand on the whip—

your impenetrable wild I leave undone,

and tame your jungle waste—but wrecked my ship,

so I must spread you open, with no way back.

My rivals tell I’ve grown too old to play

the boy explorer, yet at that perfumed crack

where wells a secret font of youth, I lay

with my discovery, -

Five poems from “Nomad” by João Luís Barreto Guimarães (translated from the Portuguese by António Ladeira and Calvin Olsen) Artwork by Anthony Ulinski

In the photographs of others

I am present in the past of lives I

have no knowledge of (men who saunter to the north

women who are headed south) in

photos

that tied me to several foreign cities

where my face remained retained

by mere chance. A photo is memory

(like a map

is voyage)

in them I’m anonymous at the corner of

a scene

just because I crossed that square

at that time. -

I never sent you that letter that I told you to look out for, by David Greenspan

Our heads were full of yogurt

during those years

of rain and warm rot–

We didn’t pay much attention

to the mudbleat

hiding in our chests–

We drank grapefruit juice

and watched squirrels

chase each other–

You didn’t look at me

stuffed as I was

with glass–

When milk spoiled

and winter was bright,

we talked about

the body’s coarse leak–

O the beautiful shapes

our mouths made to speak–

Anne,

-

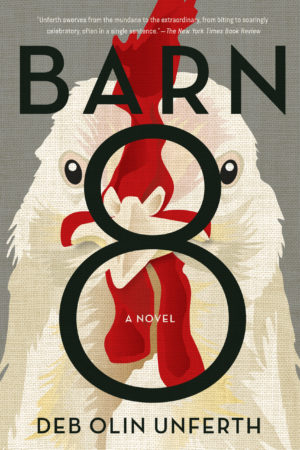

“Barn 8 by Deb Olin Unferth” Reviewed by LaVonne Roberts

I first encountered Deb Olin Unferth at The Arch, Austin’s homeless shelter, when she visited a writer’s workshop, where I volunteered. She has such a generous spirit that feels other-worldly coming from her petite frame. She has something about her—a sense of wonder that has everyone around her wanting to impress her. Not since Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web, has literature humanized an animal to the extent Unferth has in Barn 8. She gives voice to her feathered friends in an endearing way. So, it’s heartbreaking when we learn that hens are slaughtered between a year and a half after being force-molted or artificially light-triggered into laying eggs. Unferth takes her readers on a journey from Brooklyn to Iowa with Janey, a young girl in search of her biological father. Janey arrives only to suffer a significant loss, and the reader is warned that her journey to redemption won’t come easy. _ “It seemed a bit harsh that for the rest of her life, she’d have to pay for one childish mistake she made at age 15, the sort of mistake anyone could have made.” _ Janey and Cleveland, two auditors for the US egg industry, decide to plan a heist of one million chickens. Their madcap caper requires that a wacky, quarrelsome group of activists must work together to free one million chickens in captivity. You realize it’s not so implausible when you hear that Unferth went undercover to write her preemptive essay “Cage Wars” in 2014 for Harpers. Barn 8 is a book you can already envision as a movie because it’s ripe with tension, drama, and movement. Unferth mines the best out of seemingly unloveable characters, just as she reveals the evil lurking behind facade. Unferth’s novel is as philosophically curious as whimsically outrageous. There are times that Barn 8 feels rushed, when one character’s description bleeds into another, feeling like a relay race, but one could argue that Unferth is doing what she does best—bringing all the manic, schizophrenic details of life to the page in real-time. Authors like J. M. Coetzee and Jonathan Franzen have used fiction to illuminate the perils of other species, but few have written from an animal’s perspective. Even fewer have woven an animal’s point of view into a fictional narrative. _ Barn 8 straightforwardly spells out the stakes while at the same time lures you into believing in the impossible. _ Deb Olin Unferth has a literary style like no other. At times her prose feels very Kafkaesque. Sometimes, it feels so dark; and at other times, her whimsicality makes me wonder if studying with George Saunders influenced her humor. Certainly, he must have encouraged her ability to breathe life into her protagonists she lovingly sets free on the page. So much so, that you’re sure Barn 8‘s characters remind you of people you know. What’s spectacular about Unferth’s cast of character’s quotidian lives is not just that you’re rooting for them, but that your world seems a little less mundane as she reminds us what real human connection looks like. It would be easy to chalk up Unferth’s ability to educate the reader in a way that makes them feel smart, but it’s so much more. She understands humanity in a way that no one else does. However, ajar, anxious, or discombobulated Unferth’s characters are, there’s a sense of order to their madness that’s digestible because Unferth’s compassion is infectious. Here’s the funny thing, I haven’t been able to buy eggs or order chicken since reading Barn 8. I’m not quite sure I’m ready to be a vegan, but then, thanks to Unferth, I’m keeping my options open. When you wrote Barn 8, did you write it as a means to catapult activism? One could argue that you’re most content catalyzing a revolution. I didn’t write the book to catapult activism, no. I’m interested in activists, activism, social justice, environmental justice, animal personhood. I want to write about those things and get people thinking about them. I wasn’t writing a polemic. I loved getting an education in the egg industry landscape—like learning that California activists fought and won the right for chickens to be able to “lie down, stand up, fully extend their limbs and turn around freely” in 2008. Your reportage of the approximately 295 million layer hens and the political and legal battles around the country reads like a KGB novel of espionage, spook-level secrecy, and grave consequences. Could you give us some background into the lengths you went to when you did your undercover research for your Harper‘s essay “Cage Wars” and how that led to Barn 8? I realized that to write the book, I needed research. I needed access to the farms. I needed to get to know industry farmers, spend time with chickens, understand undercover investigators. Harper‘s let me write an article on the egg industry, which gave me an excuse to do all of that. Most of what I did was straight journalism: I spent many hours talking to investigators, farmers, scientists, lawyers, watching undercover footage from inside the industry barns, researching chickens, and getting to know them. I went to all kinds of farms, from giant factory farms to tiny ones to sanctuaries. I was obsessed for a while, and I could see how addictive investigative journalism can be. Studies show that when we read nonfiction, we read with our shields up. We are critical and skeptical. But when we are absorbed in a story, we drop our intellectual guard. Do you think fiction is well suited to explore complex philosophical questions? Was it your goal as a storyteller to use fiction to build your readers’ morality? I was a philosophy major, and I’m married to a philosophy professor. Yes, I do think fiction is a good place to think about philosophical questions: _ What is meaningful? What is beauty? What is freedom? Who is a person? _ You shift perspective between your characters by diving into multiple points of view. Why did you decide to move between perspectives? The book circles around one event, one night, what led to it, and the fallout afterward. I liked creating a Cubist perspective, where you could see all angles on what was happening, why people were doing it, what the animals were thinking, what the wind was doing, the insects. History was part of it, too, and the future came into play. It is about a whole community, even the air, which is slowly contaminating. Barn 8 opens to a story about Janey, a 15-year-old girl who finds out her mother has kept the identity of her biological father from her. Your character is split in two after learning of her father – the new Janey and old Janey. There’s a restlessness in Janey’s nature that feels so real. How did you develop Janey’s character so authentically? Is questioning one’s birth origin a subject close to you? Restless characters are human characters. We are questers. I wanted Janey to have a connection to the Midwest but to feel lost there. I met you in a homeless shelter while I was volunteering, and you were a guest author/teacher. As you thoughtfully responded to every participant, I thought about your ongoing work in prisons. I wondered about the cornucopia of writers work you read, from MFA students to incarcerated writers. How do their stories influence your writing? I’ve been teaching for so long—since my second year of grad school—I’ve barely been a writer without teaching being part of it. And yeah, I love teaching and all kinds of places. I like getting to know all sorts of people who are different from me or similar, all of us coming together and talking about stories. It’s hard to say how they influence me because I have so rarely been without them all these years. I like people. Because of your Harper’s essay, we know about the anonymous donor who paid to charter a cargo plane to fly nearly 1,200 chickens across the country to New York. I picture you driving to visit 100 of those chickens at the sanctuary you wrote about in Manchester, Michigan. Now, I think about all the times I reached for commercially produced eggs at a third of the cost of free-range eggs before Barn 8 with remorse. How do we lower the price of eggs so that single moms on welfare can afford to buy them responsibly? We can’t. There are better things to eat anyway. Beans are just as cheap and are better for you. Peanut butter gives you a better punch of protein and isn’t loaded with cholesterol or inoculation byproduct. _ We don’t need eggs. We don’t need them for baking, we don’t need them as cheap protein, and we don’t need them for Easter. _ For writers, it becomes imperative to find joy and humor in life off the page. What are the ways that you offset your writing and teaching? I like hanging out with my husband and dog. I like hanging out with my old parents, my tiny nieces, and my sister. I have a little gang of friends that I like to meet up with, and I like nature. You leave crumbs worthy of a literary forensicist, like your inclusion of Austrian architect, Victor Gruen, or the fact you named Olive after your editor’s daughter. Is it deliberate or subconscious? I’m so glad that you noticed Olive! She entered in a later draft of the book when my editor and I were already working together. I put her in almost without thinking, and then I realized what I’d done, and I was delighted. _ I just pull in the world around me—it’s not conscious or unconscious. It’s just writing. _ You’ve mentioned that there is a bit of you in every character. Which character is or was most you? At the end of the book there is a park ranger who is watching a tremendous amount of TV. Now, I seriously never have been a huge TV watcher, though I do watch some. But there was a time several years ago, when I was first starting this book, that, I don’t know, I got into a funk and couldn’t do anything. I mean, there was something really wrong with me. My husband and I had jobs in different states that year and only saw each other one or two weekends a month. I started watching TV and could not stop. I’d try not to start watching it until at least after dinner, but I couldn’t help turning it on as soon as I got home from school. I’d try turning it off by ten, but I watched later and later until I was going to sleep at four in the morning and getting up at ten, hurrying to school bleary-eyed, and coming home and turning it on the second I got in the door. This went on for months and months. It was a disaster. But in those months I wrote the passages that turned out to be that character. The character is watching so much TV but still manages to complete an important act (I won’t say what) that makes the end of the book possible. And there I was, watching so much TV but still managing to write the passages that would lead me to the book. * Deb Olin Unferth is the author of six books, including Barn 8 and Wait Till You See Me Dance. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and three Pushcart Prizes and was a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist. Her work has appeared in Granta, Harper’s, McSweeney’s, and the Paris Review. * Tune in Tuesday, April 28th at 6pm when Deb Olin Unferth will join us for an interview on LIVE with LIT

-

Two Poems by Martin Rock

Lines Written After a Party in New York

It isn’t sarcasm or sadness but the feeling

of having been left to die in the middle

of a rooftop filled with one’s attractive friends.

They look at me and I try to look at them.

My eyes remain fixed on the side of my head.

My tongue is a fist submerged in ice.

I try to make my way back to the surface

to bleat but I cannot. My eyes are glassy

& probing & panicky & -

Global Voices Interviews *Poland* Bronka Nowicka and Katarzyna Szuster in conversation with LIT’s JP Apruzzese

The Polish version of this interview appeared in Biuro Literackie on 23 March 2020

Every so often a writer comes along who shows us what literature can and perhaps is meant to do — offering not so much a different perspective as a different way of seeing. A writer whose work inhabits a space undetermined by convention, trends, topics of current interest, unafraid to put aside the noise of daily life and explore the unnoticed – unseen because ignored – life that is nevertheless fully within our grasp.