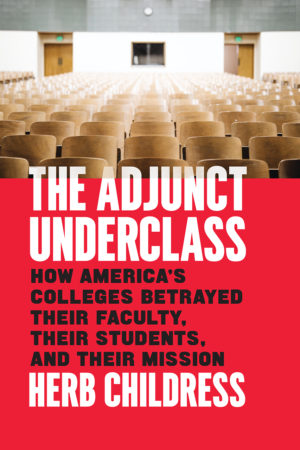

“The Adjunct Underclass by Herb Childress” Reviewed by Scott Wordsman

What was the adjunct? A dialectical approach to faculty contingency on America’s campuses

There are two distinct points of friction within American higher education, which, if thought about long enough, seem to feed off each other, and have, for decades, been rendering America’s campuses graveyards of critical thought. The first is the transformation of what was traditionally deemed a public good into a commodified entrance pass into the professional world. This, among other absurdities, begets the ubiquitous but what are you going to do with that? question from relatives who couldn’t fathom why anyone would pursue, on its merit alone, a humanities degree. Yet the hapless uncle, in this case, is blameless, for this is how we have been conditioned to approach education.

As American journalist Chris Hedges has stated, the university as a pillar of liberal society has succumbed, as have the rest of our failing democratic institutions, to the dictates of the corporate state. Honest intellectual inquiry has been replaced by rote metrics-testing, training in narrow disciplines, and feckless deference to authority, all of which have produced hyper-individualistic, instrumental attitudes toward education. Good artist? Study advertising. Talented writer? Pick up that concentration in Corporate Storytelling.

The second point of friction, which is a bit more revealing of an unsustainable economic model, is the preponderance of university faculty who are paid as contractual, temporary workers–most notably at working- and middle-class colleges and universities. These teachers often slink by the public eye undetected: either by choice (they’re too proud to relay their plight) or inconvenience (they’re too busy working sixty-hour weeks with no promise of employment next semester). These temporary workers are the adjunct faculty, the foot soldiers of the neoliberal university and the inspiration for Herb Childress’ wide-eyed account of how they came to be: The Adjunct Underclass: How America’s Colleges Betrayed Their Faculty, Their Students, and Their Mission.

For those unfamiliar with the work, life, and schedule of an adjunct, you are not alone. Even the adjunct has no idea what she’s doing, how she’s doing it, or why she persists. Perhaps it’s the commitment to the craft and the students, or maybe it’s the vague promise of full, secure employment that years of positive reviews and overloaded semesters should, in a just system, engender. Childress, however, decries this as bunk, claiming that only a small percent of professors have the pedigree desired to become full-time:

Becoming a [tenure-track] faculty member now is no different from becoming a professional hockey player…Your competitors will have had every advantage life can offer, and you have to match them somehow…that means moving directly from a home with books and ideas through a strong undergraduate program and into a strong doctoral program, with no significant time away for work or musing on one’s life. It means moving swiftly through that doctoral program, preferably working in research assistantships that foster both coauthorship and recognition by major funding agencies…Arriving at the doctorate by one’s late twenties or early thirties, the new scholar is then recognizable by similarly trained and similarly privileged colleagues (61).

Ultimately a deeper excavation of social stratification is necessary for revealing the insidious nature of American professional life. For even in a field as ostensibly performance-based as academia, class matters. Intellect and curiosity are secondary; having gone to the right school and having worked under and alongside the right people carry much more sway. Is this, for lack of a better word, fair? Not at all. It never was, but that’s not the point. What matters is that as long as the illusion of meritocracy–that you can come from nothing and become something–is kept alive by the propagation of a near-dead American dream, hundreds of thousands of adjuncts will continue to work longer hours for less pay, their hopes of tenured employment seemingly in reach and concurrently in flames. (The average adjunct, keep in mind, makes $2500 per 3-credit course, while the incoming assistant professor makes roughly $70,000.)

This idea of “hope” is an exploitable necessity within the university enterprise in no less the same way that the dream of landing That Big Promotion coaxes salaried corporate workers into staying on the clock later and later each day and week. This contingency model, which preys on fears of downsizing and potential future automation, is an employer’s dream. This fear, coupled with the erosion of unions and pensions, forces workers in every sector to accept longer hours for less pay–what historian Michael Parenti has called the third-worldization of the American economy. These extra hours, this hope labor, defined by researchers Kathleen Kuehn and Thomas Corrigan, entails the “un- or under-compensated work carried out in the present, often for experience or exposure, with the hope that future employment opportunities may follow.” For the adjunct, this unseen work includes drafting syllabi and course calendars, answering emails, writing letters of recommendation, archiving documents, creating tests, and mentoring students. Hope labor also encompasses voluntary service and scholarship: writing and publishing, presenting at conferences, serving on advisory boards, attending departmental meetings, and sundry other duties. Some of these are passion projects, but most are done to keep resumes beefed-up and current, should a tenure-track line open up, which, as Childress notes, is becoming more and more unlikely, as the majority of federal and donor money is spent on new buildings, grounds, athletic teams, student support staff, and–as every complex bureaucracy demands–more and more administrators. What these administrators do varies, as do their titles, but for the most part, their jobs are to increase revenue streams through two outlets: fundraising and managing labor. More money in, less money spent. This is hardly a Marxist analysis.

Before we break down where the money is allocated, and why, an important distinction to make is that not every university is created or funded equally. Invoking Jean Anyon’s The Hidden Curriculum, Childress lays out the tiers of higher ed in the US, which, essentially, replicate the caste system into which its students flow and often remain. The working-class attends vocational schools or community colleges; the middle-class attends public state and regional universities, the children of the professional class frequent the liberal arts colleges and large, often private, universities; while the 1 percent send their ilk to the hallowed halls of the Ivy League, Stanford, and Duke, where they sharpen their analytical skills, network with the children of actors and magnates, and maintain fluency in “the easy language of privilege and comfort.”

While it goes without saying that certain schools evoke more oohs and ahhs from hiring committees, the rich maintain and reproduce their class interests in more ways than one, and that is because private colleges and research universities with large alumni endowments are not at the whim of austere state and federal budgets (and thus not strapped for crucial funds). They have the money to spend on a largely permanent teaching base, which bestows upon its students numerous benefits–the ability to maintain ongoing relationships with faculty chief among them. A first-year student attending a community college or four-year state university, on the other hand, will be taught primarily by adjuncts for the first few semesters. Though many adjuncts, Childress notes, are skilled and gifted teachers, they generally don’t have their own offices nor the time between classes to establish relationships with students. Universities also rarely pay adjuncts to attend departmental meetings and retreats, which isolates them from current pedagogical practices and trends. This lack of investment in public school faculty has palpable effects. A first-semester student at a community college has a fifteen percent chance to graduate from a four-year university, while the graduation rates at top private liberal arts colleges buoy around 90 percent (Childress, 2019, p. 42).

Due to long hours spent in the classroom, as well as grading and commuting, adjuncts do not have the career capital that tenured employees have had the time and resources to accumulate. In turn, public school students learn from teachers who are not only overworked, but scholastically underdeveloped. Impossible to ignore is the element of institutional violence on display: if you are a have, you will be taught by the haves; if you are a have-not, you will be taught by the have-lesses and have-nots. The economics follow suit. Tuition for students at in-state, four-year public universities has risen, on average, 371 percent (adjusted for inflation) within the past forty years (Childress, 2019, p. 70). These hikes force economically precarious students to take out loans and work part-time jobs to make up for the deficit, all the while being fed the dogma that if you can’t afford it, maybe it’s because you shouldn’t have it. Never before in history, argues Henry Giroux, has a generation been so cast off as disposable, decried as lazy and frivolous, and responsible for their own lot in life as today’s youth, who are constantly being fleeced by the state for the funding and maintenance of a brutal neoliberal order. In Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education, Giroux documents the 2012 Quebec student strikes, a response to the regressive Charest government’s plan to increase tuition at Quebec universities by roughly 75% over a five-year period. To quell the strikes, the government unveiled Bill 78, “legislation viewed as an attempt to break student unions, suppress democratic expression, bankrupt individuals, and undermine the unity and solidarity forged among the largest student groups” (Giroux, 2014, p. 168). Bill 78 eventually turned into the draconian Law 12, which gave law enforcement the ability to administer $125,000 fines for unions and $35,000 for individuals who sought to break the law by means of dissent. The business community backed the legislation, showing 95 percent support for tuition increases, while the bourgeois media–Globe and Mail, for example–decried the students as “self-seeking brats, whining about modest tuition increases and seeking mayhem for its own sake”. This “modest hike” would’ve raised about $200 million for the Charest regime, which had no problem contributing $4.5 billion to Canada’s bloated military budget (Giroux, 2014, p. 171). This was an unveiled tax on the poor and young.

Drawing inspiration from the Quebecois, student activism in the US has picked up, with student groups and adjunct unions forming to address tuition hikes, budget cuts, labor disputes, and other nefarious, antidemocratic activities. In his book, Giroux, highlights some of this activity, noting that Penn State receives millions in grants and contracts from the Defense Department each year; the Koch Brothers once pledged $1.5 million to Florida State University to ensure that new hires within the economics department , and–in all-too-telling fashion–”BB&T Corporation, a financial holdings company, gave a $1 million gift to Marshall University’s business school on the condition that Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand be taught in a course” (Giroux, 2014, p. 139). Over the last forty years, the neoliberal project, with its allegiance to the corporate state and military industrial complex, has been largely successful in undermining the public university system by commodifying education and depriving students and faculty of the resources they need to become capable, rational agents. In the way that colonialism has drained the labor and wealth of naturally rich nations, so too does the state commit economic and intellectual violence against those who seek out or provide a public good. Therefore, American students, teachers, and public schools are not underdeveloped–they’ve been maldeveloped.

What is to be done about the adjunct crisis? The university crisis in general? Childress doesn’t have a quick salve, but the problem, he argues, requires systemic change. In the way that incremental reforms will never quell the excesses of capitalism, bandages will not heal the ruptured university. A radical revision is needed, namely one that defies market logic and restores power back to the students and faculty such that the focus on human relationships can supplant the current mode of transactional information exchange. “We are not merely economic units,” he writes in closing:

Every person has a particular blend of knowledge and enthusiasms, of capabilities and concerns. Rather than trim some of that away as extraneous, outside our discipline or body of knowledge, colleges would begin with the presumption that we are all entire, that nothing about us is extraneous…A college based on relationships would not allow for the instrumental treatment of any of its members, would not permit exploitation of teacher, student, groundskeeper, or football player…and every person within [the college] would change its chemistry in small but knowable ways (149).

Childress’ proposal of a revised university, one that has emancipated itself fully from the tyranny of the market, harkens back to some of the questions asked by the Frankfurt School. How, in a post-industrial, alienated society, can we become more fully human? Max Horkheimer believed that the way to do this was to oppose the instrumentalization and the “retrogression of individuality” at the hands of the corporate state. As the demands of capitalism penetrate the family, childhood becomes foreshortened. While the young, in the industrial period, went to the factories at their earliest available age–to make money and subsequently adopt the habits of their parents–children in the knowledge economy are gifted a different sort of totalizing labor: compulsory socialization. In Critique of Instrumental Reason (1967), Horkheimer considers the rationalization of the personal sphere:

How many circumstances are conspiring to disaccustom the individual to friendship, despite all the increased cultivation of acquaintances, all the proliferation of consultations, conferences, business trips, and tourist journeys?…Behind the stereotyped smile and diligent optimism the isolation is growing more intense…The more that education is removed from the family…and shifted to institutions…the less stimulus there will be to preserve and develop personal distinctions and nuances. The personal psychic traits which individuals retain become increasingly a hindrance, something peculiar (93).

Is this not relevant today? What is the function of the university but to serve as the last stop on a childhood’s worth of pre-workplace socialization? If this was not the case, there would be no room on campus for business schools or networking events. (The business community, as we know, works in opposition to education, constantly underfunding schools, denying teachers pensions, and, as mentioned earlier, funneling money into programs to manufacture consent for right-wing agendas.)

The goal of education now, as Childress and other scholars argue, is to lay bare the destructive forces which seek to undermine education, so as to foster in students consciousness: about the world, who owns it, and what they do to keep it that way. As Paulo Freire wrote in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, “the more the people unveil this challenging reality which is to be the object of their transforming action, the more critically they enter that reality.”

It is no longer enough to think the classroom can exist without addressing the economic austerity and environmental degradation at the hands of the elites. The political shapes all conversations had within and outside the university, and all ranks of faculty should see it as their mission to make this reality clear. Only when the dialectical relationship between the adjunct faculty and the contradictions of capitalism are addressed, and only when communion between students and faculty is prioritized and not seen as secondary to the goals of liberation, will education be able to decouple itself from the current order. The Adjunct Underclass is a good manual for anyone wondering which steps should be the first to take.

*

Scott Wordsman is an adjunct professor at three colleges within the NYC area. His poems and essays can be found in The Rumpus, Colorado Review, THRUSH, Coldfront, and elsewhere. Scott lives in Jersey City, where he runs the Uncle Fuggles Reading & Music Series.