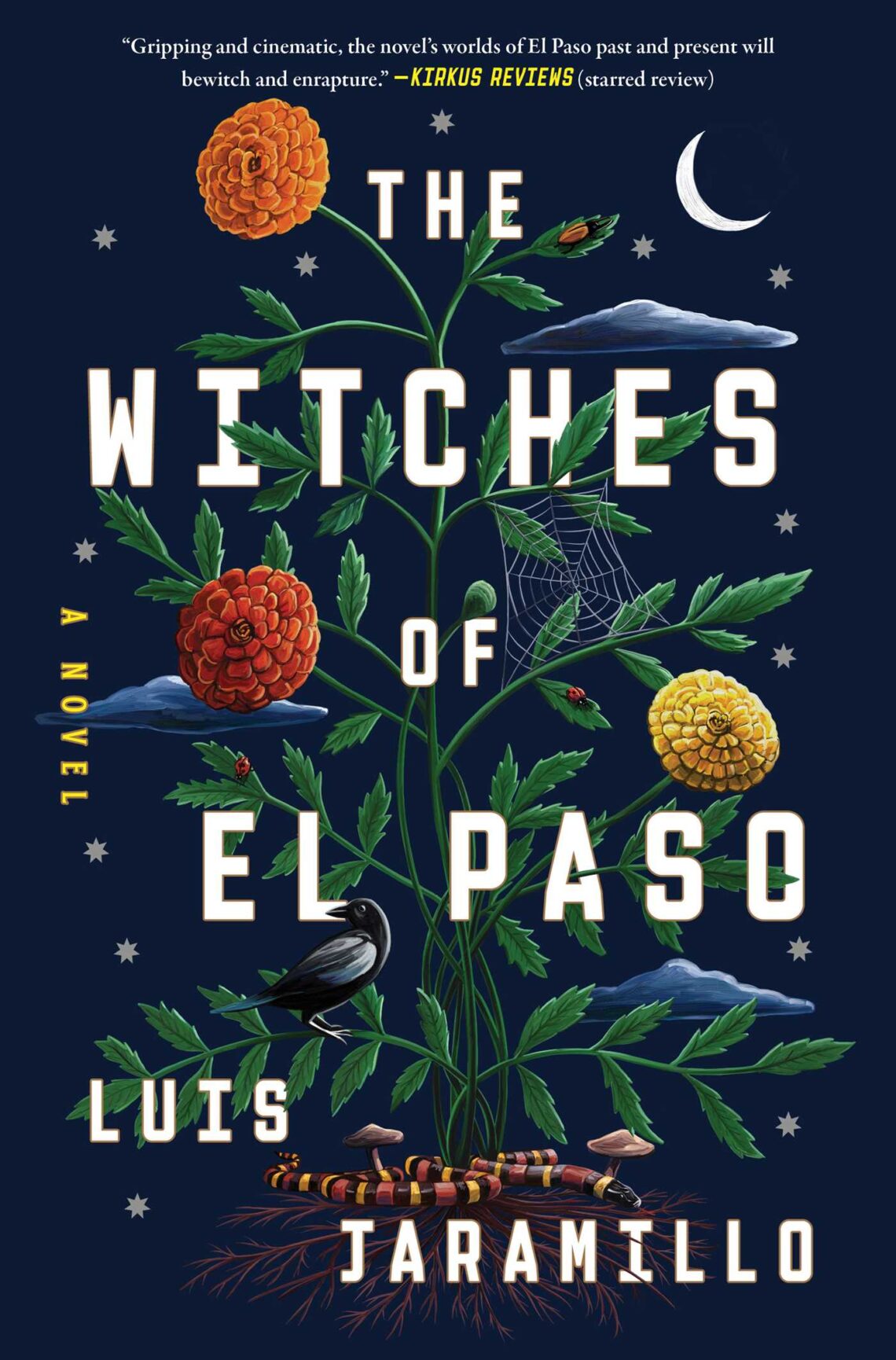

Time Travel and Witches: an interview with TNS Creative Writing Professor Luis Jaramillo about his debut novel, “The Witches of El Paso”

by LIT Books Editor, Jonathan Kesh

Equal parts historical and fantastical, The Witches of El Paso is a spirited exploration of the many ways we try and often fail to control the world around us, and it’s the debut novel from New School professor (and former director of the Creative Writing Program) Luis Jaramillo.

The story begins as a classic family saga, but quickly grows stranger: in the present day, bustling lawyer Marta cares for her elderly great aunt Nena, all while the old woman insists both of them have La Vista, a powerful supernatural force which can be summoned but not often controlled. Nena’s telling the truth — interspersed with this storyline is the tale of a much younger Nena in 1943, who surprises herself with troublesome, seemingly psychic abilities until she accidentally transports herself into the far past. Clueless about how to return, the teenage Nena becomes stuck, and leaves behind a piece of herself which she yearns to recover even in her present-day old age, when she knows the end isn’t far off.

A truly non-chronological narrative, the spiderweb-like structure of The Witches of El Paso stays clear and easy to follow even as we leap through time from chapter to chapter. It helps quite a bit that Nena herself is so grounded, with relatable feelings written out in compassionate prose, even as her life explodes in magical chaos around her. La Vista is inscrutable to its characters, but the characters are perfectly scrutable to us.

Luis Jaramillo’s novel came out in October from Atria/Primero Sueño Press. Shortly before its release, he spoke to LIT about how to assemble so many different stories into a single tale without getting lost in La Vista.

LIT Magazine: What was your original vision for The Witches of El Paso when you first began working on it? Where did that initial spark of inspiration come from?

Luis Jaramillo: Well, I started to work on something that looked very different, so it really wasn’t until I went to Sewanee, the writer’s conference. Tony Earley was the workshop instructor that I worked with. I was a fellow and I didn’t get workshopped, but he read my submission. And, when I was putting the submission together, I sort of threw this little bit in at the end that I was really unsure about. And so when we talked about it, he was like, “Well this is an MS and you know it. Right?”

And I said, “Well I guess so.” But then he was like, “But here this is where the energy is.” And he pointed at the character Nena, who had recently come to me and I hadn’t known what to do with her. She’s the character who is able to talk to the dead and it’s sort of unclear what she’s able to do from the outside. When he said that’s where the story was, I decided to go with that for a while. Then I just sat down later that summer and started to handwrite a draft of the book, starting with Nena’s voice.

So the character Nena who has these magical powers, I suppose you could say, came to me about a year after trying to write something else. Once I heard her voice, I had a much clearer sense of what the story was.

LIT: So in this original submission, Nena was a much smaller character?

LJ: Oh, yes. She was a much smaller character. She was one of the sisters. I mean, it doesn’t really matter what the other story was, I can’t even remember but it was pretty, pretty boring. I think it had something to do with Medicare fraud and there was a doctor and I don’t know. It was something that didn’t have the same kind of energy that I suddenly felt once Nena appeared.

LIT: You mentioned you handwrote the first draft. Do you feel handwriting is easier than typing?

LJ: I’d never written anything that long handwritten. But the thing about handwriting, especially that first draft, is that it really forced me to think about the story and to keep going forward with the story. I couldn’t jump around in time, in the chronology. I just had to think about what happened, or how things caused each other. One scene would cause the next, cause the next, cause the next.

A lot of what I wrote in that first draft, even if the events are different, the feeling of the story is the same. The structure got a lot more complicated, but the handwriting definitely kept me honest. I couldn’t jump around and be distracted. I really had to focus on starting a scene, finishing a scene, and then thinking about what was caused by the scene that I had just finished. What were the questions I raised? What did I then need to do?

LIT: When I was a student in your novel writing workshop, we talked a lot about structure. Witches of El Paso is unique in that in the final draft, it’s split fairly evenly into this past and present section, and the two often parallel and foreshadow each other. You mentioned that you originally wrote it much more chronologically in the first draft, so how did you create that final structure while you were revising it?

LJ: In the first draft, I was focusing on Nena’s story, and there wasn’t another character. And I felt that eventually, I needed to bring in this other character to give more context to the story. Maybe not historical context, but political context. So once I brought the Marta character in, usually what I did in each draft was separate the two stories completely and work on them separately so that they made sense on their own.

And I was usually pretty surprised at what happened when I put the stories back together again and how they talked to each other, once they were next to each other. It was fun to see what happened, because I was always worried that I would have to do more work to bring them together. Thank you for saying that they foreshadowed each other and played off of each other because that was my intention. But I also felt like I didn’t want to force that too much so that it felt inorganic.

But then the other thing I had to do was make sure both stories met up at the end. That did take some work: Nena’s story, which is occurring in the 1940s and in the late 18th century, and then Marta’s story, which is happening now. There are events in both the stories that coincide, because of the time travel stuff.

LIT: There are a few different genres at play here. Mainly magical realism, but a lot of historical fiction as well. What was your research process for bringing 1792 El Paso to life?

LJ: So I did a lot of reading. Some pretty academic, historical books, because it was hard to find stuff about colonial Mexico that wasn’t academic. But all the academic books had at least a few bits of things that I could use, like really great details. There was a book of recipes that was actually in Spanish. I had to dig through that and try my best with the Spanish.

But then there’s a book about nuns. It’s a book about rebellious nuns who were in revolt against the bishop they were under. That was interesting. And then there’s another book that was just about convents in colonial Mexico, basically every little bit of the way that the convents were structured, the day-to-day. And then what was really useful, there were quotes from letters that they had written to either family members or to other clergy. And so those really specific details are the ones I used in the book.

Other kinds of research, my family is from El Paso. And so I visited a number of times over the years and talked to many different people. You know, people who worked with immigrants, lawyers, people who taught history at UTEP (University of Texas at El Paso). I talked to a historian who writes a more narrative kind of history about El Paso when I was there.

And then lots of family members. Some of them have very good memories and then other ones don’t. So I gravitated toward the family members who have specific memories and the ones who were able to connect things for me, with history and the present time. On my most recent trip I took, my dad’s cousin David drove me around. That was really helpful, just looking at things that I remembered from when I was a kid, but he’s somebody who’s lived in El Paso his whole life, taught high school, coached soccer, and so he just knows a ton of people. And he’s one of those people who really has the gift of gab, too. So he, you know, has all sorts of stories and was very generous in sharing them with me.

LIT: Was the witchcraft and the magic behind La Vista — the central supernatural force in the story — influenced by folklore or anything you found during your research, or was it a wholly original creation for the novel?

LJ: I can’t say that I completely made it up. I think it has to be a mix of what magic looks like in many other books that I’ve read. But at a certain point, I have a very clear memory of my agent saying to me, “What are the rules of La Vista?” So I had to really think about it in terms of how it functioned in the story, but then also how I wanted it to function as a metaphor.

For me, the most important thing about it was that it was this uncontrollable force that is very like nature — I think I say that in the book — but is also a creative force. Creation in terms of sex and childbirth, but then also creation in terms of writing and art making. And how that power is something that animates my own life, that awareness of the power of nature and the power of creativity, and how these are very mysterious things, nature and creativity. It’s not something that can be bottled.

LIT: The character Marta tries to use La Vista for larger, political means, a lot of characters use it more personally. Some people see it as evil, but it’s also very religious for other characters. Did you see La Vista as a positive or negative force, or something different?

LJ: I think I saw it as a force. I really was thinking about it like nature, so nature is just creation and destruction constantly. Maybe there’s a morality to it, but it’s hard to see it most of the time with nature, the way that things are made and destroyed. There’s a cycle that is never ending. Depending on where you look at the cycle, it seems like things may be bad or good — destruction seems bad, but on the other hand, destruction is also necessary.

In the book, there are characters who I think are actually pretty bad, pretty evil. And I don’t think I’ve come down on whether they have more La Vista in them or not. I just think that it’s this force that that’s in everybody, and then there’s our own human impulses that interact with it. But they’re distinct from each other even though they’re always related because, you know, we’re alive.

LIT: Between the two main POVs we see in this book — Marta, this high intensity lawyer who exists mostly in the modern day, and the more reserved Nena who spans a few different timelines — was one character easier to write than the other? Did one of their voices come more naturally?

LJ: Yeah. I think Nena’s voice I heard right away, and it was much easier to see her motivations and hear just because I could hear the language. And then she’s doing fun things too, a lot of stuff happens with her. She goes back in time, she has to live with these witches, she’s able to talk to the dead.

But then I also thought that I need to have a more skeptical character. The more skeptical character is Marta, who’s this lawyer, a mother, and she’s somebody who feels she needs to control things, and control her life. Except that she’s facing down middle age and realizing that there are many things that she can’t control. And so she’s at a point of crisis, you know, wanting to change things and not sure how. It took me a while to get to that point with her, to really see that’s what her issue was, and to not just have her be a skeptic. Because then what does she want?

At one point, I wrote a draft or a couple of drafts where she was having an affair, but then that seemed wrong. So Marta, because I think she’s not as fun of a character, was a little harder to write. But on the other hand, I felt like I needed to have that grounding sort of character so that Nena could be as wild as she is.

LIT: A previous book of yours, The Doctor’s Wife, also followed multiple generations of a single family, but that was technically a short story collection. How did writing The Witches of El Paso compare to the “short flashes” of stories in The Doctor’s Wife?

LJ: Short flashes, I’m just going to be honest, are a lot easier to write than a novel with a sustained plot and narrative, or I should say two plots. The short pieces I wrote individually, shuffled them around, and finally put them in order. It’s also a much shorter book. That book was called a book of short stories, but there was one narrative. And many of the stories were stories that I pulled from my family’s life and from research in my family’s life, but I made up enough that I couldn’t call it nonfiction.

But I wasn’t trying to make stuff up when I was trying to write that book. I was really trying to be as accurate as I could, whatever that meant, and thinking about those little flashes like poems. So there’s some stuff that couldn’t be proved, but I was trying to get the emotional truth, and use as many physical and central details as I could to make it seem as grounded as it could in reality.

For The Witches of El Paso, I really wanted to write a book that had a plot and had characters who had things at stake, and to have something really happen at the end. And that’s a whole different process and it’s a lot harder to do.

LIT: Now that The Witches of El Paso is finished, do you have any new projects you’re currently working on or that you’re able to talk about?

LJ: Yes. I’m working on two things. One I put to the side, I have a couple of drafts of a novel set in Salinas, California where I grew up. It’s set during the birth of the bagged lettuce industry, in the late nineties, as there’s upheaval in town and some people were getting really rich. It’s about this farming family and the best friend of the farming family’s daughter, and about what happens to the property and the family when the patriarch dies. In his will, he says his children have to get legally married to inherit the money. And his son is gay.

There ends up being kind of a love story, a complicated love story. I was thinking about how to remake The Marriage Plot in a more modern kind of a way, now that The Marriage Plot in some ways can’t exist because we don’t have the same kind of constraints currently on marriage and divorce and that kind of thing. Anyhow, I put that to the side because I was feeling a little bit stuck, and not as interested.

And now I started a new book that’s a thriller, it begins in the Caribbean. I’m obsessed with sailing, and so there’s quite a bit of sailing in it. And they’re grifters — they start on a trail in national park in the Caribbean. And these people meet each other, and no one is who they seem to be, it’s been fun. I started it about a month ago.

LIT: Do you have any new advice for students or anybody else currently working on a novel? It can just be one or two things, I know that’s a big question.

LJ: I think my advice is the same as it always is, and it’s my advice to myself too, which is to be patient. It’s the hardest kind of thing to hear, because everybody has good days and bad days when they’re writing. And on the bad days, it’s really bad. Or when you’re waiting to hear back from an agent or when you’re doing revisions with an editor, there’s a lot of waiting and hard stuff. But I think the only thing we can do as writers is to keep on writing.

So, one reason I started the thriller is because I have this book coming out now, and there’s nothing I can do about what happens with it now. The only thing I can do is put my energy into creating something new. And I’ve done this long enough that I know that I’m going to have some bad days in the writing, and that’s just how it is.

The Witches of El Paso was published by Atria/Primero Sueño Press on October 8, 2024

Luis Jaramillo is the author of The Witches of El Paso and the award-winning short story collection, The Doctor’s Wife. His writing has appeared in LitHub, BOMB Magazine, Los Angeles Review of Books, and other publications. He is an assistant professor of creative writing at The New School. He received an undergraduate degree from Stanford University and an MFA from The New School. Find out more at LuisJaramillo.com.