Translating Empathy in a Time of War

Global Voices – Letter from Poland

Katarzyna Szuster-Tardi & Mark Tardi

At a slightly different historical moment, they could have been our grandparents – or us. They come from places with names that are familiar, like Kyiv, Lviv, and Odessa as well as from places that weren’t part of our mental map a few weeks ago – like Kryvyi Rih and Kherson. All of them have had to leave behind what they know and love: partners, relatives, friends, landscapes, pets. They’ve brought with them what they could: a few changes of clothes and whatever else one might grab when the pulse drum of panic and self-preservation are confronted with two enemies, fleeting time and the imminent cruelty of the Russian military.

In the span of just three weeks, Poland has taken in a population of Ukrainians roughly equivalent to the entire population of Warsaw (as of this writing, more than two million people with the number only growing). Poles from all over the country and all walks of life have risen to the extraordinary challenge Russia’s unconscionable invasion of Ukraine has presented and Polish generosity has taken every shape imaginable – whether it’s raising funds for numerous NGOs and international organizations to help within Ukraine and with the swell of refugees in Poland; collecting food, clothing, and basic necessities for those coming into Poland; or opening their homes and hearts to provide a safe place for Ukrainians (the overwhelming majority of whom are women and children) coming into the country.

Seeing what was happening in Ukraine, Poles sprung into action immediately. Some drove to entry points at the border to personally transport people to various homes and shelters. Others brought warm meals and teddies for children. At the University of Łódź, where Ukrainians have been a strong part of our student body for many years, the University established a fund to help the students, set up numerous collection points across campus, and opened the dormitories to their families. For our part, throughout our lives and careers, we’ve benefitted from the visible (as well as invisible) support of others, so it seemed obvious to us at such a precarious moment that, like so many other Polish families, we would offer shelter and support to a Ukrainian family needing refuge.

Ours is an international home, the marriage of two people, countries, and languages. We are both lovers of books, literature, and translation, and view literature as an empathetic international dialogue that enables myriad forms of travel: cultural, emotional, historical, intellectual, and temporal. Tragically, under Vladimir Putin’s order, the Russian military invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022. This year, that date fell on Tłusty Czwartek (Fat Thursday), the Thursday preceding the start of Lent and a day that Poles normally celebrate by eating more than a few pączki (Polish donuts) – it’s similar to the way American Catholics take in Mardi Gras. (In cities with large Polish communities, such as Chicago, Poles and non-Poles alike enjoy what they call “Pączki Day.”) Rather than celebrating a day of pastry-based hedonism, however, Poles saw the opening salvo of ongoing horror inflicted upon their neighbors to the east.

As the number of refugees has swelled, some tensions are becoming palpable. Some armchair Polish historians spleen about Ukrainian misdeeds during World War II as if the current Russian invasion of Ukraine is some kind of imagined payback for events eight decades ago. (These amateur historians are analogous to the uncles Americans dread seeing on Thanksgiving.) It’s worth noting that Ukrainian refugees are eligible for social benefits in Poland, can travel free of charge on trains and buses, and receive free health care. Ukrainian children can start education in Polish schools and enjoy some initiatives, such as free movie tickets for certain shows with Ukrainian dubbing – all designed to get the kids’ minds off the topic of war, at least for an afternoon. Not everyone in Poland embraces these actions and gestures; some are disgruntled that they are happening at the expense of Polish society (the classic: “They’re here to take our jobs”) and that such concessions are not extended to an average Pole. These voices, however, are generally fought back: “Your home has been ripped apart, literally and metaphorically, but sure, these free tram rides are a sweet deal.”

Both the refugees, the families offering them shelter, and the volunteers are finding themselves not only in need of material help but also psychological support. Groups are being formed to address these needs, and to guide Poles around the minutia of paperwork to be filled in and offices to be visited while trying to help sort out all the legal matters for their Ukrainian guests. Some psychologists have started to speak of the darker sides of our generosity: for instance, the “second-hand” trauma that Poles can experience by hosting people afflicted by the war. One post, quoting a famous line from Wisława Szymborska’s poem, “We know ourselves only to the extent we have been tested,” posited that we think through our decision to open our doors to the refugees, and analyze our resources – financial and mental.

In other words: self-reflect on what you might be able to actually handle and be mindful of the fact you might be volunteering yourself and your family for difficulties. While this is a very thorough and well-meaning approach, had it not been for the (reckless?) generosity of thousands of Polish families, Ukrainian mothers, children and elderly would be largely camping out on the streets, as state support in the area of long-term accommodation is still in its infancy. What’s more, most refugees opt for big cities and there are increasing problems with finding places for rent. Ultimately, the forms of help are many, and everyone can choose their own, even if it is refraining from spreading misinformation and hate-mongering. Malcontents aside, many Poles have confessed that seeing the grass-roots initiatives for the benefit of Ukrainians, they’re finally proud to be Polish.

To suggest that there’s an absence of fear or worry would be dishonest. We are concerned and very much paying attention to the present; it’s difficult to think much about the future or justify spending money on trifles. But like with most things in our house, we’re guided by dialogue, talking with each other about how we feel and what we might be able to do. And instead of amplifying fears, we draw strength from Joanna Warren’s generous insight, which – although aimed at the art of translation – could very well be describing our current crises:

What translation can do for us, and what we so desperately need at this juncture in human history, is to radically increase our empathic capacities; to learn, or perhaps relearn, how to listen – to people of all linguistic traditions and hopefully, some day, to beings who don’t “speak” at all. As our empathy expands, so do the confines of our own egos. As our compassion grows, we become infinite.

Right now, many people in many countries are translating words into actions. The Russian President’s words have been translated into an unprovoked military invasion, destruction, demonstrable lies, death, and wanton cruelty; in response, much of the international community is translating empathy.

††† ††† †††

Katarzyna Szuster-Tardi is a translator. Recent translations include the books To Feed the Stone by Bronka Nowicka (Dalkey Archive Press, 2021); Polish Literature and Genocide by Arkadiusz Morawiec (Routledge, 2022); and the chapbook Codex of the Insane: Body and Related Matters by Bronka Nowicka (Toad Press/Veliz Books, 2021). An excerpt of Don Mee Choi’s work translated into Polish was included in the recently published book Odmiany Łapania Tchu (Variants of Catching Breath) published by Dom Literatury in Łódź. She earned her M.A. in English studies from the University of Łódź, Poland. Recent translations have appeared or are forthcoming in Conjunctions, Czas Kultury, Hunger Mountain Review, Denver Quarterly, The Sextant Review, Washington Square, Michigan Quarterly Review, Tripwire, and LIT.

Mark Tardi is a writer, translator, and lecturer on faculty at the University of Łódź. He is a recipient of a 2022 NEA Fellowship in Translation and the author of three books, most recently, The Circus of Trust (Dalkey Archive, 2017). He curated the recently completed Variants of Catching Breath project, which brought five American writers to Poland for a series of events – Don Mee Choi, E. Tracy Grinnell, Nathalie Handal, Sarah Mangold, and Tyrone Williams – and culminated in the publication of the book Odmiany Łapania Tchu (Dom Literatury, 2022) featuring excerpts of their work in Polish translation. Recent writing and translations have appeared in Poetry Northwest, Lunch Ticket, The Scores, Denver Quarterly, The Millions, Circumference, La Piccioletta Barca, Berlin Quarterly, and in Italian translation, Rossocorpolingua. His translations of The Squatters’ Gift by Robert Rybicki (Dalkey Archive) and Faith in Strangers by Katarzyna Szaulińska (Toad Press/Veliz Books) were published in 2021.

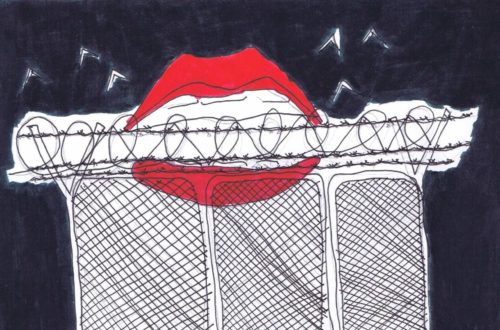

Oksana Drachkovska was born in Chernivtsi (Ukraine) in 1987. I grew up in Chernivtsi and moved on to study at an art college located in the Carpathians then I moved to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Lviv, where I’ve been living for the past 12 years. I studied in Lviv National Academy of arts (Painting) There are quite a few things that inspire me (some of them might be a little weird). Trees, the sea and the ocean, as well as birds and clouds. And, of course, I love to observe people, they inspire me quite a bit. Every person I meet gives me a better understanding of myself. I like to play with metaphors. I’m one of those people who find it easier to think on paper

Visit Oksana Drachkovska and see her artwork at Instagram and Behance.

And to support Ukraine: Come Back Alive