Woman, 46

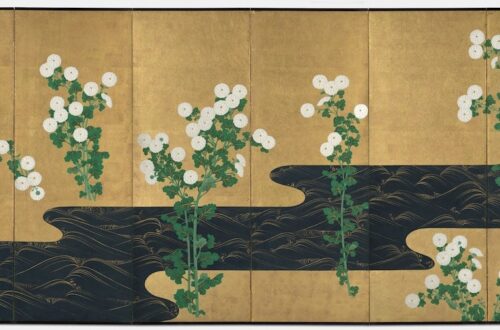

"Listen" collage by Tiffany Dugan

by Wendy BooydeGraaff

The morning of my thirty-ninth birthday, my fingertips looked hazy, as if I suddenly needed glasses. When I took off my socks (I always slept in socks, even in summer) my toes, too, were strangely abnormal. Transparent. The toes came back for a few hours on my fortieth birthday, but the day after the obligatory party, other parts of me began to fade in a spotty sort of way. My tailbone, then my left shoulder, the side I slept on. Strange, the sensation of being on the shoulder but appearing to hover above the bed. I started sleeping on my right side, which stayed solid until I turned forty-two, at which point I had no visible shoulders, and had to sleep on my back, which meant I did not sleep much at all. My chin disappeared, then my left ear lobe and my uvula. People started talking through me, and that’s when I realized my voice was going, too, like the static on my old vintage radio, fading in and out. My husband pieced together what I said, through gesture, mind-reading, or general what-the-fuckishness.

“Can’t you see what’s going on?” I asked Alek.

“You look good to me, hon,” he said, sliding his hands from my invisible shoulders down to my visible elbows. My right inner wrist had disappeared. Still, the familiar pulse of adrenaline rushed through my veins when he touched me.

“You don’t see this?” I asked. I lifted my shirt. Bellybutton, gone. Lower left rib, gone. When I say gone, I mean visually gone. I patted my stomach—by touch, it existed. Physically my tummy muscles tied my ribs to my pelvis. I prodded my lower rib. No holes, just visual glitches.

I wasn’t disappearing. I was going invisible.

“Ha,” he said with a lilting tone of sexual innuendo. “After dinner, I’m all yours.” I followed his gaze to my breasts. Of course, completely visible.

“Look at this.” I grabbed my nose. The nostrils were invisible but the bridge of it still crooked down.

“No need for a nose job!” He tweaked the knobby cartilage and walked past me to the fridge. He opened the door and perused for something to eat.

“You can’t see this?” I said. Alek’s head was in the fridge, which even under non-invisible circumstances would make it extremely difficult for him to hear me.

He must have pieced me together from the last time he actually looked at me, all of me. His gaze now floated over the bits that didn’t match up any more, the way a careless museum guard might fail to notice a forgery. He had a memory picture of me—so did I! My ultimate self!—from year thirty-two, my year of greatest visibility, the year I glowed. My career had hit its stride. I was on track to head the marketing department, whispers floated of a VP promotion, and I had a call from the local community college asking me to adjunct for a business class. Big plans. Until a refractory postpartum infection forced me to take leave.

Jared whizzed by, his head now in the fridge alongside Alek’s, his hair the same shade of dark brown, without Alek’s streaked gray. The unmistakable suction sound of the fridge door opening must have lured him from his Lego construction of world-famous towers.

“What do you think, Bud?” Alek said. “Tacos?”

I was hungry, too. “Mmmm, tacos,” I said. I had shopped and stocked the fridge with the ingredients, washed and chopped the cilantro, the jalapeños—and yes, invisible finger pads still sting from capsaicin. “Sounds perfect. Make me one?”

Just today, my chest wall went invisible. If I ate a taco, would I see it pass down my invisible esophagus? Would I see it showered with digestive enzymes, churn in my invisible stomach?

Jared and Alek took their tacos to the couch. Jared tripped on my toe and dropped one of his tacos on the floor.

“Five second rule!” Alek shouted, and Jared speed-scooped up his taco.

I raised my invisible shoulders. “What the hell?” I said with my invisible voice.

The tortillas were gone. The counter was strewn with taco detritus. I scraped up avocado, cheese, tomato, cilantro, diced onion, and a stray black bean with a spoon. I chewed. My teeth were not invisible. Not that it mattered; no one was looking.

Strangely, my tears were the last to go. Tears, of course, had always been transparent and easily ignored. For them to go invisible merely marked the culmination of something that had been avoided for years, along with the pats on the back, the dismissive statements accumulating like dandelions on the front lawn: “Buck up” and “A good massage do the trick.”

We went to the movies, the three of us. The Avengers. I went to the bathroom after, and when I came out, Alek and Jared were not standing in the popcorn studded hallway, waiting. I texted and phoned. No response. Our car was gone from the lot. I walked the two point one miles home in my stiff shoes and my too-thin coat. Car headlights whizzed by. Would anyone notice if I stepped in their path?

The front door was locked. The spare key lay hidden under the fake rock. I sobbed, this last indignity too much, rooting around in the front garden for that stupid fake rock. I swiped at my face. Snot and tears dripped viscously from the back of my hand. I felt them but could not see anything. My bodily secretions, now invisible.

Evidence of existence persisted in the mirror: streaked mascara tracking down the slopes of invisible cheekbones, red rims of increased blood flow around my eyes. I cry, therefore I am. But what is the point of crying? Is crying a cure for anything? Or does it only inspire more crying? Who the hell knows? I stopped wearing makeup.

By forty-six, I was entirely invisible.

You might think this is fun, to spy on people, to slink around knowing what they say when you aren’t around, as if wearing a magical cloak in a fairy tale. But there’s no casting off the cloak, no one to hear what you’ve found out, no one with whom to gossip.

At night, I wandered the house, picking up discarded hoodies, wiping crumbs off the counter. I passed Jared’s Lego towers of the world, now fully constructed: Tokyo Skytree, Eiffel Tower, Anaconda Smelter Stack, all neighbored side-by-side on the same plat of green flat plastic. I snapped off the tip of the CN Tower, and hid the spike under the cushion of my make-up table stool.

You might think you’re destined for a happy ending. I thought the same. I was on my way to being someone in this world.

I was there and then I wasn’t.

Alek looked, and looked, and then he didn’t. Jared searched longer. Then he hit puberty. Poof! He was lost in the way of men who insist on visibility as a criterion for personhood. To everyone else, I merely disappeared. I stamped my way through the dance of life and ended up an eternal invisible flame.

You began sitting at my make-up table, using my soft pink gloss, admiring yourself in my lighted mirror.

Maybe I wished this on myself, my own self-curse of self-determinism. There were times I wished I was invisible, unencumbered by others’ needs and interruptions. What am I thinking? I shake off this idea, that women must be the cause of their own ailments.

I still need the door to be open before I can pass through, require food to ingest in order to live. Invisible doesn’t mean airless, floating, fitting through cracks. I sleep on the spare bed with covers humped over my invisible frame, or, more often, on the bedside floor like a protective cat beside you, socks on, as always, though you don’t notice. You wouldn’t.

After years of night-time walking by the Lego towers, first set on the corner table, then moved to the mantle like art, I decide to resurrect the tip of the CN Tower. I extract the spike from under the seat cushion, rinse it off under the tap. I bring it downstairs to return it to where it belongs. But there’s already a new tip on the CN Tower.

I snap it off, replace it with the original, bring the proxy up to Jared’s room. When he sleeps, his younger face emerges from the mustache stubble, the strong teen jaw replaced by parted lips, ruddy cheek mushed against the pillow. I set the Lego piece beside him, on his nightstand, on top of his phone.

I am here, right here. I am the naked breeze when the window isn’t open, the heat when the furnace isn’t running. I am the lock of hair that shifts out of your eye when your hands are occupied. I am the plucked note your fingers can’t reach when you play my piano. I am the shiver beside you when you thought you were alone.

I watch the way you fawn over Alek as he does the dishes, as he brings his aging mother flowers on Mother’s Day, as he pats his equal-height son on the shoulder. You think he is the ideal man. You imagine he’ll see you and all the beauty you contain forever.

But I am the one whispering in his ear, reminding him his mother likes fuchsia blooms best, that food tastes best on sparkling clean dishes. I am the one flitting your frilled sleeve so he’ll compliment your manicure. I am the one hovering by your shoulder adding salt while you hyperbolically bat your eyelashes over the pasta carbonara and crisp mesclun he prepares for you.

You think to yourself you will never become invisible, it’s not true what happened to me, his gaze is yours forever.

How old are you? Thirty-eight?

I whisper you are important, you are beautiful, no matter which parts become invisible first. Purpose resides within. And should you need it, I will be the insistent mosquito buzzing in your ear, forcing you to slap yourself back to reality before it’s too late.

Wendy BooydeGraaff’s short fiction has been included in Ninth Letter online, Harpur Palate, Thirteen Bridges, Maudlin House, and elsewhere. She is the author of Salad Pie (Chicago Review Press/Ripple Grove Press), a children’s picture book, and her middle grade short story “The Michigan Triangle” is anthologized in The Haunted States of America (Henry Holt/Godwin Books).

Tiffany Dugan makes art and writes in her home studio in Inwood, NYC. She has exhibited in 30+ solo and group shows and is in collections throughout the US and Europe. She received the Sarah Lawrence College Gurfein Fellowship in Creative NonFiction (2019) and wrote a memoir “Love and Art” about growing up the creative daughter of an abstract painter and the art legacy she inherited after he died. Tiffany went to Sarah Lawrence College (BA) and is a proud Milano, The New School alumna (MS). For more of her art, visit W: tiffanydugan.com IG: @tiffany.dugan